Ever wonder how the county chooses which homeless people to house?

PART 1: The team from HomeFirst, which handles Coordinated Entry for the county, came before the Sebastopol City Council to explain how homeless people are chosen for permanent supportive housing

This is Part 1 of a two-part article on the Coordinated Entry System, which is the system that matches homeless individuals with housing. Part 1 will explain how the Coordinated Entry System works, and Part 2 will deal with efforts to make it work better for Sebastopol in the future.

Ever wonder how the county decides which of its 1,952 homeless people it will place in “permanent supportive housing,” such as Elderberry Commons or Gravenstein Commons, which is currently under construction in north Sebastopol?

How, for example, does a homeless housing complex, such as Elderberry Commons, end up with a combustible mix of disabled seniors, active meth and fentanyl addicts, people in recovery, parents with children and the seriously mentally ill—all under one roof like some big, unhappy family that requires regular visits from the local police.

How does that happen? More to the point, how can the city of Sebastopol stop it from happening again at its newest Project HomeKey site, Gravenstein Commons?

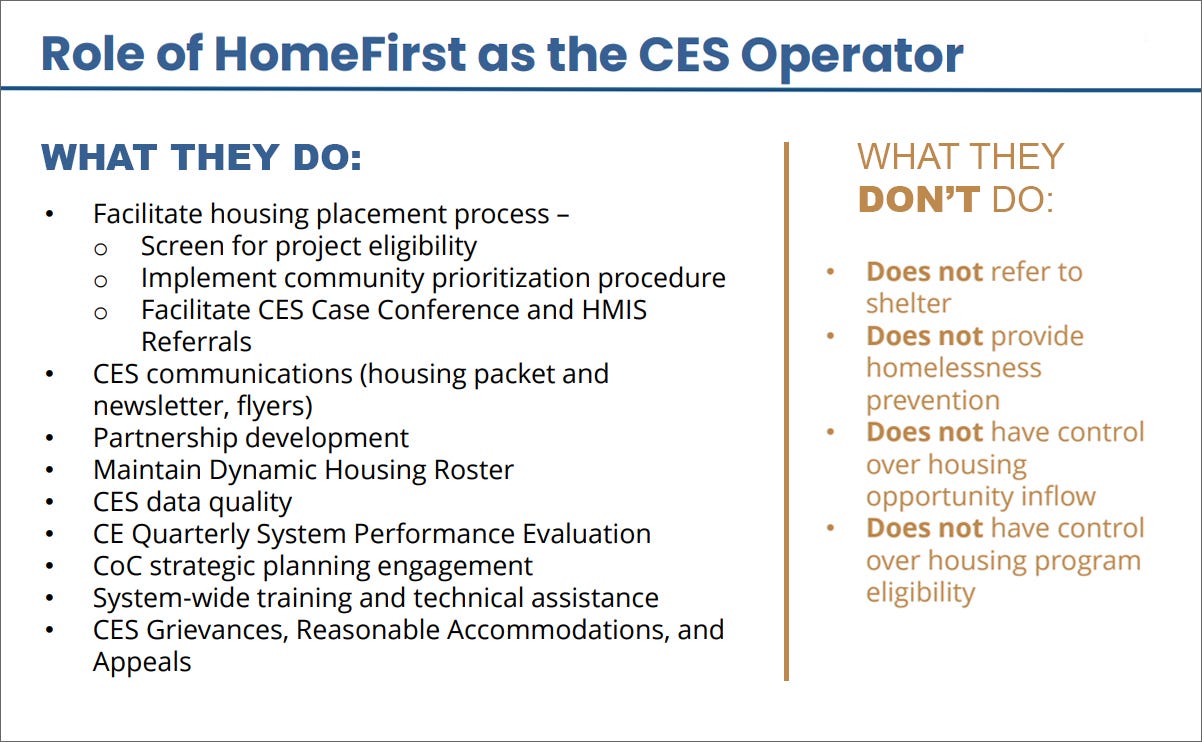

To answer that question, Mayor Zollman invited representatives from HomeFirst, the county’s Coordinated Entry operator, to give a presentation to the council about the Coordinated Entry system, which, according to a county website, “is designed to match people experiencing homelessness to available supportive housing programs.”

What is Coordinated Entry and how does it work?

Hunter Scott, the vice president for HomeFirst in Sonoma County, kicked off the presentation by introducing HomeFirst, which took over the management of the county’s Coordinated Entry System from Catholic Charities in 2022.

“HomeFirst is a 45-year-old organization with the goal of ending homelessness,” he said. “We’ve operated the Coordinated Entry System in Sonoma County for the last three years. During that time, about 2,500 people have left the system into permanent housing, and about 3,600 people are served by the system each year. I just want to thank the city of Sebastopol because you’ve provided incredible contributions towards addressing homelessness over the years with various supportive housing sites and your outreach team. So thank you for that.”

He also noted that Sebastopol’s experience has not been “entirely positive for everybody involved, and so there’s understandable fear about how Gravenstein Commons is going to work. Our goal today is to talk about our role in filling these types of sites.”

He then turned the presentation over to Kaitlin Johnson-Carney, director of Coordinated Entry for HomeFirst, to explain how the Coordinated Entry System works.

“Coordinated Entry System’s central role is to facilitate housing placement referrals. Everything we do is centered around that core role.” Below is a list of the things HomeFirst does and does not do. (CES stands for Coordinated Entry System and CE stands for Coordinated Entry):

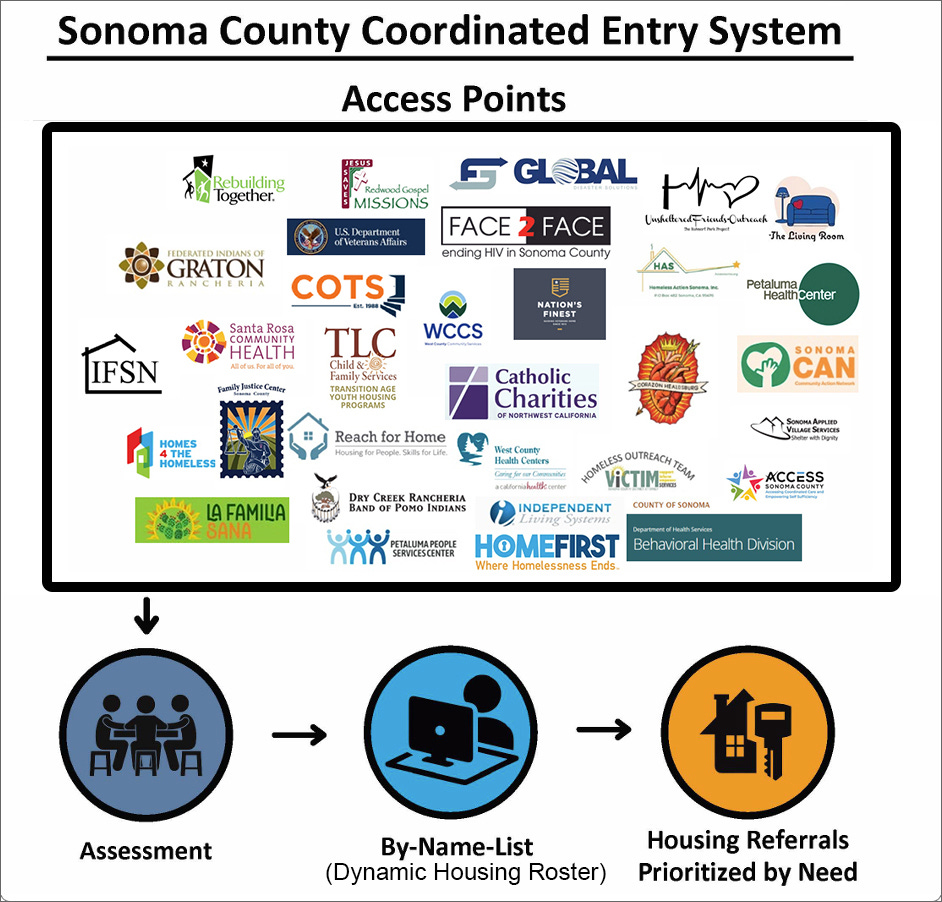

Carney began her presentation by introducing the basic flow of the Coordinated Entry System: “People experiencing homelessness are assessed by a community-based organization. That assessment places them on a list [called the Dynamic Housing Roster], then referrals are made from that list into housing depending on the specific eligibility of that housing project.”

In the Coordinated Entry System, the community-based organizations that deal with the homeless face-to-face are known as “Access Points.”

Carney noted that HomeFirst had greatly increased the number of community organizations (Access Points) involved in the system—up from 12 three years ago to 31 today. HomeFirst has also increased the number of trainings available for these providers from one per quarter to 23.

“The Access Point role in the Coordinated Entry System is to assess people [i.e., the homeless] and then continue to contact and keep those people active,” Carney said, by which she means regularly updated in the Coordinated Entry database, which is called the HMIS (Homeless Management Information System).

If a homeless individual’s HMIS record isn’t updated within 90 days, their record becomes inactive—at which point that individual is no longer in the running when housing becomes available. Their name is removed from the system after a year of no contact.

Assessing Vulnerability

The Coordinated Entry System prioritizes those who are most in need of assistance, based on a vulnerability scale.

HomeFirst depends on its community partners to assess homeless individuals to determine their level of vulnerability. Until recently, this was done through an assessment known as the VI-SPDAT (Vulnerability Index – Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool).

When we reached out to Carney after the council meeting, she said this assessment has now changed.

“It was a very lengthy assessment,” Carney said, referring to the VI-SPDAT. “It took almost an hour to complete. It was asking about some very severe, traumatizing things that people went through, so it often took even longer than that because now you’re dealing with somebody who’s in a mental health crisis because you just triggered them. So the new assessment, it only takes 15 minutes. It has been designed through a community process with local experts that know how to make something trauma informed. They also wrote the questions so that they’re easily understandable, which was also a problem with the VI-SPDAT. They were written by folks with PhDs who didn’t know how to talk to people experiencing homelessness.”

The new assessment is known as the Combined Primary Assessment. “So far with the new assessment, we’ve got really good feedback about it,” she said.

This assessment looks at a range of issues, but the following items are most important in terms of prioritization:

Length of time someone has been homeless

Risk of death (for example, from a severe health condition)

Risk of victimization

“Institutional utilization” (primarily time in jail, prison or the foster care system).

A person’s responses to this assessment are tabulated, given a vulnerability score, and then they’re added to the Dynamic Housing Roster (which until two weeks ago was called the “By Names List.”) This list ranks the homeless in order of vulnerability.

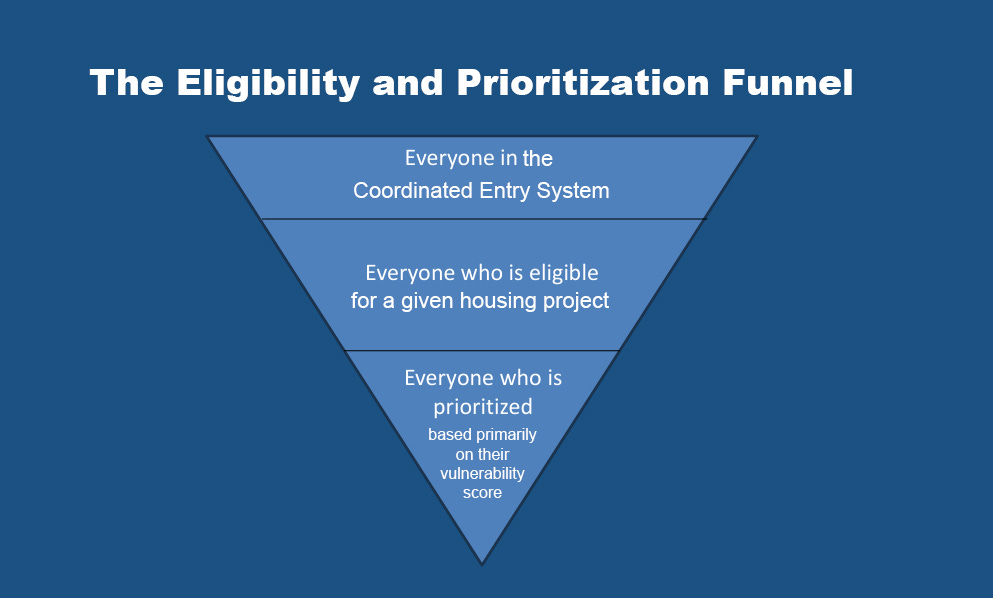

Before launching into the details of how a person gets placed in a particular housing project, Carney made a distinction between prioritization and eligibility.

Prioritization is the ranking of homeless individuals based on their vulnerability as determined by assessments done by the system’s community partners (the nonprofits listed in the graphic at the top of this article.)

Eligibility criteria are used by homeless housing projects to screen applicants. Eligibility is based on three criteria:

Chronic homelessness (This is defined and required by the federal government.)

Property management criteria, such as income levels and background checks

Funding stream requirements. For example, if the funding for a housing project comes from a state grant for “transition-aged youth” (often defined as between age 16 and 24), that would mean that one of their eligibility criteria would be that potential tenants had to be between the ages of 16 and 24.

The question of who is chronically homeless is complex. Here’s the official definition as set by the federal government:

“The definition is either somebody who has been consistently homeless for the past 12 months straight and they have a verified disability, or they have been consistently homeless for the past three years, but with four breaks that add up, so that their time homeless still adds up to at least12 months within those three years,” Carney said.

These breaks are often institutionalizations of various sorts—in jail or in mental hospitals or regular medical hospitals. “If they’re there 90 days, the federal government considers that ‘housed,’” Carney said. “So when that happens, that’s when we use that longer definition to still be able to get those folks into the highest level of services in our community.”

Here’s how questions of eligibility and prioritization play out in action—it’s a funnel:

Just because you make it to the bottom of the funnel doesn’t mean you’ll get housing. There are more extremely vulnerable people in need of housing than there are homes.

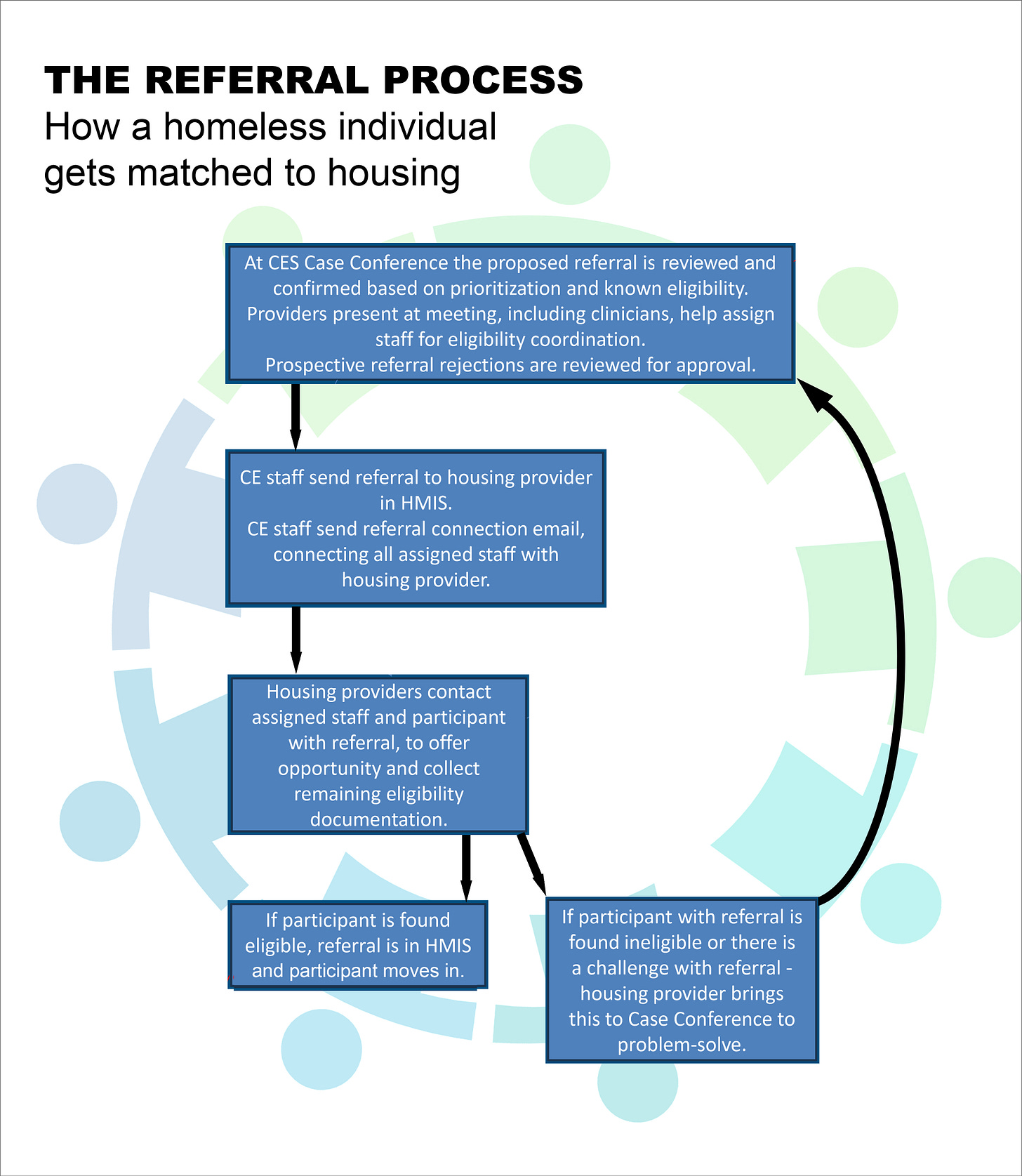

Once a person is assessed, ranked on the basis of their vulnerability, and deemed eligible for particular projects, the referral process starts in earnest.

The Coordinated Entry Case Conference

The next step in the process is the Coordinated Entry Case Conference, a large online meeting which happens in Sonoma County every week on Friday.

“This is where the housing match referrals and housing placement are considered,” Carney said.

“We have upwards of 100 attendees at this meeting,” she said. “We try to have one representative from every organization touching homelessness in Sonoma County. That’s the goal.” This includes folks from nonprofits, like COTS, WCCS, Catholic Charities, as well as homeless outreach and shelter clinicians, community health workers, and county employees working with homelessness and behavioral health.

“Anyone whose role touches people experiencing homelessness,” Carney said. “We’re trying to get them involved in that meeting because those partners know their participants and can speak to their needs.”

HomeFirst facilitates these meetings, in part by pulling together information from all parts of the system.

“So we have what’s called a priority list,” Carney said. “Those are the folks who are next prioritized for housing placements, and we refresh that list every single week to make sure that people who are newly assessed and have high service needs are still at the top of our list,” she said. “We also check for eligibility for the projects we know that are going to be available—whether that’s permanent supportive housing, rapid rehousing, or other housing that’s not Housing First. So we get all of that information together. We also collect contact information [from the homeless] and those people’s preferences so that we’re not sending them to housing that we already know they don’t want, because that doesn’t make sense.”

Interestingly, property managers and developers of homeless housing are not included in this meeting, both because private health information is being shared there and for fear that some information (like a criminal record) would bias them against wanting to rent to that person.

“Those folks [the property developers and managers] do get the information they need,” Carney said. “It’s just not to that granular level.”

Carney said Care Conferences can get heated as advocates plead their clients’ cases.

“We have advocates who absolutely want to get the people they’re working with into housing one way or the other, right?” she said. “Because these are the people they’re working with. They’re right in front of them. They see the need. But then those of us on the other side of the system are trying to make sure that it’s equitable and fair, and that everybody gets a voice, and that we’re considering every issue or option available.”

How many homeless individuals are matched with housing in these meetings?

“It all depends on how many openings in the various programs we have, but it’s anywhere from three or four a week, or when we have a big lease up, it could be 60 people in one meeting.”

Once a decision is made about which homeless individual is going to get housed in a particular place, HomeFirst assigns a staff person to that individual to make sure to seal the deal.

“We assign staff so everyone who has a referral has someone attached to them to help them get to the place and fill out applications,” she said. Sometimes that will be someone from one of the community organizations that has worked with that person before and sometimes it will be county staff.

Part of this job is ensuring that that person has all the paperwork required by the housing application. This is a real issue where the homeless are concerned, because they often lose their possessions (including important paperwork) to police sweeps, rainy weather, or other issues. Depending on the housing project in question, examples of required documentation might include the following: ID card, Social Security card, homelessness verification letters, documentation of disabling condition from a qualified medical provider, or SSI/SSDI letter, veteran status verification, prison release paperwork, and income verification.

Sometimes, a homeless person’s case worker will have already gathered much of that documentation, and sometimes it’s a real scramble.

“Getting everybody document-ready when you have 50 units at once is quite the task,” Carney said, “because that means we’re inundating things like the Social Security office and really monopolizing time at different agencies like that to try to get folks up to speed and ready to move in, especially collecting disability verification that’s required for every unit filled at permanent supportive housing. Disability is a part of that chronic homeless definition, so it’s key to getting that. Some folks, we know that they’re disabled—we can see that in front of us—but they may not have engaged with medical services to get an exact diagnosis. So sometimes it’s helping people through that process, which can take some time as well.”

Despite Sebastopol’s difficulties with its first Project HomeKey project, HomeFirst’s Hunter Scott said most of the permanent supportive housing placements produced by the Coordinated Entry System work out.

“When we look at the data across the entire county at Permanent Supportive Housing sites like this, 92% [of residents] do remain successfully on those sites. We could see maybe an additional few percentage points of folks that aren’t doing well and need additional services, but the point I’m trying to make here is that the model generally does work—but it’s clear that we need targeted, additional resources or alternative resources for a small percentage of people going into these sites.”

Part 2 of this article will deal with Gravenstein Commons in particular and how the city is working with the Department of Health Services and HomeFirst to get a better outcome from the Coordinated Entry System for Sebastopol’s next Project HomeKey site.

Dale and Laura, thank you for your in-depth and comprehensive articles every week. The Sebastopol Times has become a very important read in my weekly awareness of all things important. You are doing a great job!

This seems like a novel, untested system to me. The programs I know that have been successful in housing unhoused people with mental health and/or addiction problems all have the following structure, or steps. First is residential recovery and addiction treatment for 3 months to a year. After that is completed successfully, social workers help individuals clients who've completed their recovery programs successfully apply for and find housing in the different units available for low income folks, including seniors. Seems to me like the Sonoma County program is going in a different direction, rather than following the best practices of successful Bay Area programs for housing unhoused folks. If active drug and alcohol users are included in low income, affordable housing communities, one can expect problems like have been described.

It's like we're missing a big part of the standard approach, here in Sonoma County, like we have untrained do-gooders instead of trained professionals calling the shots, designing the programs. And where are the county social workers? Have those jobs been farmed out to the non-profits the county contracts with? Or have the social worker positions been de-funded over the years?

Thank you.