History Matters: A Pleasant Surprise from the Supreme Court

A local history teacher muses on a class trip to a iconic civil rights site, giving context to a recent Supreme Court decision

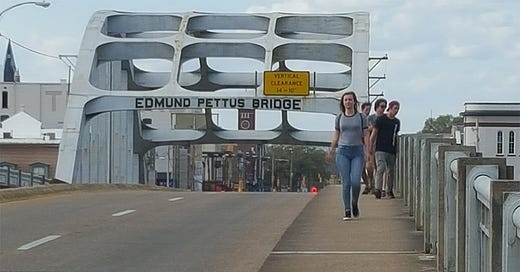

Even here in distant California, most of us have heard of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where about 600 civil rights marchers were attacked by local law enforcement with billy clubs, tear gas, and horses in 1965.

With the Supreme Court last week striking down Alabama’s districting map (in Allen v. Milligan), I am reflecting on my walk across that bridge with 15 El Molino students a few years ago.

At the foot of the bridge is the powerful Museum of Slavery and Civil Rights where we were immersed in the interactive experience of life in west Africa, kidnapping, middle passage, auction, and life of the enslaved. There, original marcher and long-time member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Annie Pearl Avery welcomed us and shared her memories in vibrant, terrifying detail before we started our ascent over the Alabama River. Like the marchers of 1965, we couldn’t see what awaited us at the east end of the bridge until we got to the summit midriver. Unlike those marchers who experienced beatings, we were greeted by silence, interrupted only by the passing of a few cars.

“It was powerful and eerie to be in that place and know that the fight for voting rights wages on, in all kinds of forms,” traveler and former El Molino student Ella Griffith recently said. She now trains to fight fires of a different sort in the Trinity Alps.

This week’s surprising Supreme Court case used the 1965 Voting Rights Act to strike down today’s Republican-drawn map that confined a Black majority to only one of seven districts despite Black citizens composing 27% of Alabama’s population. (Predictably, the state is represented in the House by one Democrat and six Republicans.) The 5-4 decision is interesting because the Court in 2013 gutted the part of that same Act that tasked the federal government with approving all districting maps in states with a history of discrimination. (See Shelby County v. Holder.)

That very discrimination begs a look into the man after whom the Edmund Pettus Bridge is named, a U.S. Senator from 1897 to 1907, years of particularly intense racial hatred. Pettus’ winning senatorial campaign highlighted his role in organizing Ku Klux Klan activities and all he did to restore white power to the post-Confederate south. Not only did he hail from an elite slave-owning family, he was a committed white supremacist who exalted his role as state leader or “Grand Dragon” of the Alabama KKK.

For context, Alabama led the nation in lynchings with Pettus’ Dallas County among the worst counties. Of the 350 lynchings documented in Alabama from 1877 to 1950, 19 were in Pettus’ Dallas County, the second highest in the state. No one was ever prosecuted, surely in part thanks to Pettus, a high-powered lawyer and then U.S. Senator during the period. Pettus surely organized many of those 19 lynchings although a man of his standing probably wasn’t actually among the mob with the masks, machetes, ropes, and guns. He certainly supported and protected the still-faceless killers.

The bridge was named in 1940, a time of keeping Blacks down and terrorized, far from the voting booth.

No wonder Martin Luther King Jr. chose the Pettus Bridge to bait Sheriff Jim Clark into a violent showdown with the march to Montgomery on March 7, 1965. King and his supporters were drawing attention to the fact that despite Black citizens accounting for 30% of Alabama’s general population, the state’s voting rolls were 99% white, according to the 1960 census.

A petition circulating today to rename the iconic, and now-ironic, symbol of civil rights has over 160,000 signatures. But late Congressman John Lewis, who marched that bloody day in 1965, opposed renaming the bridge. If Pettus the man personified vicious racism, perhaps the crossing of the bridge with his name, located on a vital state highway, symbolizes crossing into a new age in which Lewis’ coffin was honored on its way to lie in state at the capitol 55 years later.

Thanks to this week’s Court decision, maybe the Voting Rights Act that Lewis and King inspired still assures Alabama’s 1.3 million Black citizens of fair, if not easy, representation in the voting booth.

John Grech has been a West County high school history teacher for 25 years and is working on a book about adventures abroad with students.