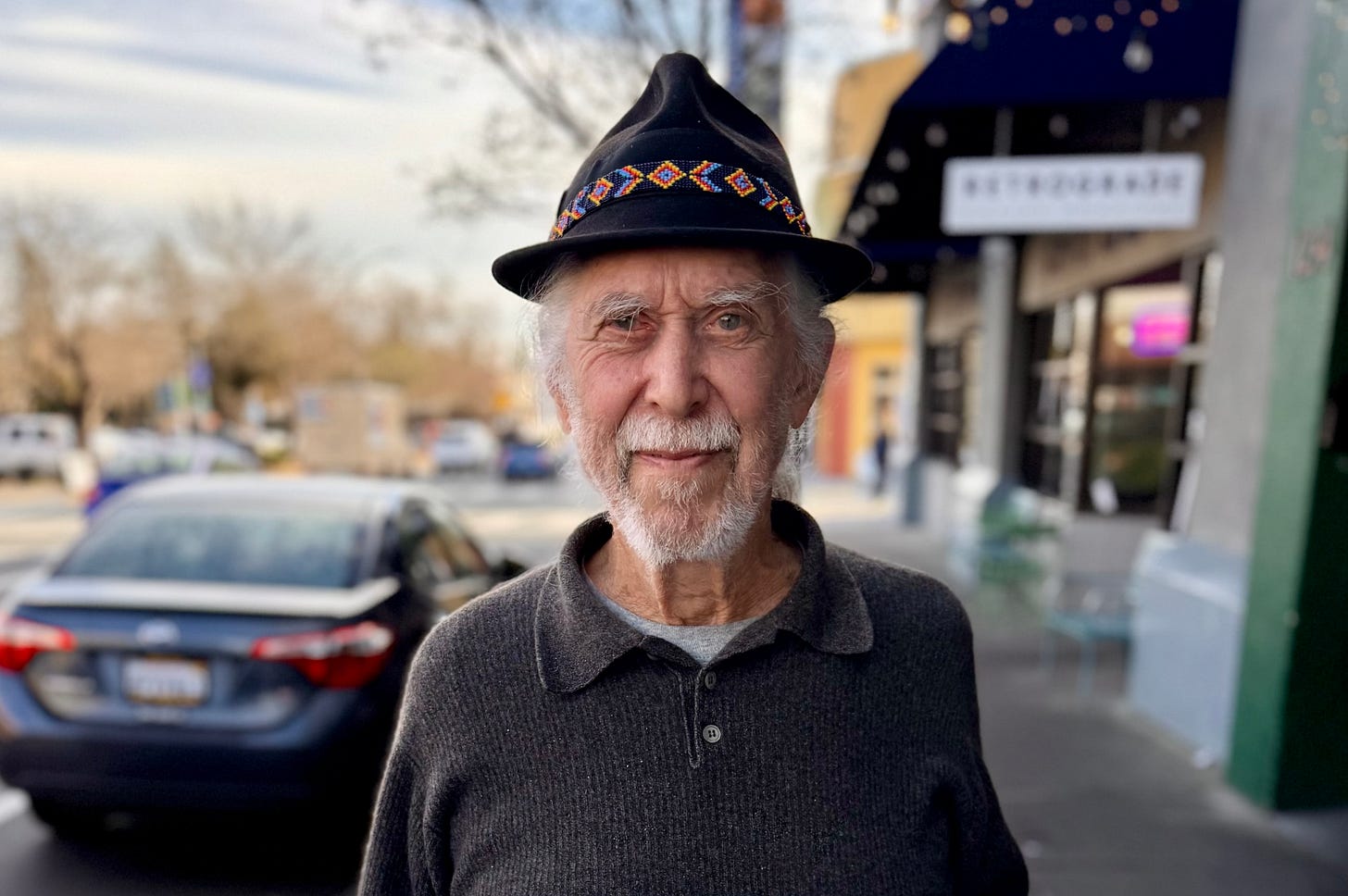

Faces of West County: Barton Stone

Beatnik, peacenik, and meditation master: a local Zen priest's remarkable life

While sitting with Barton in his backyard chatting, he suddenly took a shelled walnut out of his pocket. A large Scrub Jay had landed on a nearby bench and was looking right at Barton.

“He’s an old friend of mine,” Barton tells me.

A moment later, this large wild bird flies over to Barton, plucks the walnut from his outstretched hand and flies off.

A quiet, somewhat remarkable moment in Barton’s day.

Barton lives on a lovely four-acre property between Sebastopol and Occidental together with his partner and love, Constance. Later in the afternoon, he would be hosting an outdoor Zen meditation group here. He’s led that since just after the smoke cleared following the Tubbs Fire.

“We have many permaculture features in the landscape. Eric Ohlsen really influenced us and helped with the work,” Barton said.

I point to a blooming pink plum tree, worried that it’s blooming way too soon. “It always blooms first,” Barton reassures me.

“When someone put in a vineyard on the other side of our property line, we promised to create a natural wildlife sanctuary to accommodate all the wildlife that they were going to displace. The only domesticated animals we have here are bees!”

Barton is a Buddhist priest—something that wouldn’t come as a surprise when you’re in his calm presence.

“Part of the idea here is to live in a space without enemies. I’ve succeeded wildly. I’ve made my peace and come to love both the blackberries and the gophers. I’m still working on my relationship with the Bermuda Grass,” he said,

Barton’s long and colorful life will not be easy to capture in a few lines, but let’s try.

Where and when were you born, Barton?

Kentucky! March 14th, 1938. I’m 86.

My dad was a Protestant minister. We moved around the Bible Belt every two to three years. We lived in Kentucky, Arkansas, Mississippi, Florida, and Alabama. That was the practice of his denomination.

So you’ve been close to a spiritual life from the get go.

Yes.

Did you ever want to become a minister?

No. I didn’t even want to be a Christian!

My dad was too progressive for his congregation. He was favorable to civil rights and other matters, way before the rest of his church.

And your mother and any siblings?

My mother devoted herself to the role of supporting my father and his work, as was the custom at the time. She and my dad were going to be missionaries in Paraguay, but the depression intervened and so they stayed here.

I had an older brother and sister. They’re both gone already.

The gift I got from my mother was that of unconditional love.

That’s a big one and not to be taken for granted.

Oh my, so big.

She understood why I rejected Christianity and pursued a different path, and she supported me in that. My dad didn’t quite get it, but loved me nonetheless. He just didn’t want to talk about politics or religion.

You grew up in the 40s and 50s in the Deep South. You must have seen the evidence of Jim Crow laws all around you.

We sure did. I went to segregated schools until I left school. Part of my awakening was when I spent six weeks at a National Guard boot camp with students from a black college in Alabama. I ended up feeling more in common with them than my white cohorts. We liked the same books and music. That was in ’56, way before the modern civil rights movement.

So you grew up with the “colored only” drinking fountains, restrooms, motels, waiting rooms…

Oh yes.

Where did you go to college and to study what?

Florida State, Tallahassee. I started out in the school of education, wanting to become a teacher, but moved into the philosophy department, being more interested in the meaning of life. The problem was they specialized in dead white guys and not an exploration of religious philosophies.

By 1958, I had enough, and I headed to New York City in search of the dharma.

Perfect timing!

Yes, it was. I went to the Lower East Side near Tomkins Square. I got there a few years before Dylan. I remember the Five Spot Bar, a famous hangout for jazz musicians and poets.

So you were a true beatnik.

I tried to be. I took a vow of poverty on the premise that money was the root of all evil, and I just wanted to be good.

I lived in a $60-a-month apartment with a shared toilet in the hallway. The bathtub, as they were at the turn of the century, was in the kitchen.

How did you support yourself?

I went to a temp job agency from time to time and made just enough money to coast along for a while.

I was studying Buddhism at the time, mostly from the books I got from the used bookstores on 10th Street.

Alan Watts?

Yes, of course. And D.T. Suzuki. And the colonial scholars who brought wisdom back from the East.

Did you ever go to the Far East to study?

Not until years later. I went to Japan to investigate their practice of shrine building. I was really into Japanese building practices, especially their shrines.

Your property here is something of a shrine.

It is.

I worked primarily as a carpenter, and when I retired, I became the caretaker of this property, tending paradise.

California has always been a paradise to me.

So back to New York and your search for the dharma, and maybe Mrs. Right.

Oh, that happened on the walk to Moscow. (Barton says this like all of us have walked to Moscow at some point.)

You walked to Moscow?!?

In 1960 or so, the Cold War was on, and people were terrified of the possibility of nuclear armageddon. There was a committee of Quakers, socialists, and pacifists who were opposed to nuclear weapons, and all war of any sort. When they organized the March to Moscow, it spoke to me.

How long did that take?

Eleven months. I did the whole thing, leaving from Union Square in San Francisco, across to New York, a flight to London, and then on to Berlin.

We got to Berlin just as the city was being divided, and our progress was stopped. We ended up having to take a bus to the Polish border and continued on from there.

We averaged 15 miles a day. There were 12 of us who set out, and 30 of us who walked into Moscow.

And I did find my first wife on that walk.

I knew it!

My wife-to-be was a student at a Mennonite college in Kansas. She came to walk with us during her spring break and then quit school and joined the walk. That was Martha.

Did you ever get injured or sick in those eleven months?

We were stuck in London for a few days because the French were withdrawing from Algeria at the time and prohibited any sort of political demonstrations for a while. That included us. I came down with a terrible sore throat which was so bad I got myself to a hospital. Two staff people at the hospital came right up to me and asked if I needed help and what they could do for me. No documents, no insurance cards, no money. I get teary-eyed just thinking about that. I want that for everyone.

Were you guys harassed at all for your pacifist stand?

We were constantly met by the same hostile people, both here in the states and over there. We were calling for unilateral disarmament, and many found that very threatening.

That’s not unlike the sign you hold at our local free speech corner here in Sebastopol every Friday at noon.

Which one?

The one that says, “Arms Embargo Now. Everywhere.”

Wow. That’s 65 years since your march that called for the same thing, and you’re still at it with the same plea.

I suppose so.

Did you and Martha have any kids?

Yes, we had two. Amanda, our daughter, who fell in love with a Hawaiian, and ended up moving to Maui. She and her family lost their home in the recent Lahaina fire, but they’re okay. They have two, kids, my grandkids.

Our son, Allen, was a jazz musician who died of leukemia 20 years ago. The same thing that Kate Wolf died from. The sadness was not just his death, surrounded by family and friends, but that at the same time, Israeli jets were bombing Gaza, much like they have done recently. I felt much solidarity with the Palestinians, There was this strange contrast of our Allen’s death which was so peaceful and the violent misery of those being bombed in Gaza.

And after the march to Moscow?

Oh, it’s a long story. Chicago for a while, Green Gulch Farm (a San Francisco Zen facility in Marin), and eventually, when the kids finished high school, Martha and I went our own ways.

How did you get up here to Sonoma County?

I lived in Bolinas for a while, but came up to study at Sonoma State in the Psychology Masters Program. I met Constance in about 1990 when she was a nursing student at the JC.

That’s amazing! That’s exactly when I met her! We were doing pre-requisite classes for nursing at the same time at the JC. She eventually became a midwife.

Yes, she did. And now, she’s another sort of midwife as a death doula. We married about 10 years after meeting at about the time that Gavin Newsom decided it was time to allow gay couples to marry in San Francisco. We thought that was so damned romantic.

Let’s talk about your work as a Buddhist priest and teacher.

Well, I’m very active at the Stone Creek Zendo in Graton. I sit there for an hour and a half at 6:30 am, Monday through Thursday. All are welcomed. No fee, but there’s a donation box.

When do you teach?

You can look at the Stone Creek website to see all sorts of things, including who is teaching on any given Sunday. I am one of five priests, with others in training. In addition to a dharma talk that I give from time to time, I facilitate a grief group these days in addition to an outdoor meditation group.

Where else do you hang out?

Well, I’ve been the chaplain at the Sebastopol Grange for the past five years. That’s been an important place for me.

Barton, how are you coping with the return of a political figure who is so distressing to many of us?

I haven’t made peace with it. It actually causes me to weep on most days.

Hey, did we talk about The Voyage of Everyman?

No. Not yet. Do tell.

That was a sailboat I was on, sponsored by the same Committee for Non-Violent Action that sailed from Sausalito in 1962. We were trying to stop hydrogen bomb testing around the Marshall Islands and thought they would hold off as long as we were out there on the water. At the very least, we thought we would mobilize public opinion by our presence.

So did it work?

(Barton laughs.) It was the last of the atmospheric tests that the US did, so maybe we helped with that. They did underground testing from then on. We obviously didn’t stop the arms race.

No, but nice try.

And we got nowhere near the Marshall Islands! We got arrested and towed back to San Francisco by the Coast Guard about a hundred miles past the Golden Gate. They probably saved our lives. (Barton is really laughing now.)

We were sent to the Santa Rita jail/farm for eight months. It’s an Alameda County facility where many protesters were taken.

Probably lots of time to meditate there.

Oh yeah.

Okay, just two more questions. As an old, long-distance walker, what’s your favorite walk around here?

Right outside my door. Just down Morelli Lane. That’s all it takes.

Of course. And finally, Barton, what gives you hope?

(He takes a long time to consider this one. He sits there quietly for a while pondering.)

That stumps me. I would say that I’m not moved by hope. Hope implies an expectation of the future. Our future is probably fucked for all sorts of poly-crisis reasons. I go from inspiration and not hope. An inspiration is about right now, and right now is filled with the beauty and kindness of West Sonoma County. That’s my inspiration.

Amen. What a perfectly Zen response. Well, thank you, Barton, for the inspiration that you have been to me and everyone else who gets to experience the peace and kindness that emanates from you. It’s a gift. Much gratitude to you.

I nominate Barton Stone, or Myozen as we know him at Stone Creek, to be Sebastopol's first Community Cultural Treasure. He is simply a gift.

Pro active inspiration is an appropriate replacement of passive hope. Passivity will not get us beyond our current fog of chaos and fear. Thank you for this illuminating profile.