Sonoma County's mountain lion expert has a message for west county

Mountain lions are few and far between, but unprotected livestock pose an irresistible temptation

Sonoma County mountain lion expert Dr. Quinton Martins estimates that there are about 75 mountain lions in Sonoma County. That doesn’t sound like very many, but when you combine them with a large number of small farms with unprotected farm animals, a handful of big cats can cut quite a swath.

In August, the Press Democrat reported on a farm in Lake County that lost 11 alpacas to mountain lions—half died immediately in the attack, and the remainder had to be euthanized due to their wounds.

Sonoma County isn’t immune. This summer, a frustrated West County farmer posted on Nextdoor that she had lost more than half of her sheep to mountain lion attacks this year.

“We used to have like 30 to 35 sheep. We now have 11 sheep,” the farmer told the Sebastopol Times in August.

The farmer, whom I am going to refer to as Anika, said she and her family had been working their farm for 15 years. They hadn’t had trouble with mountain lions in the past, though they’d had bobcat issues. The trouble started, she said, when first their llamas and then their labrador, Sierra, died.

“We had no idea we had all these predators until Sierra died of cancer at nine years old. Between her and our two llamas, we were covered. Nothing ever happened here. Once she died, everything started coming in,” Anika said.

The mountain lion attacks on their sheep happened in January of 2025 and continued through summer. She posted on Nextdoor last month, December 2025, that the mountain lion had struck again, taking down another one of their sheep.

Martins worked with Anika and her family earlier in the year. “They did suffer a number of losses and one of the key reasons being is that the animals were unprotected … They live in a really good mountain lion area—it’s like an intersection between different individuals’ territories so it’s a really good spot to have more than the usual activity,” Martins said.

Livestock are not mountain lions’ primary prey. “They much prefer to eat deer,” he said. “Our diet study has shown that at least 75% of mountain lions’ diets are deer.”

According to this same study, only about 10% of a mountain lion’s diet in the North Bay consists of small livestock.

Livestock may not be mountain lions’ first choice, but Martins said, “Essentially any mountain lion will kill unprotected livestock at some point in its life given the chance. Goats and sheep are most susceptible to mountain lion predation, followed by domestic and feral cats being targeted quite a bit.”

Anika said that her family has been trying to deal with the predation by fencing, but it just hasn’t been enough. Martins suggested that if building a fully protected enclosure wasn’t possible, adding shade cloth to the fencing could help since mountain lions are primarily visual hunters. They added shade cloth, and for a while that seemed to work. Until it didn’t.

As she wrote on Nextdoor in December, “We’ve spent $40,000 on fencing! Mountain lions jump 15 feet!!! Who has 16-foot fencing? No fencing will keep them out!”

They also purchased a Great Pyrenees, a kind of livestock guard dog, but it’s still a puppy and too young to guard their livestock.

Anika said her family is trying to create full enclosures from their three three-sided horse paddocks by fencing off the fourth side and covering it with shade cloth. They moved the animals out of the large three-acre pasture next to the forest (where the previous attacks had happened) and put them in pens close to their house. (She said you can’t pen all your animals into a single enclosure—for example, you can’t put a ram in the same pen with its female offspring for obvious reasons.) Although the goats are amendable to spending the night in an enclosed shelter, the sheep are not and she has to lure them in there by putting their food inside the shelter. Her husband put up expensive cameras to alert them by phone to the presence of large animals in the vicinity of the pens.

All this wasn’t enough to save their pregnant sheep, Lizzie, however, who was killed in December.

In the meantime, they are working to create full enclosures in all of their pastures, which is an expensive undertaking.

Although she agrees with Martins that a fully enclosed structure is necessary to keep animals safe from mountain lions, Anika said that she feels Martins has unrealistic expectations of small farmers.

Several years ago, Anika watched a webinar with Martins and Sarah Kaiser of Wild Oat Hollow in Penngrove.

“The way he was talking to farmers was like, basically, if you want animals, you have to pretty much have a lot of money: you have to have a barn. You have to have this, you have to have that. And the farmers were like, ‘Farmers don’t have a lot of money.’”

Martins said predation on small farms with unprotected livestock make up many of the calls he gets at his nonprofit, True Wild Conservation. A lot of his work centers around trying to get people to keep their animals safe.

“It really is the responsibility of the owner to protect their animals where there are risks,” he said. “Throughout our study area, we have seen that many people are not protecting their animals sufficiently to keep them safe from mountain lion predation. Living in mountain lion habitat and not protecting your animals is an animal welfare issue. The stress and trauma on livestock in a depredation event must be incredible.”

“If you know that mountain lions live in your area, you can also know there is a high likelihood that at some point you’re going to have an attack, and if you’re not protecting your animals, you could lose all of those animals in one night,” Martins said. “These mass depredation events are not abnormal behavior by the mountain lions. Rather it is more a response by the mountain lion when presented with an unnatural opportunity.”

“Many people who call me say, ‘This never happened before!’ when they have had a loss,” Martins said. “But the thing is that, statistically, it makes sense that it doesn’t happen very often to an individual, because one mountain lion can easily have 5,000 to 10,000 private properties in its territory—and you end up being just one of many people. The problem is that you never know when it’s going to happen, but it is very likely to happen at some point in time, especially if you are living in a high-use lion area. Essentially, you are creating a situation which just shouldn’t happen in the first place.”

Martins would like to get the word out about how homeowners and small hobby farm owners can protect their animals from predation by mountain lions. There’s a useful guide, Coexisting with mountain lions: A guide for pet and livestock owners of the North Bay, on his website.

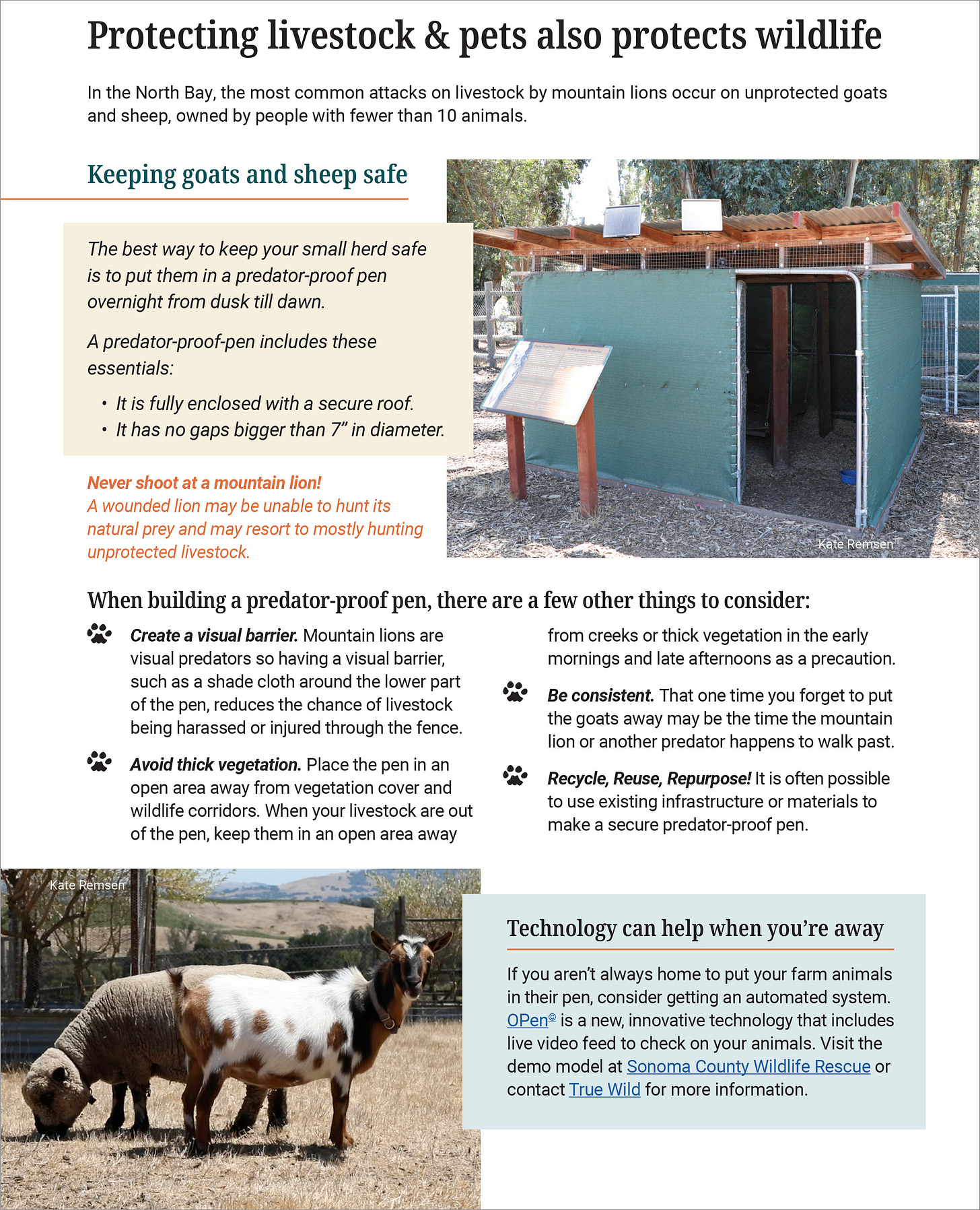

For sheep and goats, the guide suggests, “The best way to keep your small herd safe is to put them in a predator-proof pen overnight from dusk till dawn. A predator-proof-pen includes these essentials: It is fully enclosed with a secure roof, and it has no gaps bigger than 7” in diameter.” There are instructions on this page about how to do this.

For dogs and cats, he suggests people keep their pets inside the house at night or build a roomy cat cage (or “catio”) or fully enclosed dog run.

For more information, see Martins’ website Truewild.org or the Living with Lions webpage.

Your headline commands that lions are few and far between. How rigorous is this? As a west county resident with several game cameras, I suspect this couldn't be further from the truth. We have mountain lions on our property *weekly*. This shouldn't diminish the very important need to protect and defend mountain lions and their habitat. But the suggestion that they are in grave danger of population losses and diminishment doesn't seem be close to the truth from my rural corner.

As a LGD (Livestock Guardian Dog), Great Pyrenees owner, I have no doubts about their ability to guard and protect their charges. However, if predators, e.g. mountain lions, which often travel in groups, are known to be in the area, it is unfair to expect a single dog to stave off an attack without grievously getting hurt itself. Many LGD are used to guarding as teams with their pack. Therefore it is a good idea to have at least two, if not more LGD. (Be aware Great Pyrenees are nocturnal and their first line of defense is barking--loud barking, often at falling leaves a pasture away, off and on all night.)