From the Editors: This is the final winning essay from our 2025 Personal Essay Contest. Thanks to everyone who submitted their essays. Tomorrow, it’s back to the local news.

By Bill Phillips

I wasn’t raised particularly religious as a youngster 70 or so years ago. I remember my maternal grandparents were members of the Rock Island Baptist Church in Port Arthur, Texas and my maternal grandfather, who was born in 1900, was a deacon of that church. He was very fervent. I was always amazed at his sonorous voice and more amazed later in life to learn that he had been a businessman with only a fourth-grade education.

I remember every summer or every other summer visiting those maternal grandparents and being made to go to church. It was a big production—up early, find church clothes, eat a good Texas breakfast (usually of grits, eggs, sweet and creamed coffee, thick bacon and homemade biscuits), then pile into my grandparents’ old Chevy and rush to church.

My maternal grandmother, whom we called Grandma, guided us inside the church while Granddad took his place among the church leaders. Once inside, seated in the regular pews, I remember fidgeting as sweat oozed down the back of my shirt and muttering “Too long! Too hot!” It was only around nine in the morning, but the Texas Gulf summer heat and humidity were already ridiculous.

I really don’t remember paying much attention in church proper, but I do remember Sunday school. There seemed to be a lot of activities to do and many stories about simple lessons on kindness to others. I also remember the feeling of freedom as we heard the last gospel hymn sung, and my brother and I ran out the front of the church to play loudly—very loudly—with the other kids.

My paternal grandparents were members of an African Methodist Episcopal church in Waco, Texas. I think it was St. Lukes’s, a very old, black church in Waco.

My paternal grandmother, who was born in 1898, was a teacher with a doctorate in education. She went to church every Sunday, but my college-educated paternal grandfather, a businessman, didn’t. In fact, I can’t ever remember him coming with us to church during those summer visits. He was more interested in his “church” of watching the baseball games on TV, tasting his cigars and occasionally sipping a honey-gold liquid he called “Kentucky tea,” from a small mason jar.

My paternal grandmother, whom we called “Gran,” didn’t insist that her grandchildren go to church every Sunday like my other grandparents did. Every once in a while, she would ask us to go, and we would, and she would show us off to her friends.

She was very joyful when going to church. I vividly remember the rather large-brimmed and colorful hats she wore then in all shades—vermillion, lavender and saffron. At the crown of each hat there was always some brilliant plumage that, in hindsight, may have been representative of a kind of communal consciousness memory of her mixed, Kiowa ancestry. She never spoke of the reason for the vibrant multi-colored feathers. Perhaps she just liked them.

The visits to her church were more pleasant for my brother and me, which I attribute mostly to the fact we were not “made” to go. She sweetened the deal by giving us both a half stick of Wrigley’s Double Mint gum each time we went. Hmm, that was so good! Our mouths watered as soon as we saw her reach into her large fancy church bag because we knew what was coming. I think it was because of this that my brother and I actually kept quiet and didn’t squirm.

Growing up, my parents primarily left it to my mother to dabble in religion and churches for us. We visited several churches as preteens and early teens, but we never had a regular church. Both my Mom and Dad were working: Dad as a professor and Mom doing classwork at medical school at night while holding down a job as a biochemist at a local pharmaceutical company during the day (and running our home).

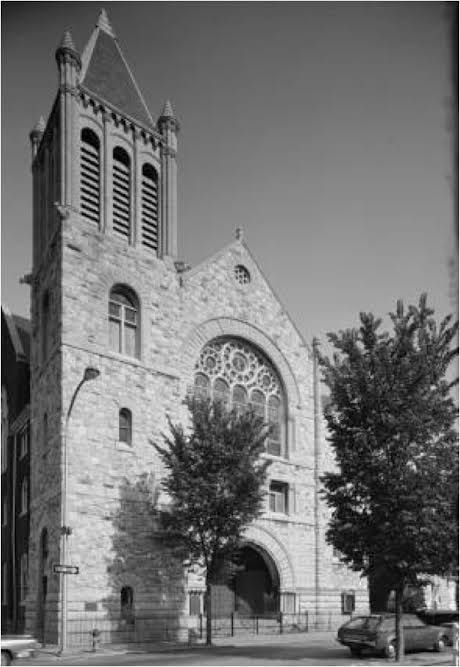

It wasn’t until I went to college and began taking some introductory courses in philosophy and theology that I actually got curious about religion, God, spirituality and such things. After a particularly moving sermon at Andrew Rankin Chapel one Sunday morning at Howard University during my freshman year, I briefly considered becoming a minister and majoring in religion. Then I changed my mind and decided to become a historian, earning a law degree and eventually winding up as a career federal employee, eventually working at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

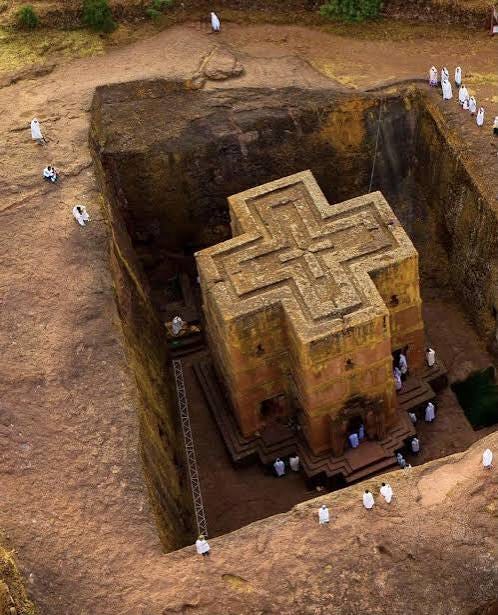

My great spiritual “doubt” has been a foundation of my lifelong curiosity and investigation into religion and spirituality. During one of those later years in college, my interest in religion peaked so highly I started a history research project on the Temples of Lalibela, a series of eleven underground Ethiopian Orthodox Christian churches dating from the 13th century. Those “holes in the ground” were ancient, historic and holy worship places: churches!

While I was studying the Temples of Lalibela, I also was trying to learn Amharic, one of several official languages of Ethiopia. Eventually, I gave up that project and went on to study American and medieval history. Over time, my interest in religion became, let’s just say, less present.

As I grew older, my curiosity about religion re-emerged sharper, as probably happens with others. It dawned on me that the churches I experienced as a black child were powerful motivators and instigators in how I felt (and still feel) about the world and how I fit into it and how I might contribute to it. My early association with places of worship centered around smells, luminous colors, sounds, feelings, energy, mystery and historicity rather than doctrine. Of course there is a place for doctrine in religion, but for me a church is something different—and perhaps more—than doctrine.

A church can be a building, a quiet corner of a city, a hiking trail in the Sierras, or a lemon orchard like the one off Cherry Ridge Road in Sebastopol. It can even be a national monument. Sometimes, when I visit the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., I get that eerie, reverent, church-energy feeling as I stand there and look at Lincoln’s craggy, chiseled face.

The churches I mentioned—the Rock Island Baptist Church in Port Arthur, Texas; St. Luke’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Waco, Texas; and the Andrew Rankin Chapel in Washington, D.C.—share the same smells, vibrancy, energy, deep mystery and joy despite their doctrinal differences. And occasionally, even today, thousands of miles aways from my early church experiences, I will get a strange, ethereal whiff of double mint gum when I visit a different church now.

I suspect that “listening with intention” has helped me see churches all around me. I learned from Gran that church was something penetrating and mysterious, buried beneath the accoutrements of daily life, that it was a place where the pulse of the Divine transcends the mundane world of doctrine to touch the universal world of love, curiosity, kindness, friends, relatives, and perhaps acceptance even of those we may not like. Church is all around us, and we are constantly “in” church. All we need to do to find that church is listen.

Bill Phillips lives in Sebastopol with his wife, Linda, and their dog, Cleopatra. The three of them are members of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Sebastopol.

What a beautiful essay. A wonderful reminder that everything is sacred; we just have to pay attention.

Wonderful essay. Really wonderful.