Peter Oliver's Electric Car Kit For Schools

Students and teachers learn to build an electric car together

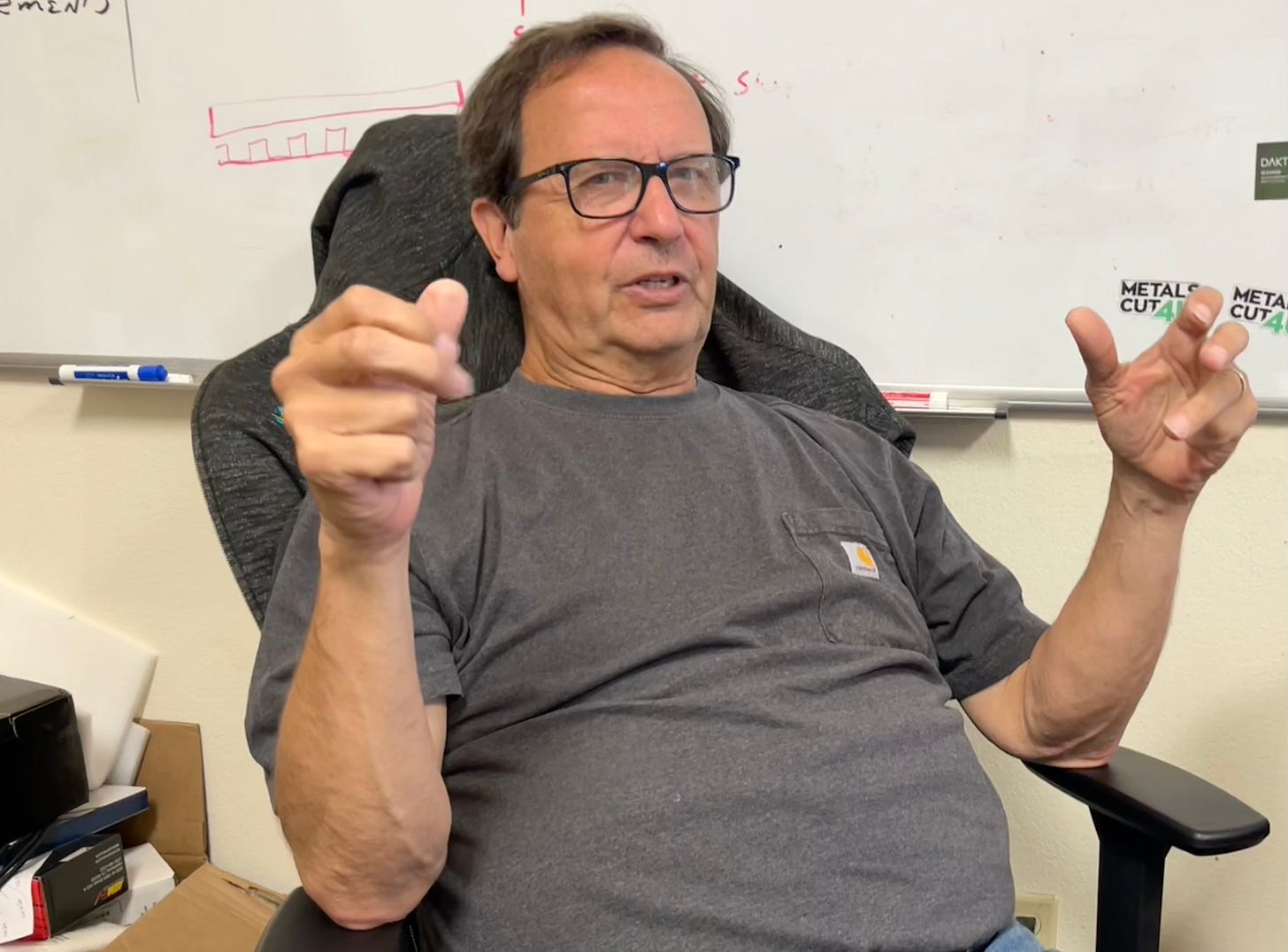

In 2006, Peter Oliver retired early at 55 from a computer networking company that he started 25 years ago. Work had become a grind. “I wanted to do something fun,” said Peter. “The last thing I did that was fun was racing cars in high school.” He knew that he wanted to get back into cars. “I didn’t want to get dirty,” he explained. “So I decided to work on electric cars.” That’s how The Switch Lab got started in Sebastopol.

In his office on Morris Street, The Switch Lab employs 13 people who build electric car kits that are shipped to high schools and colleges around the country. On my June visit, it was the last day of a week-long workshop that prepared teachers to work with students to build the electric car from the kit.

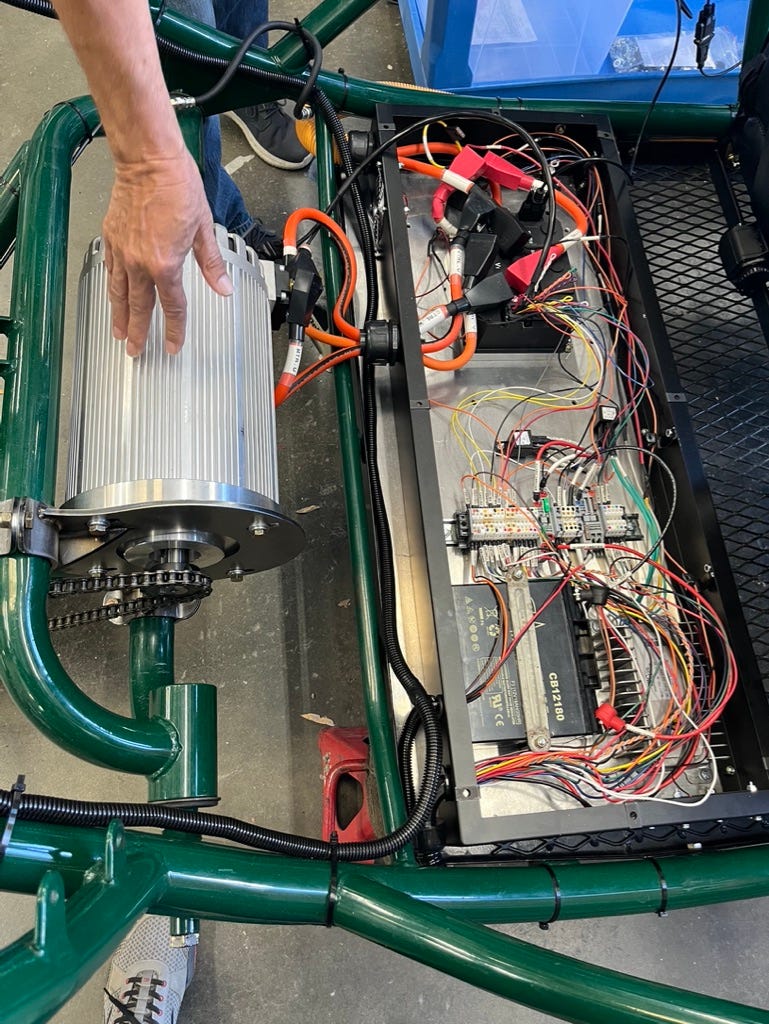

Each kit comes with a welded chassis that I thought looked like the frame of a boat. Peter confirmed that its shape was influenced by a Chris Craft boat but front and back are reversed. Inside the chassis are boxes filled with all the components including wiring, batteries, motor and steering wheel.

By building an electric car, students gain hands-on experience working on electric cars. “They develop the ability to work as a team in a work-like environment,” said Peter. “They learn to communicate with each other.”

A Rocky Start

His entry into electric cars was teaching a class at the SRJC in electric car conversion. He had students remove the combustion engine from a car or truck and then replace it with an electric motor. He developed the curriculum so that students understood how an electric car works. “Students were really excited by it,” said Peter.

Soon after, he started a company building electric cars that ordinary people might drive around town. His prototype vehicle was fast, economical and street-legal but it wasn’t affordable. He changed course and designed a kit car that could be used to teach a class on electric cars and offer students a challenging hands-on experience.

He began teaching teachers how to build the kit car. “It was rocky at first,” he admitted. “I'd have all of the teachers stand up and introduce themselves. The first guy stood up and said, ‘Hi, my name is Mike. I HATE electric cars. My boss told me if I didn't take this class, he'd fire me. And now I can't do my race cars anymore. I have to do these electric cars.’”

Peter wondered that “maybe I hadn't quite picked the winner I was hoping for,” but he didn’t give up on the electric car class or Mike. “By the end of the class, Mike was the most engaged student. He was helping all the other students.” Peter remembers Mike as the first one to complete building the car. “He was adamantly against electric cars,” Peter said, “but then he realized that it was a lot of fun and it was really something that would be good for the students.”

The first year Peter sold three kit cars, and the next year he sold three more to schools. “Then we went up to five and it's been growing every year since then.” Most of the sales were to schools in southern California. “We didn't have anything local in Sonoma County until Sonoma Clean Power sponsored five vehicles, four or five years ago.” (West County High School doesn’t offer a class based on The Switch Lab kit.) “Since then, Sonoma Clean Power has been sponsoring two or three a year locally. I think we have 10 or 11 schools locally,” Peter said.

The Switch Lab Kit

This year, Peter expects to sell about 80 kits. At a price from about $40-55K, depending on different options, the kits are expensive. “The good news is that we have schools that have used the kit over and over again for five or six years at this point,” he said.

The heart of the electric car is the electric motor and the battery that powers it. The specs for the kits can be found here. There are thousands of parts that need to be assembled to have a working car.

The kit ships with a manual that provides step-by-step instructions and describes what tools are needed. “If you're gonna install the floor,” said Peter, “there are instructions for the student to go get the box with the floor mounting hardware.”

I asked what typically happens to the finished vehicle. “Some schools drive it around or they'll show it at a parade,” he said. In Hillsborough, the middle school and high schools time the build to participate in the Hillsborough parade and the students walk alongside the vehicle.

Some schools perform tests to see how much energy the electric car uses going up and down the street. Others have wrapped a skin around the vehicle to make it more aerodynamic. “They tested it before and after to see how much of a difference it made,” said Peter. Most classes will take the finished car apart at the end of the semester so the next semester’s class can reuse the kit.

Teaching Teachers

I asked Peter what types of teachers attend his workshops. “The vast majority are auto shop teachers, probably 60%, but we have engineering teachers, science teachers, teachers of physics classes,” Peter said. “I had one computer programmer and a wood shop teacher.” He doesn’t care much about their background as long as they are motivated to learn. “The auto shop teachers might have trouble with electricity where the engineers might not, but the engineers would have a little more difficulty aligning the front end or installing the brakes,” he added.

The teachers learn about all the component parts of the electric car. “They learn about safety, how to manage the class, what to expect, and then how to put the vehicle together,” said Peter. The morning session is a lecture and in the afternoon, the teachers assemble a car together.

There are now Certified Switch Instructors who teach the teachers. One of them was leading this workshop (above) and he was headed to Portland the following week to hold a training class for another 12 or so teachers.

“I remember I used to teach students and then I taught teachers and now we teach the teachers who teach the teachers,” said Peter.

Real-life Work for Students

“What we're learning is that those teachers are inspiring kids,“ said Peter. “The process is what I'm after,” he explained. Building a kit car is multi-disciplinary, hands-on learning that can fit into a STEM curriculum or Career and Technical Education (CTE).

“When I went to college and started with computers, I started being a lab assistant,” he said. “For a couple years, I helped students with computers. And that was a big differentiator when I was looking for my first job. After I got that job, I asked the guy later why he hired me and he said, ‘because you had that initiative and that experience.’” He wants students to gain that kind of experience with electric cars today.

“A University of Michigan did a big study with manufacturers and parts manufacturers and anybody related to transportation and they found out what they're looking for in employees,” said Peter. “What they're really looking for beyond anything else is the ability to work as part of a team.” They also emphasized the ability to communicate both in writing and verbally. With those basic skills, employers are willing to provide more specific training themselves.

“We're showing students what it takes to be successful,” said Peter, adding that he sees students gaining confidence in what they can do. “With kits, you can learn so much,” said Peter. “Now that more and more people are working on electric cars, working on batteries, working on motors, we are starting to see the evolutionary byproduct of all that brain power coming together.”

Good Fun

“I started this as a give-back hobby that was fun,” Peter reflected. “Now it's grown a little bit.” When he was working for a living, he played golf three days a week and never on the weekends. Over the last year, he’s only played golf three or four times. “This is what I do now for fun. It's a different perspective.”