Roundup: Blackberry Mania

The Barlows, Burbank and Birds Explain Everything

Out in the back of Ragle Park, along the entire Rodota Trail, down by the Laguna, on roadsides throughout Sonoma County, you can find blackberries this time of year as well as people filling pints and buckets with them. On Saturday, I came across Jenny and Matt Parks picking blackberries in the back of Ragle Park. A young, excited voice cried out behind a bramble: “Mom, it’s blackberry mania.” Jack emerged, smiling, with a handful of blackberries and he added them to a container held by his mom.

How did blackberries get here in the first place and why are they everywhere?

The Other Barlow Legacy

I asked Donna Pittman of West County Museum that question. “Blackberries were once the major crop of the Barlow family,” she told me. “I think their primary acres were in Green Valley, maybe Occidental Rd/Barlow lane area. That was early in century for them, but berries remained important for a long time.” She told me that the Barlow family’s large blackberry farm for many years was run by Laura Barlow after the death of her husband, Thomas.

Inheriting the family farm, Thomas Edgar Barlow had accumulated one-hundred and sixty-four acres of land around the end of 19th century. Its location was north of Sebastopol, off Occidental Road at Barlow Lane. In a biographical sketch of Thomas Edgar Barlow, Tom Gregory in 1911 wrote: “He was one of the pioneer fruit raisers of this locality, and at one time produced more blackberries than any individual on the coast, having ninety acres of the fruit.”

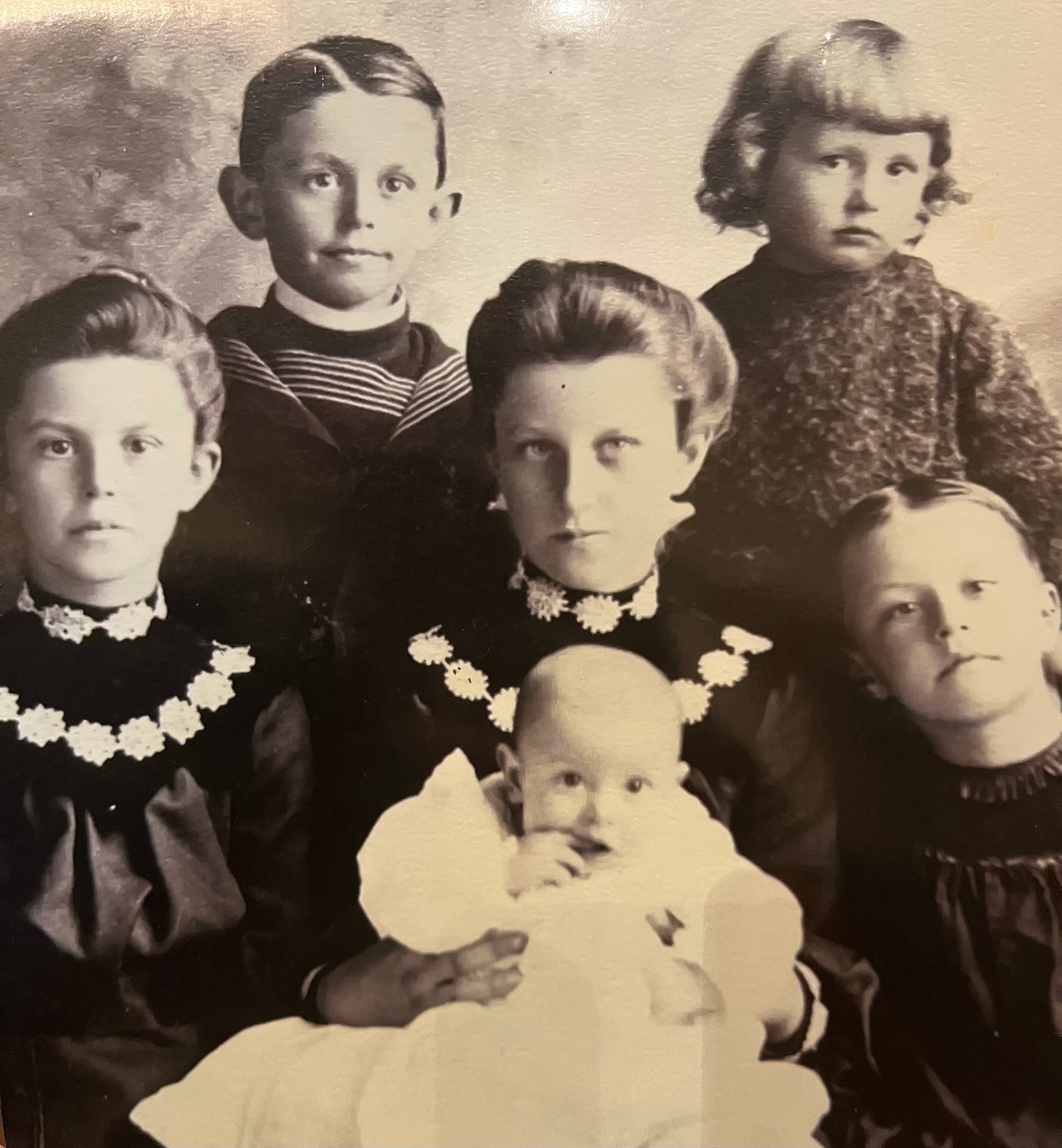

In 1904, Thomas E. Barlow died at age 37 and his wife, Laura, at age 35, took on the management of the farm in addition to raising six children. “She is no less enterprising than her worthy husband,” wrote Gregory.

A 2021 Facebook post from Sonoma County Farm Bureau quoted Sunset Magazine: “The Sebastopol region alone produced 80% of California's berry crop, and in 1910 a total of 1,825 tons of berries were shipped from here. Berries from Laura E. Barlow's 100-acre property, considered to be the largest berry ranch in the world at the time, likely made up the bulk of this shipment.”

The Sebastopol Times of July 14, 1915 quoted a story published in the Country Gentleman magazine, out of Philadelphia, saying it gave a “splendid compliment” to Laura Barlow.

“Seven years ago the berry growers of Sonoma county, California were in a desperate plight. The canners would pay thirty dollars a ton for loganberries, and no more. For blackberries they would pay twenty-five dollars a ton and when crops were heavy, they’d beat down the price to twenty dollars a ton. Discouraged growers began to pull out their berry bushes and plant apples, for it had been demonstrated that the Gravenstein would pay good interest on a thousand dollars or more an acre…

One of the wisest of the berry growers, Laura E. Barlow, instead of taking twenty dollars for her blackberries, began to dry them, dipping them first into syrup and spreading them on trays in the sun. She produced something so fine that it brought her two and half cents a pound, which meant fifty dollars a ton… A few other growers tried the same thing the next season, and the canners for a moment loosened their grip and raised their bid.”

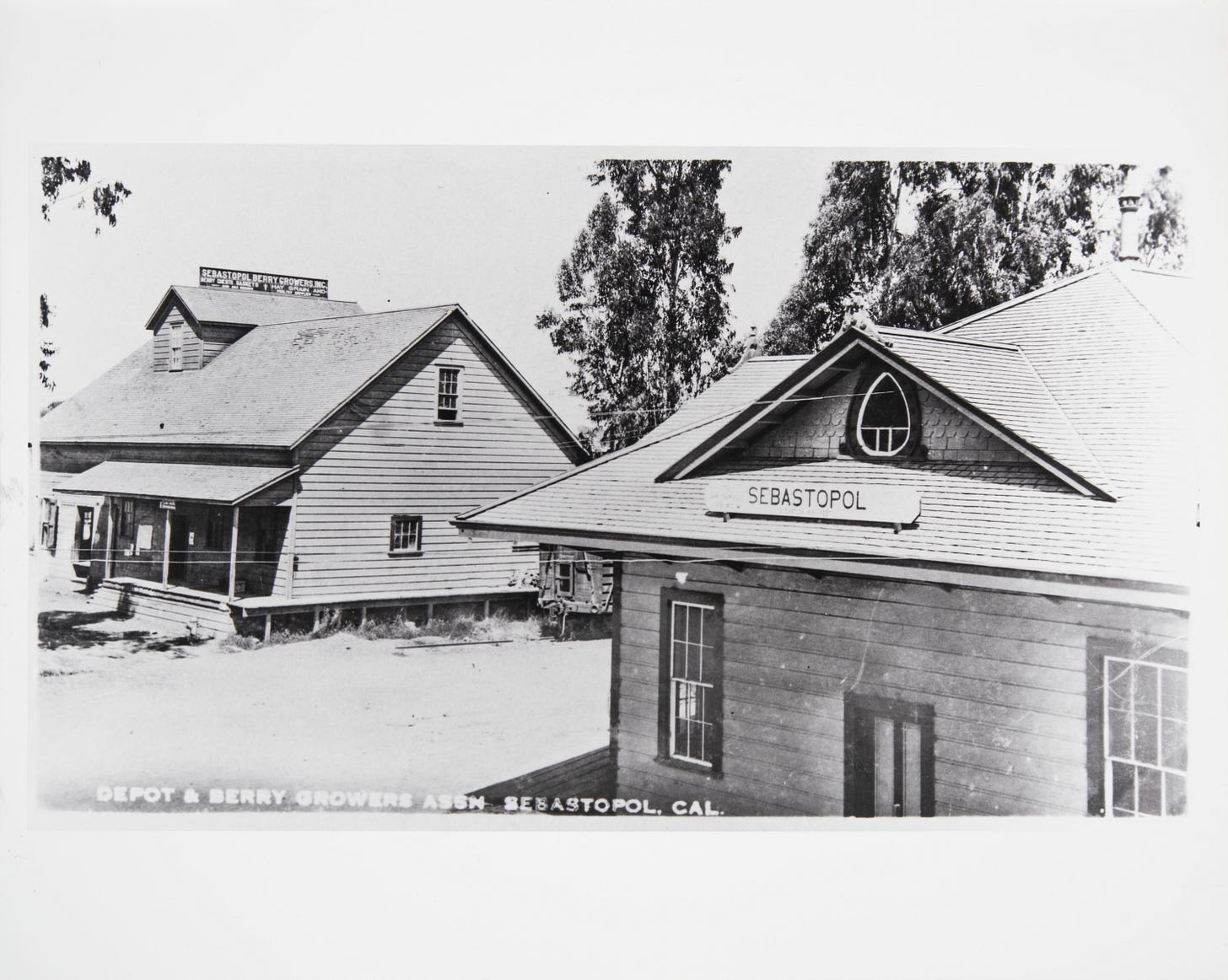

In 1908-09, about twenty growers including Laura E. Barlow filed papers to start what became the Sebastopol Berry Growers Association, an early fruit co-op that sought to raise the price per ton that growers were paid by the canners, and share the cost of equipment needed to process or store the harvest. Gregory wrote: “In order to get the Berry Growers Association established on a firm footing, (Laura Barlow) built a large warehouse at Sebastopol on the steam road.” The building was located somewhere near Brown and Depot street, which is now in The Barlow, and could be near the building that housed The Sebastopol Center for the Arts for some years. One early association building burned down and was rebuilt.

In its heyday, the Berry Growers Association had raised the price per ton from the $20 per ton they were once offered to over $300 a ton for berries shipped fresh and $200 per ton for berries bought by the local canneries. However, by the 1930’s, production that was once as high as 4,000 tons a season dropped to several hundred tons. (Sebastopol Times, January 15, 1932). The Berry Grower’s Association sold off its buildings in 1928 and the association was dissolved in 1932. More and more of the growers including the Barlow Ranch switched to Gravensteins and other apple varieties. The formidable Laura E. Barlow was one of the founders of Sebastopol Apple Growers Union and sat on its board. She lived until 1959.

Burbank’s Himalayan Giant

The trouble is that you can stop farming blackberries but the berries keep growing and spreading on their own.

Many people who see blackberries as a problem point to Luther Burbank for introducing the Himalaya Giant blackberry to Sonoma County in 1885. Burbank acquired the seeds from a trader from India, which is why he called the variety “Himalaya” but the plants were native to Northern Iran and Armenia. The Pacific Northwest blames Burbank for promoting blackberries via seed catalogs in 1890’s, judging from a NPR story, “The Strange, Twisted Story of Seattle’s Blackberries.”

The Himalayan blackberry, from which Burbank created other varieties, is considered an invasive species that is hard to get rid of. Donna Pittman knows. “On the Belmont Terrace area off North Gravenstein, there were berries all around there and when we moved there in 1956, no matter what my dad did, he could not keep them from coming back every year and taking over his vegetable garden.”

“When it gets into an area, it establishes itself and it’s very difficult to eradicate,” says Rachel Spaeth, Garden Curator of the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens in Santa Rosa, referring to the plant’s deep roots, which layer and create shoots when gardeners try cutting them out. Still, she notes that in addition to being an important habitat for fairy shrimp, other native species share credit with Burbank for the berry’s wide reach. “Even though Luther brought it to market, it was really the birds who passed it around, and spread it in our waterways.”

- Leah Griesmann, “How the Mistakenly Named Himalayan Blackberry Became a Summer Tradition.” Baynature.org

The Pacific blackberry is native to California but it is not what most of us find when we are picking wild blackberries late in summer.

In summary, it’s because of the Barlows, Burbank and the birds that we have wild blackberries everywhere that no longer require anyone to farm them, just people to pick them. If you like blackberries, and don’t mind the brambles, then the bounty of each summer’s blackberry mania can be yours to enjoy.

Self-Serve Street Vending

It’s the time of year for farm stands and flower stands to pop up on the road side. I like those that operate on the honor system and sell things like flowers or candy. Like the “The Blooming Cart”, in south Sebastopol. On weekends for the foreseeable future, The Blooming Cart offers locally grown, pesticide-free, fresh-picked flower. It’s self-serve — cash or venmo accepted.

At Gravenstein Station, Eye Candy Chocolatier has “Chocolate to go,” a refrigerated vending machine outside the store owned by City Council member Jill McLewis. You can purchase these confections at any time of day. The instructions are: 1) swipe your card; 2) open the door; 3; remove your selections from the case; 4) close the door. You will be charged for what you have removed. Let’s suppose that the honor system doesn’t work with chocolates.

Week of August 27-September 2

As of September 1, we have 535 paid subscribers to Sebastopol Times. We thank you for your decision to support local news.