Remembering the fight to make Sebastopol a “nuclear-free zone”

Forty years ago, local activists kicked off a campaign to declare Sebastopol "nuclear free"

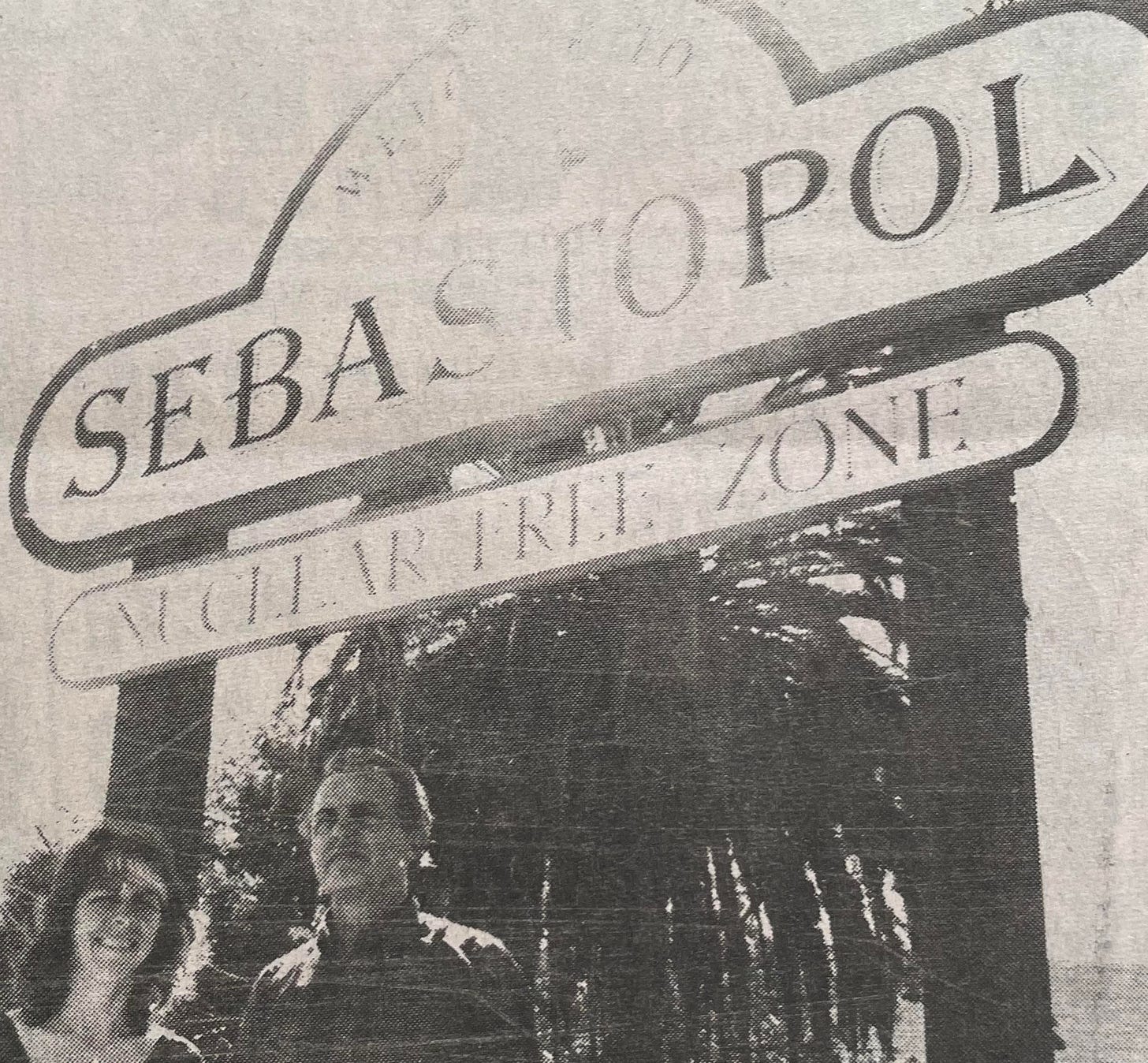

When you drive into Sebastopol, an official city sign welcomes you to town and informs you that you have entered a Nuclear Free Zone.

Those too young to remember the anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s and 80s can be excused for thinking, “Wha…?”

This is the story of that sign and the movement behind it.

The long march of the anti-nuclear movement

The anti-nuclear movement in the United States began almost as soon as the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in August of 1945. J. Robert Oppenheimer, often called “the father of the atomic bomb,” became part of a growing movement opposed to the development of nuclear weapons in the 1950s. He paid for his opposition with the loss of his U.S. security clearance and the loss of his job at the Atomic Energy Commission.

But the movement continued apace, growing over the years on college campuses, eventually blending with the anti-war movement of the sixties and the burgeoning environmental movement of the 1970s.

To be clear, nuclear energy and nuclear weapons are separate things. One heats your home, the other blows it up. But they’re entwined because the process of producing nuclear energy also produces material that can be used in nuclear weapons. Nuclear energy production also produces radioactive waste, which is difficult (some say impossible) to store safely.

But it wasn’t until the nuclear accident at Three-Mile Island in 1979 and the 1983 hit movie, “Silkwood,” starring Meryl Streep and Cher—about an accident at a plutonium processing plant—that opposition to nuclear energy went mainstream.

Matthew James, a retired professor of geology, who taught at Sonoma State for over 30 years, said there were also local reasons behind Sebastopol’s decision to go “nuclear free”—reasons connected to PG&E’s failed attempt to build a nuclear power plant in Bodega 20 years earlier.

James noted that the Bodega Head nuclear power plant was the only power plant in California that was ever stopped by citizen protest.

“They protested all the other ones, but they were built anyway,” he said.

From the sixties onward, there was also a sea change in people’s attitude toward authority.

“People tended to believe that the government was looking out for their best interests and slowly, people came to realize that the government doesn't always look out for your best interest,” said James. “Therefore, you have to question what they’re doing.”

Sebastopol picks up the gauntlet

It was in this environment that, in 1984, Sebastopol architect John Hughes formed a group called Nuclear Free Sebastopol, which worked to get the Nuclear Free Zone initiative on the Sebastopol ballot. (Interestingly, Hughes was also known for appearing at the Apple Blossom Parade every year wearing a gorilla suit.)

According to Sebastopol Times articles from this period, the group began gathering signatures in January of 1985 and by June had enough signatures to put the four-paragraph initiative on the ballot.

According to an article in the Sebastopol Times from May 1985, “Sebastopol appears destined to become an official ‘nuclear-free zone’ as the result of a petition signed by 25 percent of the city's voters. Sebastopol architect John Hughes, who began the petition drive, needed only 15 percent of the city's registered voters to force a special election on the petition that forbids transportation, storage or processing of nuclear weapons within city limits.”

Clare Najarian, a founding member of Nuclear Free Sebastopol, was instrumental in the signature-gathering effort.

Najarian was quoted in a Sebastopol Times article, dated June 12-18, 1985: “We all worked together to do what needed to be done: phone calls, letters. We did a lot of door-to-door and kept it an educational thing, not an argumentative thing.”

The issue came before the Sebastopol City Council on June 3, 1985.

Richard Johnson, who was on the city council at the time, remembers that everyone was pretty much in favor of putting the initiative on the ballot. In fact, they were required to do so by law because of the signature-gathering campaign.

Not everyone on the council was happy about this, however.

In a Sebastopol Times article, dated May 30 to June 6, 1985, reporter Bruce Robinson (who went on to become news director at KRCB for many years) wrote: “Sentiments on the council were sharply divided on the merits of the measure. Councilman Bill Rovetini complained that the language contains ‘no exemptions for national defense,’ but said he was in general support of the rest of the petition, other than that ‘short-sighted’ omission.”

Robinson also wrote that Councilmember Howard Reesser was “resolutely opposed” to the measure. In the end, the council voted 3 to 2 to place the measure on the ballot.

The measure was initially scheduled to go on the November 1986 ballot, but after pressure from activists, that was moved up to the June 1986 ballot. It was named Measure A, and it passed with 73% of the vote.

According to a Sebastopol Times article, dated June 12-June 18, 1986, activists made sure the city posted the new “Nuclear Free Zone” sign the day after the vote was made official.

Sebastopol’s Nuclear Free Zone ordinance reads as follows:

8.20.010 Declarations.

The people of Sebastopol hereby declare it to be a nuclear-free zone. No nuclear weapon shall be produced, transported, stored, processed, disposed of, nor used, within Sebastopol. No facility, equipment, supply or substance for the production, storage, processing, disposal or use of nuclear weapons, except radioactive materials for medical purposes, shall be allowed in Sebastopol.

8.20.020 Signs.

The City Council shall place and maintain a sign reading “Nuclear-Free Zone” at all City limit signpost locations. The sign shall be clearly visible and its letters at least equal in size to those on the nearest City limit sign.

8.20.030 Violation and penalties.

Violation of the nuclear-free zone provisions is a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail or a $500.00 fine or both.

8.20.040 Appeal.

Conscious of the magnitude of destructive capacity of modern nuclear weapons, we recognize that our proposal would have little meaning on its own. We, therefore, appeal to our neighboring communities to make similar statements on behalf of the citizens they represent.

“The passage of it resulted in us putting a new banner on the ‘Welcome to Sebastopol’ sign, and that was about it,” former councilmember Richard Johnson said. “But I think the activists’ intentions were well-intentioned, and frankly, I subscribe to those intentions. I think we kind of looked at each other on the council and said, ‘Well, we don’t think we’re going to be involved in deciding the fate of World War III. We don’t think there’s any nuclear arsenals that are going to be established in Sebastopol or weapons built in Sebastopol. But what the hell, it’s a no-brainer. It’s a no-harm, no-foul.’ And so that’s the kind of attitude it was. And it got passed, God bless it. God bless us for passing it.”

Johnson said they took a bit of ribbing from other cities.

“When we put it on the sign, we took a little bit of shit from Santa Rosa and some other communities about it, because, you know, they rolled their eyes, like, ‘Oh, there goes Sebastopol again.” But, you know, it's an okay thing. I mean, it was an expression of community sentiment and that, for me anyway, is an okay thing.”

Other nuclear-free zone efforts in Sonoma County

There were two other attempts in Sonoma County to declare other nuclear-free zones: one in Camp Meeker, which took place before the Sebastopol campaign, and a county-wide measure, Measure B. Both went down to defeat.

Longtime local activist Mary Moore, 90, best known for her protests at the Bohemian Grove, was involved in both the Camp Meeker and Sebastopol campaigns.

Though she cut her teeth as a civil rights activist, Moore had previously fought as a part of the Abalone Alliance against the building of a nuclear power plant at Diablo Canyon on California’s Central Coast.

“The Abalone Alliance believed in direct action and getting arrested and civil disobedience, that kind of thing. So it was always seen as more radical by some people in that movement,” she said. “I got arrested at Diablo Canyon many times, along with a lot of other people. Eventually, we moved up here.”

Once she did, she formed a subgroup of the Abalone Alliance called SoNoMore Atomics.

While the effort to declare Camp Meeker a nuclear-free zone failed—the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors voted it down 3 to 2—that didn’t stop some community members from simply declaring it “Nuclear Free.” When activists nailed a “No Nukes” sign to a tree in Camp Meeker, the sign was taken down.

A 1985 article in the Press Democrat described it this way: “Mary Moore, one of the organizers, said that without an official sanction from the county, residents would enforce the law themselves. ‘If they decide to take nuclear weapons down Bohemian Highway, we’ll go down and sit on the road.’”

“The difference in class viewpoints was very prevalent in the anti-nuke movement, and I was a big part of that movement,”Moore said. “But we took a lot of shit, to be perfectly honest, from people who thought we were too radical. And that's not a new concept at all,” said Moore.

“There's a lot of good middle-class people, but they're well-protected because they have the money to do that and live where they are safer,” said Moore. “If people want to focus on one issue that’s fine, but in the analysis, they need to understand how connected all of these issues are by who’s profiting from them.”

Speaking of profiting…

There was also an attempt to make all of Sonoma County a nuclear-free zone. Anti-nuke groups placed Measure B, a county-wide measure, on the November 1986 ballot. It was voted down 60% to 40%.

In the run-up to the county-wide election, editorials emphasized the potential economic impact of the measure on several large, local manufacturers.

According to an editorial in the Sebastopol Times & News, dated Sept. 25-Oct. 1. 1986, “Careful examination of the language in Measure B reveals one deadly phrase, ‘or any component of a nuclear weapon,’ which would effectively outlaw the manufacture of any product which could later be used in a nuclear weapon. Because the same micro-processing components produced at companies such as Hewlett Packard and used in consumer products and jet airplanes could also be used in weapons technology, their manufacture could be banned under the broad scope of the ordinance.”

Another editorial from the Sebastopol Times’ Open Forum section, from Nov. 1986 said, “Another poor decision was to have the prohibitions apply to component parts that have many uses aside from nuclear weapons, or at least not be clear on this issue. These two items, more than anything else, woke the sleeping giants of Hewlett-Packard and Optical Coating and led them to mount a major campaign against the measure.”

Ernie Carpenter, who lives in West County, was on the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors at the time.

“The issue of war comes and goes, but it never really goes. And the issue of nuclear weapons never really goes.” said Carpenter.

“There were a couple of businesses that kind of led the charge against [Measure B], because it hurt them. I think the populists mainly turned it down because they didn't see it as the business of local government,” he said.

“[But] it must have worked, because we haven't had any nuclear weapons or applications to build bombs in Sonoma County. It's really an expression of the people, and the people need to keep making these expressions and keep pushing on the gates. It does have an impact, but it's not always clear-cut. Ask the suffragettes—it takes a long time.”

Looking forward

When asked if he saw a future where the production of any bombs or weapons would be prohibited from being manufactured or transported through Sonoma County, Carpenter said, “Never say never.”

Some local activists, for example, have protested against General Dynamics, the world’s fifth-largest weapons manufacturer, which operates a facility in Healdsburg, which has a role in producing weapons to be used in Gaza.

Though Carpenter has been a staunch supporter of Israel, he said you can never tell how the political winds of history will shift. “I never thought that the Soviet Union would fall, right? I never thought Trump would be elected. So what this has proven to me is that anything is possible in politics. We should take nothing for granted. So as it turns out, these days and times, there’ve been quite a few reversals in government, right? I would never say never to anything or that nothing couldn’t happen.”

Thanks to the West County Museum

This story was made possible by the wonderful Sebastopol Times archives at the West County Museum. Thanks to Museum Director Donna Pittman for hauling these giant volumes out of the archive and loaning them to us during the writing of this article.

Wow! That is a real hike down memory lane. Good job, Albert and Laura! And thanks to Donna P for tending the historical files!

How interesting how this article ties together those activists that accomplished making Sebastopol a Nuclear Free Zone with activism across the spectrum of different issues starting in the 60’s.