History Matters: The Demise of the Whig Party

The fight over Kevin McCarthy's speakership made our history columnist wonder, 'What does a party’s disintegration look like?'

We are thrilled to welcome back John Grech, a history teacher at El Molino and then Analy High School, and the author of the history column, “History Matters,” which originally ran in Sonoma West Times & News.

After watching the Republicans take 15 ballots to agree on a House Speaker, the most since the Civil War era, I wonder if we are watching the demise of the Republican party before our very eyes?

What does a party’s disintegration look like? John Adams’ and Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists were more of a faction than an organized political party, and their demise wasn’t terribly traumatic to most Americans. After all, the Alien and Sedition Acts, which they created, seemed an obvious violation of the First Amendment, and refusing to support Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, doubling the nation’s size was, although principled, downright unpopular.

Perhaps the end of the Whig Party in the 1850s is a more prescient study. The Whigs stood for infrastructure improvements from a robust central government (by 19th Century standards), a tariff to raise revenue in the absence of income tax, and the preservation of slavery which they called “domestic labor.”

The year Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin took the country by storm about a kind-hearted enslaved man sold from one cruel owner to another, the Whig Party removed the issue of slavery from its platform altogether. That was because its northerners and southerners could not agree on what to say about the most massive, emotional issue of the day. Whether slavery would expand westward could not be postponed any longer.

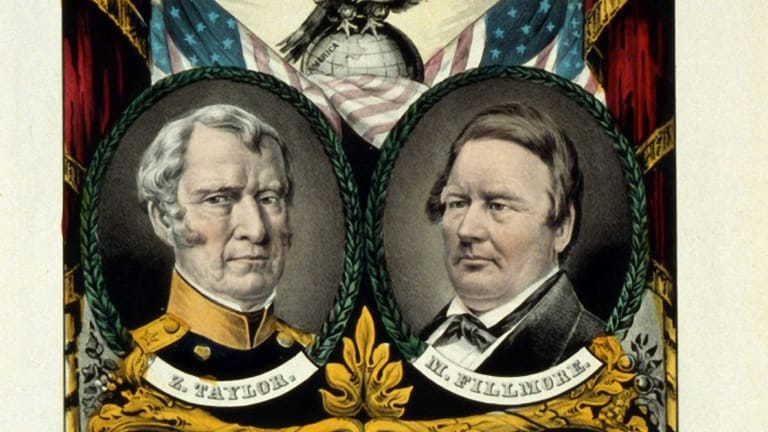

Even the Whig presidents of the era were contradictory on the subject. Zachary Taylor, owner of a thousand enslaved people on his Louisiana plantation, railed against other slave owners who spoke of seceding from the United States, saying he would personally lead an army against traitors as generals are wont to do. It didn’t come to that because Taylor suddenly died of stomach cramps after he apparently drank too much cherry juice on a hot day. and was replaced by his vice-president, the pro-slavery northerner Millard Fillmore, who didn’t have much to say.

Congress’ passage of the ill-advised Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing new states to decide the slavery issue for themselves north of 36˙30’ latitude (scrapping the Missouri Compromise line) proved too much for the party to even exist. In the next presidential election Whig Fillmore lost every state but one, Maryland, with its own mixed feelings on slavery. It was a fitting end to a party that had lost touch with the nation as a whole.

Its northerners started the Republican Party, soon to nominate Abraham Lincoln, and its southerners disappeared into a Constitutional Union party in a region moving away from union.

If today’s bickering Republicans disappear as we know them, what would be considered the beginning of their end? One possibility might be Donald Trump’s advocating an assault on the Capitol and dozens of Republican lawmakers continuing to dispute the 2020 election, which was not very different from southerners’ reaction to Lincoln’s election. It’s touching that in his acceptance speech, new Speaker Kevin McCarthy focused on the spot where Lincoln sat in the old House when he was a young Congressman.

I wonder if Federalist President John Adams’ words about his party would ring true of today’s Republicans: “No party… knew itself so little or so vainly overrated its own influence and popularity as ours. None ever understood so ill the causes of its own power, or so wantonly destroyed them." What he feared about the House in particular was that it would be “run by meanness, not greatness…noise, not sense”.