Capturing the spirit of design

Sebastopol resident Bob Beauchamp spent countless days at a local coffee shop composing a guide to nature-based architecture

If the maxim that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture” is true, then what is writing about architecture like?

That question would be better posed to Robert O. (Bob) Beauchamp, a Sebastopol resident who has condensed what he’s learned about “architectural functionalism” throughout his career as an architect into a single textbook.

“I wasn't a very good writer, but I didn’t know that,” Beauchamp recalls of when he first sat down to work on the book. “I watched 200 lectures about writing skills, and I kept writing.”

And write he did, holing up not quite in solitude, but at Retrograde Coffee Roasters several mornings a week for the better part of a decade.

Beauchamp now hopes that his book can give students today a structure they can use to develop and design buildings of their own more effectively.

“When I was a student, we were being taught to design similar to throwing you in the deep end of a pool and learning how to swim,” Beauchamp said. “You just swam or sank. It was an awful way to design.”

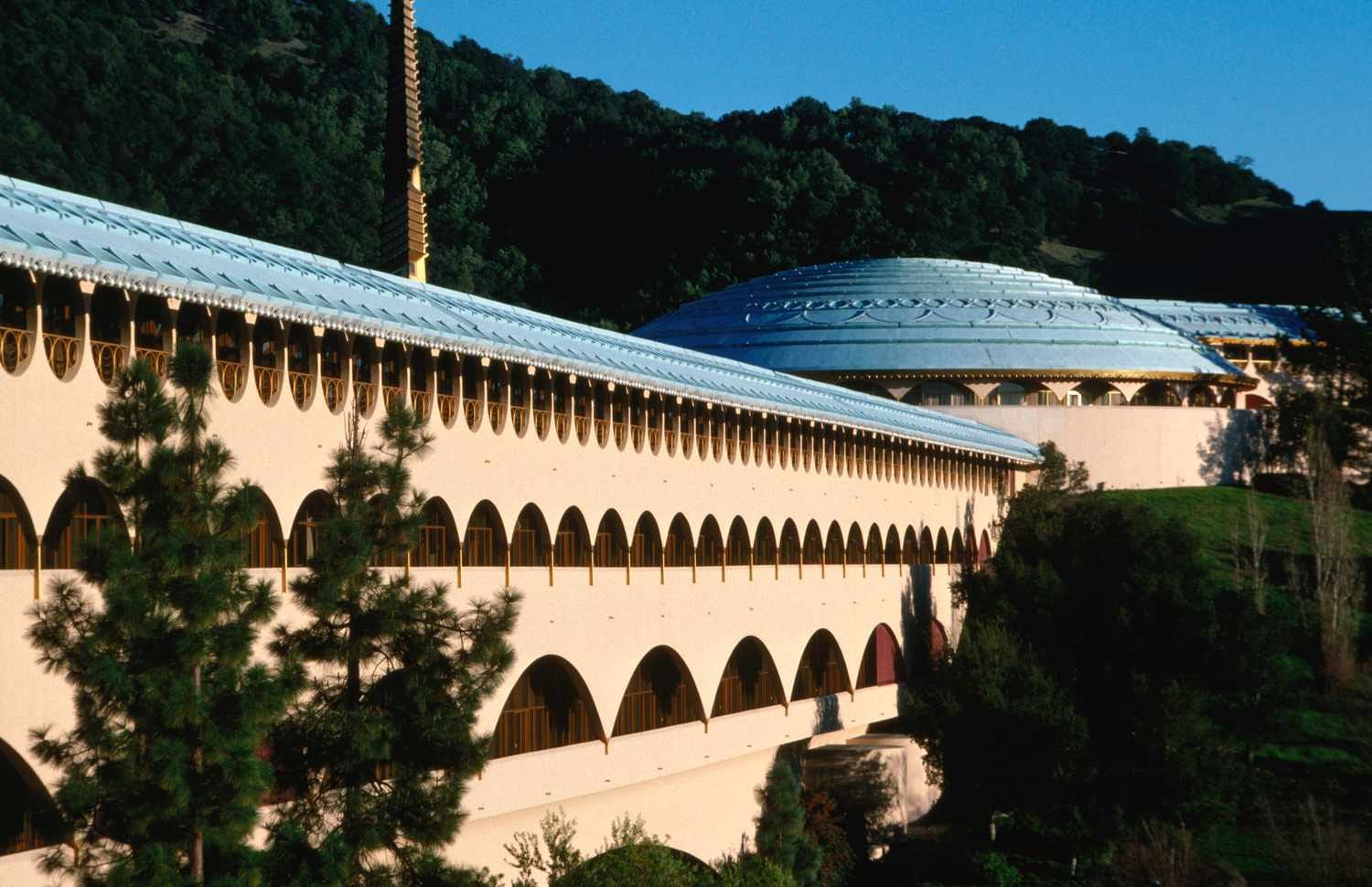

After graduating college, Beauchamp knocked on famed architect John Lautner’s door and got a job working in his office, which was really just a two-car garage.

Beauchamp worked for multiple nature-based architects throughout the 1950s and 60s, including Frank Gehry and Cesar Pelli, before teaching architecture at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. As a professor, he often felt that by talking about the specifics of architecture he was taking his students out of their creative state.

“I realized that I was going to have to tell my students that they’re going to have to put away their all their personal development and architectural skill development,” Beauchamp recalls. “Put it down on a shelf somewhere, and open your mind.”

While Frank Lloyd Wright, the pioneer of the “organic” tradition that Beauchamp had structured his career around, designed hundreds of buildings, he was not one to document his ideas. So, as a young man, Beauchamp travelled around the country to visit many of Wright’s works.

“Contrary to what our religions often tell us, we’re not superior to nature,” Beauchamp said. “It’s quite okay for us to take a back seat, to humble ourselves to nature’s supremacy, and to use it as an inspiration. You know, we’re a part of nature inherently.”

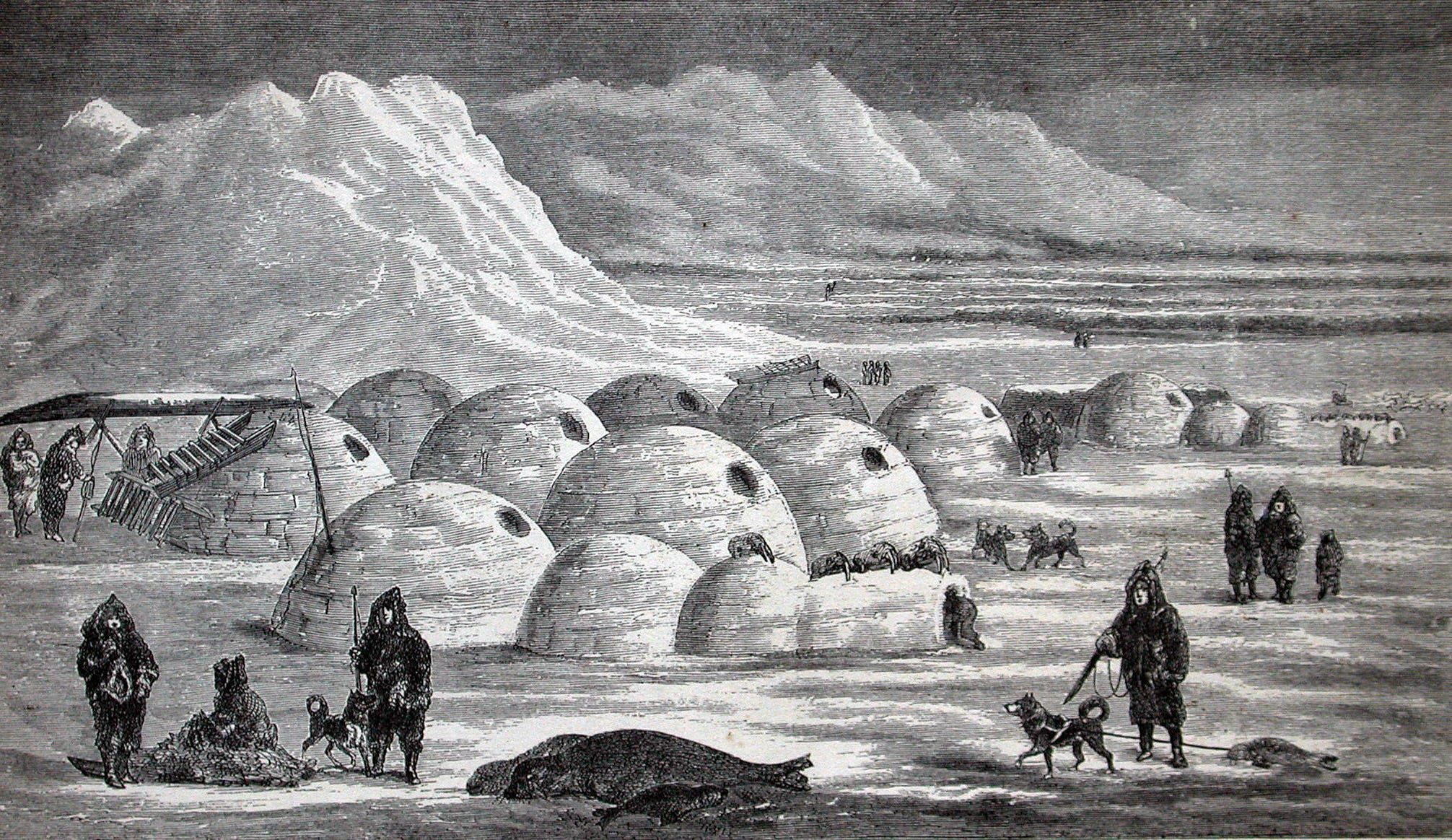

Nature, Beauchamp says, is beautiful because it has integrity—it is honest and true to form. An igloo, moreover, is a great structure because its shape is determined by its function, which is to isolate from the cold and allow people to enter.

“Nobody says, ‘I don’t like sunsets or waterfalls,’” Beauchamp said. “And that’s an important aesthetic position in the book. It doesn’t matter what you think you know if the building is right.”

But how does one know whether what they are making is “organic” or “natural” or “right”?

Mystical questions such as these have been asked by artists since time immemorial. The hard part is articulating their answers in a way that a less experienced but thoughtful person can understand.

To do this, Beauchamp employs multiple disciplines. The first chapter of Beauchamp’s book, which is titled, “Personal Factors that Influence the Designer’s Mind,” discusses how qualities of mind such as IQ and the ego can all change the temperament and product of an artist.

So Beauchamp’s book begins:

“The factors that exert meaningful influence on successful architectural design are broad, varied and many. They can range from the minuscule and mundane to some of the deepest functions of the universe, from the most profound theories that connect us to all of the natural order of things. Combined they become the full range of realistic criteria that can directly determine a buildings true greatness. Such a list ought realistically to begin with those influences that lurk within the designer’s “interior,” the darker recesses within their ever-complex mind. This area can be notably vast and impactful yet is one that is almost entirely ignored by the profession. It can encompass several significant areas of consideration, from the designer’s childhood, their cultural influences, social class, socio/economy, history of victimization by oppression, etc. It can, in fact, often be the primary source of their incessantly conflicted reasoning that initiates a design trajectory that cannot escape mediocrity, time after time.”

Other sections of the book, which are titled, “Form and Function as Yin and Yang,” “The Zen of User Process” and “Imagination, Tenacity, Courage and Resolve” also employ this holistic approach.

Interspersed between these discussions are practical knowledge—lessons on geometrics, form-making, construction logistics and more.

At its best, says Beauchamp, great architecture can “exude feelings of exhilaration.”

“Everyone all over the world knows San Francisco for its life,” he said. “A building can do the same thing. It can have a vitality. It’s not easy to explain, and I do my best.”

While other art forms like painting or writing may need a curator or publisher in order to be realized in the world, architecture needs a whole lot of money and labor to see through a vision. Beauchamp recalls exhaustion at designing buildings only to have city councils act with little urgency or clients push their own ideas.

“They don’t know shit when you're working on something,” he said. “It’s a nasty kind of a circumstance.”

Thankfully, Beauchamp was able to design his own residence in Sebastopol that he now spends his golden years living in.

Two decades ago, when Beauchamp built the house, it only needed to have around 60 “GreenPoints,” as determined by a measuring system that Sebastopol used.

The home would be awarded 133 GreenPoints by the city, according to Beauchamp’s wife, Tasha. Beauchamp used metal scraps as flower pots and a steel roof. He created an effective rainwater collection system and included plenty of windows in both the main house and the garage to creatively bring sunlight into the space.

Beauchamp’s home also uses a wood stove to heat the house and has insulation which keeps the air naturally cool in the summertime.

Instead of buying furniture to go with the space, Beauchamp had most of the tables and seating areas already built into the structure. This includes a long couch which spans the entirety of the living room, with different places to sit if you are socializing, reading or watching TV.

“We use it every day, in some part or another,” Beauchamp said. “It becomes part of the house itself.”

Beauchamp’s book can be purchased here on Amazon.

How about suggesting that we can purchase the book at Copperfields? Go Local!

Well done, Bob.