Sebastopol gets an in-depth look at the County's homeless services

Last week, the Sebastopol City Council heard a presentation on homeless services from the county's new director of the Department of Health Services

At the last city council meeting, 5th District Supervisor Lynda Hopkins, Nolan Sullivan (Sonoma County’s new director of the Department of Health Services) and Michael Gause (head of the county’s Ending Homelessness team) came to talk to the city council about the county’s homeless services.

The purpose of the meeting was to introduce Sullivan to the council and also to defray a certain friction that’s developed between the county and city over the city’s recent struggles with Elderberry Commons.

Nolan Sullivan was appointed as Sonoma County’s new director of the Department of Health Services four months ago. Before coming to Sonoma County, he worked for the Yolo County Health and Human Services Agency, a county department that combines social services, public health, homeless services and behavioral health. For the last five years, he was director of that department, which has more than 750 employees and oversees a $277 million annual budget. He also served as a city councilmember and a school board trustee in Vacaville, where he spent most of his adult life.

The Sonoma County Department of Health Services has five divisions: Administration; Behavioral Health; Health Policy, Planning & Equity; Homelessness Services; and Public Health. Last week’s presentation dealt only with Homeless Services.

Hopkin’s kicked things off with a brief introduction.

“I really hope that this is the start of a really exciting collaboration between the city and the county, because the fact is, that homelessness is a problem that affects everyone throughout Sonoma County. The unsheltered population do not stay in one place, but rather they cross between jurisdictions, sometimes on a seasonal basis, sometimes based upon responses to law enforcement. There is no such thing as an unhoused person who just stays in one place and only has an impact in one particular area. So that makes it all the more important to coordinate and collaborate across jurisdictional boundaries. The county is the lead agency for unincorporated areas, and it has been traditional that the cities have really taken the lead inside their jurisdictional boundaries. And yet, because of the passage of Measure O and because of the fact that, again, we can't solve this problem in isolation, the county is ready and willing and eager to partner with our city partners to address challenges inside city limits as well.”

She also mentioned that, though she lives just stone’s throw outside the city borders, “Sebastopol is my town, too, and I care deeply about it.”

Interestingly, she seemed to think that the homeless weren’t very visible in Sebastopol.

“You can go through Sebastopol on a daily basis and not even really notice unsheltered people,” she said. “I know that they are there, but it is not nearly as visible and as present as if you drive around pretty much anywhere else in the Bay Area. So I want to acknowledge that. While there is still work to be done, things have certainly improved, and that we are making progress. I look forward to making more progress in coordination with you.”

Sullivan kicked off his presentation by echoing Hopkins’ cross-jurisdictional theme. “Homelessness is not the city’s problem. Homelessness is not the county's problem. Homelessness is also not the state government's problem. It is not the federal government's problem. It is all of our problems, and if we don't work together, we'll never solve this problem,” he said.

The Heart, Soul and Funding Teams

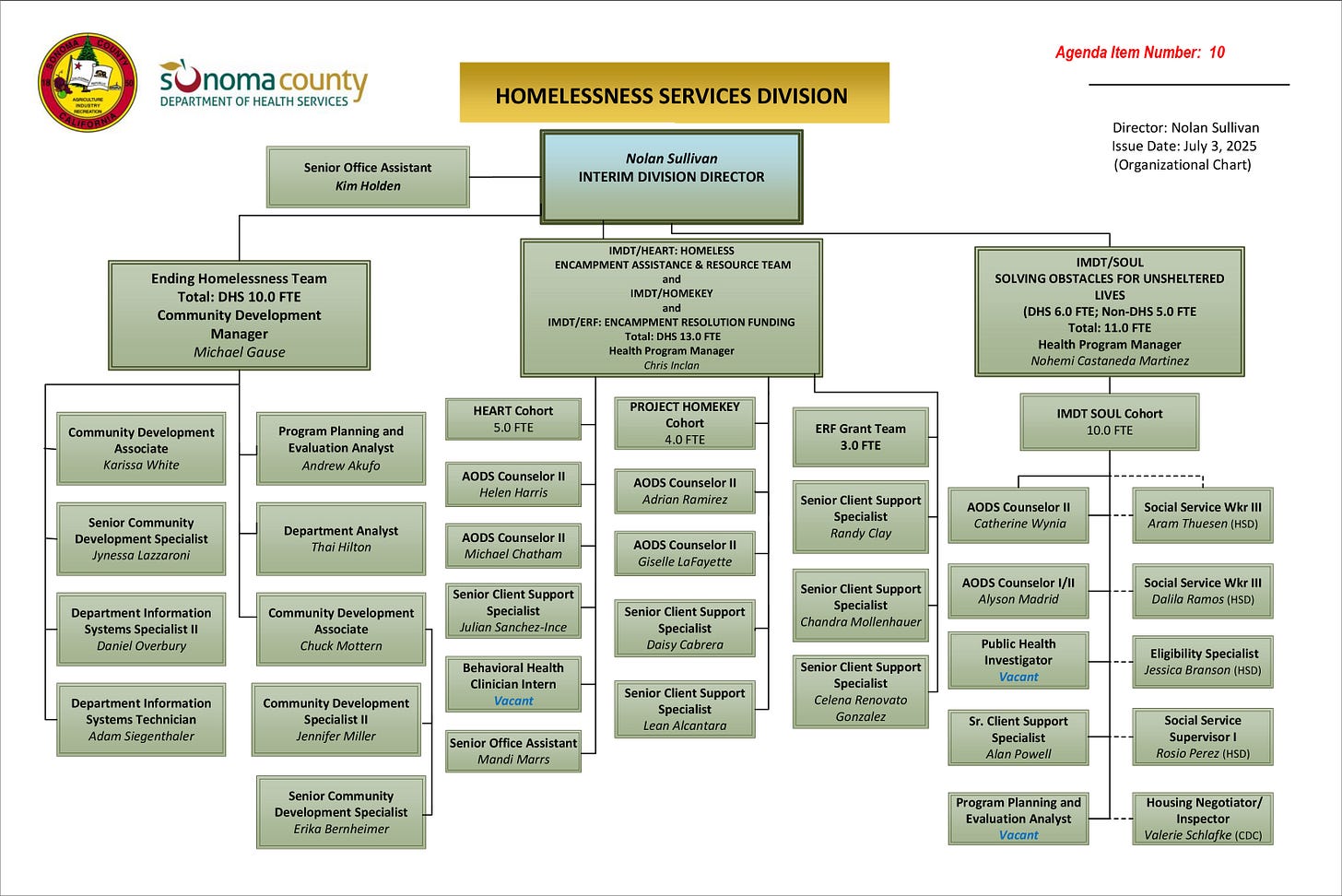

Sullivan noted that the Homelessness Services Division has 30 staff members to serve a county homeless population of roughly 2,000.

The Homelessness Services Division staff is divided into three teams:

The Heart Team reaches out to find homeless people and try to get them into housing and programs. Sullivan said the Heart Team was created to help clear the Joe Rodota Trail homeless encampments and still helps with sheriff’s sweeps. “Generally, they [the Heart Team] are in the unincorporated areas. Sometimes they’re still patrolling the Joe Rodota Trail. And we're going to move into a new phase where maybe we actually start doing a little more city service and service in other areas,” Sullivan said.

The Soul Team provides care and case management to specific clients at County-run sites. “Once you actually find someone and you convince them to go indoors, which is a challenge itself, they have all sorts of barriers, whether it's substance use, it's mental health issues, it's domestic violence, it's getting a copy of their ID, it's connecting with lost family, it's paying off old debts, it's figuring out how to do a housing search,” Sullivan said. “We have a very small team of people that are called the Soul Program, and they are essentially ‘the keepers.’ Their job is to keep people housed and get them into permanent housing.” The Soul Team includes one person on this team that works with ‘transitional age youth,’ a hospital navigator who works with homeless people when they leave local emergency rooms, and then, according to Nolan, “we have a few folks that work in our various shelter facilities."

The Funding Team helps the county patch together funds from federal, state and local government sources, as well as philanthropic sources.

Speaking of Funding…

Sullivan introduce the question of funding for the homeless this way: “It's a mess. There is no guaranteed funding in any given year, and it is a hodgepodgery, depending on the County, the City, the locality you look at.”

Funding for homeless services comes from a patchwork of sources. According to Sullivan’s PowerPoint presentation, much of the funding for homeless services comes through HUD. In 2024, the county received $4.6 million from HUD—$1.2 million went to county services and $3.4 million went out to local nonprofits and community groups dealing with the homeless. The state also provided an additional $6 million for homeless services.

“There is no easy dollar that comes through the system to fund homeless services. It is dozens of grants, funding streams, allocations that come at different times, different amounts, different requirements. It is very, very, very complicated to fund homeless services.”

Though he didn’t mention a total, a quick look at the County budget for Homeless Services for the fiscal year 2025-26 is $24,320,657.

Housing First and Coordinated Entry

Sullivan also addressed the housing policy of “Housing First,” which we’ve dealt with in these pages in regards to Elderberry Commons in Sebastopol.

“Housing first really refers to a homeless intervention approach at the federal level. This has been a requirement from the federal government. This has been the law of the land probably for the last decade. This is also a requirement on many state grants,” Sullivan said.

“What Housing First means is you have to essentially give people access to permanent housing without preconditions like sobriety or participation in treatment programs,” he said. “So we can’t drug test you. We can’t require you to be sober. We can't require that you don’t drink or use legal drugs on the premises. And as a condition of receiving that funding, we have to prioritize that. We don't have a choice.”

“The thought process here is so if you have someone that's living under a bridge and is addicted to substances, the likelihood that they're going to enter a substance abuse program is zero or almost none…So to get people to deal with their issues—the mental health issues or substance use issues—housing them is the first thing that you should do. And I'm not saying I agree or disagree with this. I'm just saying this is the law of the land.”

He noted that this might change under the Trump Administration.

He then went on to discuss the Coordinated Entry System, which the county uses to match people experiencing homelessness to available supportive housing programs.

“Coordinated Entry is essentially a giant funnel,” Sullivan said. “So we have 2,000 homeless people—based on the Point-in-Time Count—and we’ve got roughly 20 beds available in the next month. Who goes first, right? That is the question. Coordinated Entry says you need to take the most vulnerable people first—the people that are elderly, that are disabled, that are the most sick, that are the most mentally ill, because as a society, we value taking care of our most ill, right? This is another law that is mandated. I'm simplifying this to the fullest here, but essentially, we need to screen folks on the basis of vulnerability and the most vulnerable—those are the folks who get permanent supportive housing units first. Those are the folks that get shelter spots first.”

Sullivan then admitted that there’s a problem with this approach. “When you take a large population of folks that have significant mental health issues or substance use issues or medical illnesses, and consolidate them all in a very tight, small square-footage, dense, urban environment, you're going to have some issues and problems…There are ways to maybe do this a little better. But again, if you think about the system: you've got 2,000 people; you're taking the sickest, eldest, most in need, and you're putting them first. It does create a host of problems. So when I see Elderberry in the papers, when I hear people talk about issues they’re seeing down at Elderberry and at a variety of projects, I understand. It’s not that that's by design, but it’s sort of a byproduct how the system works.”

What is the COC (Continuum of Care)?

Sullivan didn’t really describe the COC until late in his presentation, but he referred to it often before that, so I’m moving up the discussion of this federally mandated, independent entity, whose actions are separate from but entwined with the County.

The Continuum of Care (CoC) board has 18 seats and is made up of representatives from cities and the county, nonprofits and other home less service providers, and community members (including current and former homeless people). Its mission, according to Sullivan’s presentation, is “to guide and track individuals and families experiencing homelessness through a comprehensive range of housing and services.”

Funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and some state funds for homelessness are funneled through local COCs to counties and other local organizations. The county provides administrative support for the local COC (which has, confusingly, been renamed Sonoma County Homeless Coalition).

“The COC is a requirement by HUD, a requirement by the state, to receive any of their funding. You have to have this collaborative group—that have all sorts of rules on how they operate and how they spend their money—to receive that funding,” Sullivan said.

“The county is not the COC. I think that's a common misnomer as well. We are the lead agency, but the lead agency is like the administrative assistant to the COC. We don’t guide it, we don’t direct it, we don’t tell it how to vote.”

According to Sullivan’s presentation, CoCs are primarily responsible for creating policy for the following:

Prevention: Helping individuals avoid homelessness in the first place.

Rapid Re-housing: Quickly moving people from homelessness into permanent housing.

Permanent Supportive Housing: Providing long-term housing and support services for individuals with disabilities.

The COC subcontracts out the running of the two main computer systems that are used to track and prioritize the homeless for housing opportunities:

Coordinated Entry: According to the County website, “The Sonoma County Coordinated Entry System is operated by HomeFirst. The Coordinated Entry System is designed to efficiently match people experiencing homelessness to available supportive housing programs. It prioritizes those who are most in need of assistance and provides crucial information that helps communities strategically allocate resources and identify gaps in service.”

HMIS: According to HUD, “HMIS is a local information technology system used to collect client-level data and data on the provision of housing and services to individuals and families at risk of and experiencing homelessness. Each CoC is responsible for selecting an HMIS software solution that complies with HUD's data collection, management, and reporting standards.”

When Sebastopol City Council hired a homeless outreach person from West County Community Services at this same council meeting, it was with the understanding that they would spend most of their time updating the HMIS with information about local homeless people so that they—the homeless people—don’t fall out of the system and become ineligible for housing.

How much does homelessness cost in Sonoma County in a year?

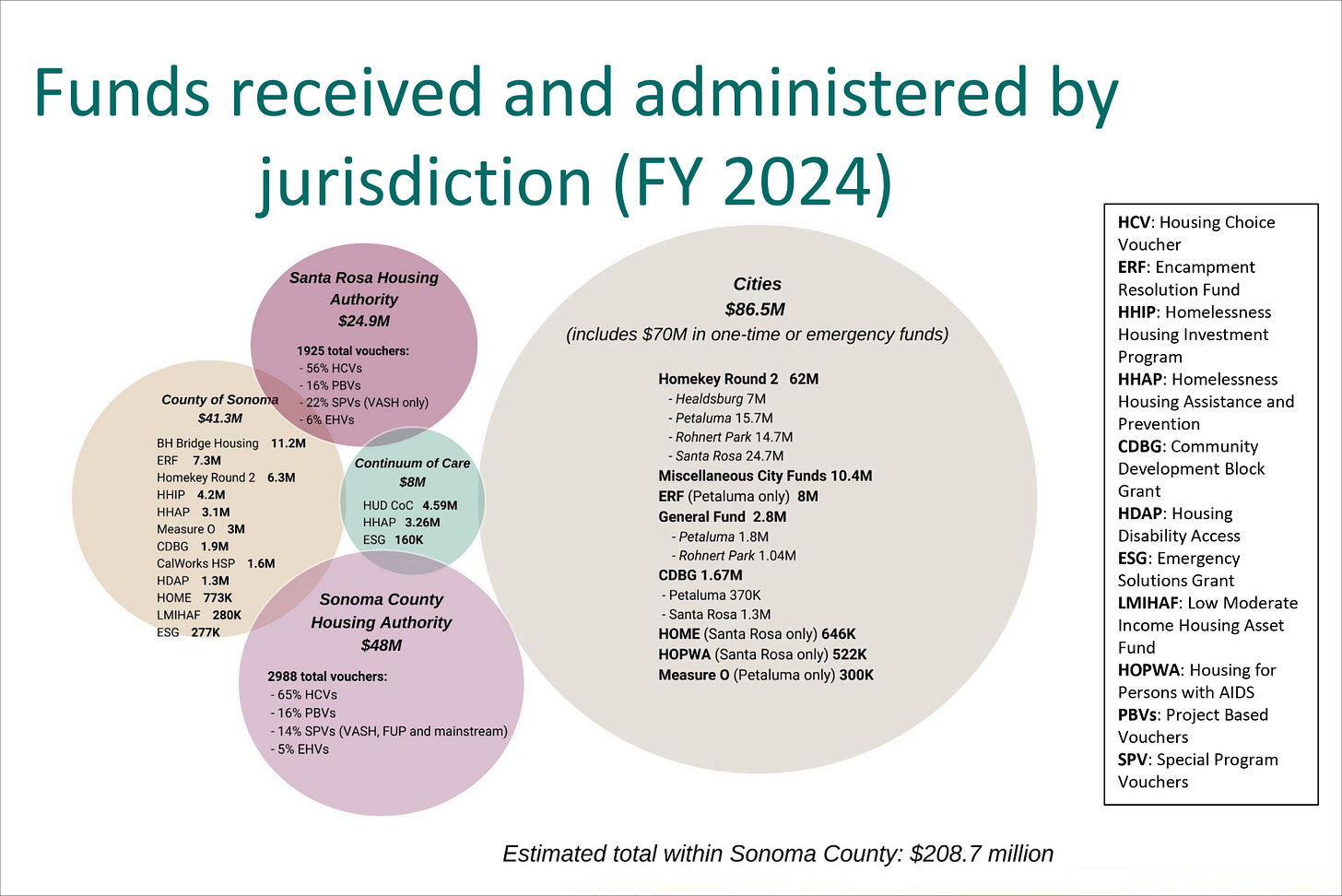

Sullivan then introduced a consultant’s best guess estimate at how much all of the various entities in Sonoma County spend on homeless services in a single year. The answer was $208.7 million a year.

“So if you look there on the upper left hand side, you’ve got Santa Rosa housing authority. So they mainly do vouchers and public support housing. If you look on the lower left there, the kind of brown circle, you've got County of Sonoma, all of our different programs. If you look there at the little green bubble, that's the Continuum of Care, that's those COC and HUD funds that roll through there. If you look at Sonoma County Housing Authority, this is all the folks that are using Section 8 vouchers across the county. And if you look on the right, these are all the investments the cities in Sonoma County are making into homeless services.”

“$210 million is a lot of money, right?,” Sullivan said. “But it comes from a variety of different places, a variety of different programs. It pays for everything from street outreach to permanent supportive housing to vouchers…It is a very complicated web of different programs, funding sources, expenditures and payees. I just wanted to show this slide to really encapsulate just the complexity of funding homeless services.”

Michael Gause, head of the county’s Ending Homeless Program, noted that a lot of the funds in this chart won’t be available going forward.

“A lot of that money was one-time funding,” Gause said, “and that has now gone away. Especially on the city side, there was a lot of COVID funds, a lot of American Rescue Act Program funds. And that is all gone now. So you will see a notable decrease this year and going forward.”

Measure O and an upcoming grant opportunity

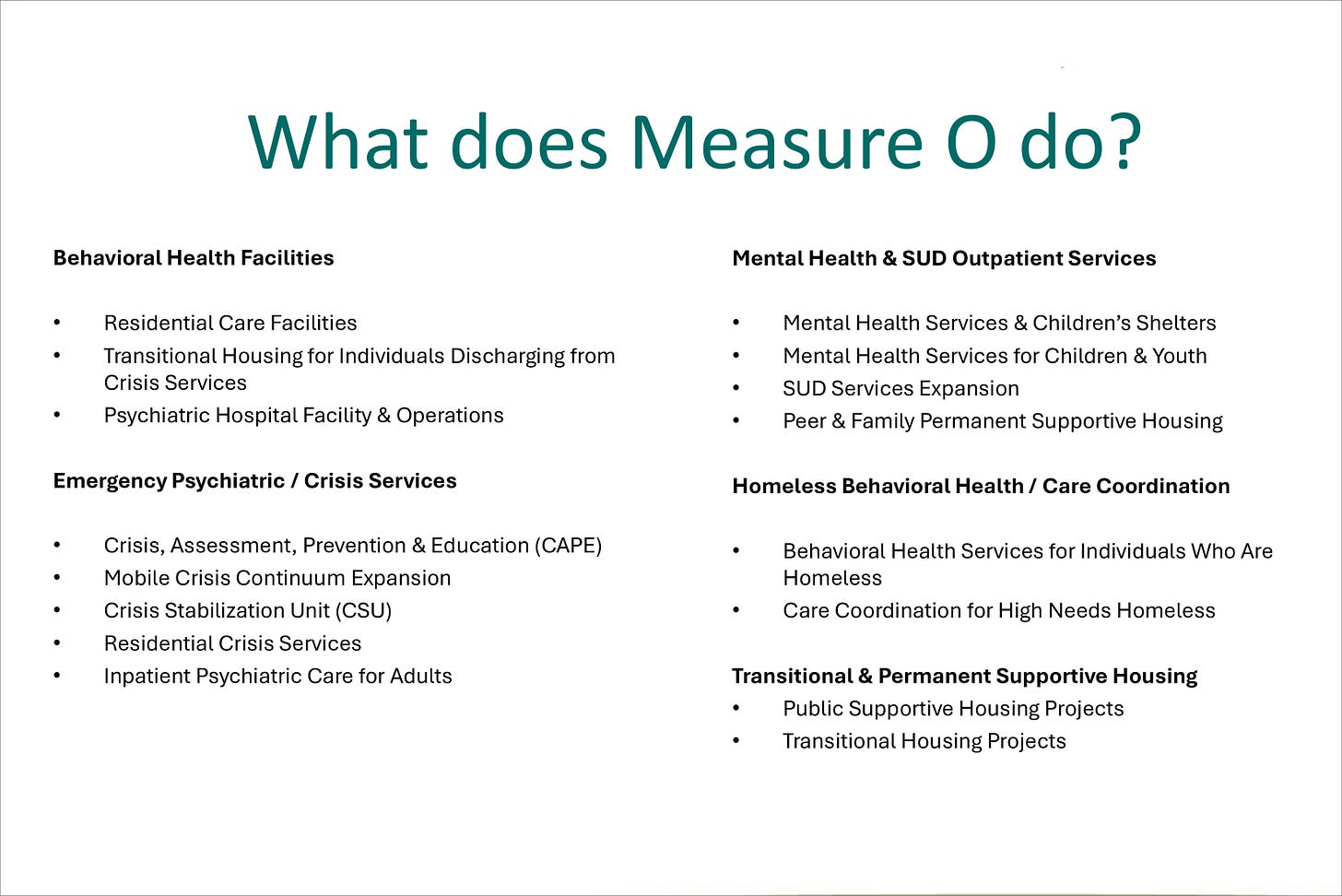

Sullivan then addressed the question of Measure O, which was a voter-approved tax initiative in Sonoma County to fund behavioral health services. It is expected to bring in $25 million a year.

Sullivan gave a breakdown of how that money can be spent.

“The fine print stated that of the proceeds annually, 22% has to be spent on behavioral health facilities, 44% has to be spent on emergency psychiatric and crisis services, 18% has to be spent on mental health and substance use disorder outpatient services. 14% can be spent on homeless behavioral health care coordination. This isn't for housing. This isn't for shelters. This isn't to give the police departments. This is for behavioral health services for folks that are living on the street, and only 2% can be spent on transitional and permanent supportive housing.”

He gave these examples of what Measure O does:

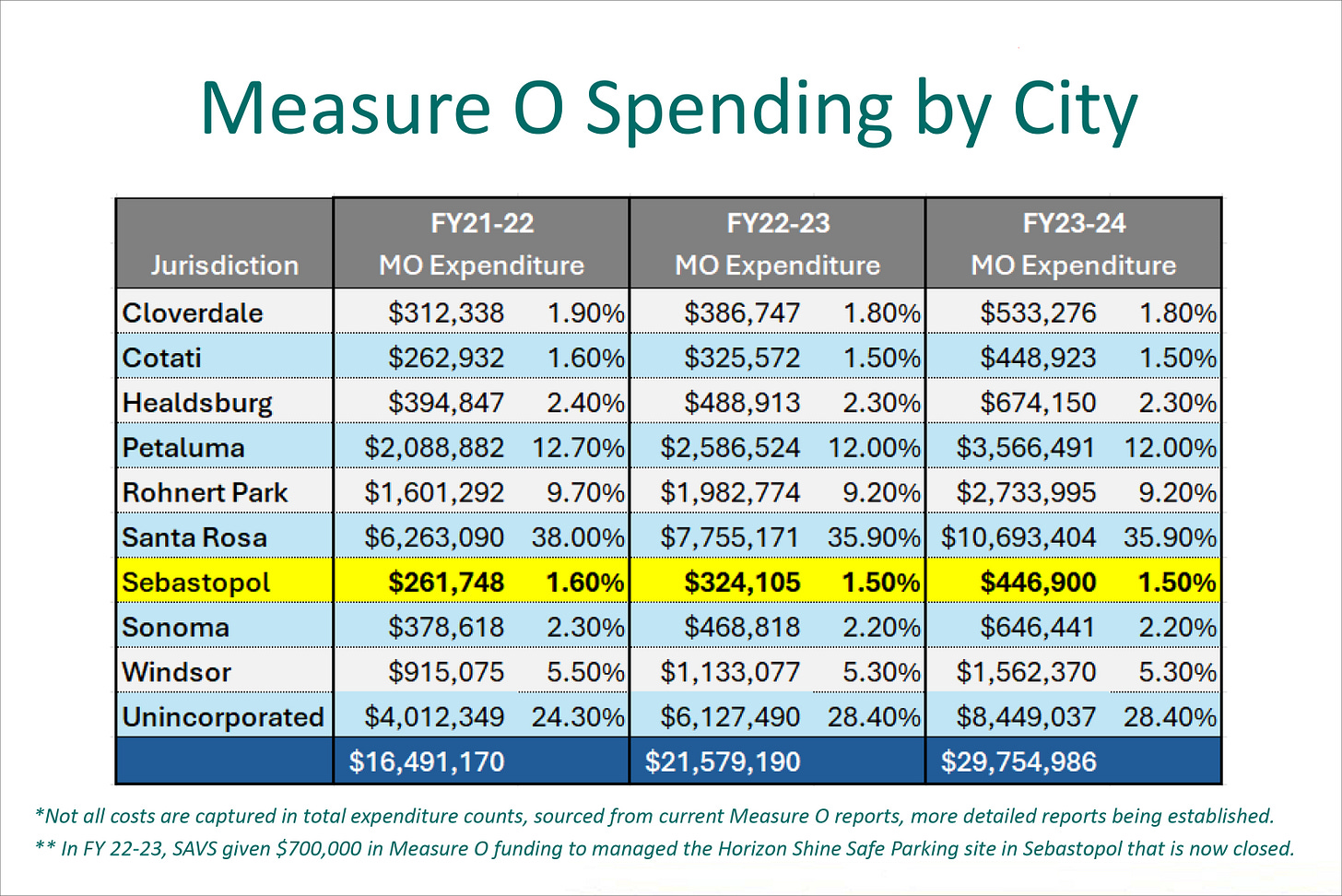

The following chart looks at how Measure O funds are divided among the various cities in Sonoma County.

Sullivan explained that to get Measure O money, cities have to have programs that fit Measure O’s criteria.

“In places like Santa Rosa, for example, Santa Rosa Police Department actually has a Mobile Crisis Team, and so we do give the money to fund some of their police officers that are in the mobile crisis realm.” (Editor’s Note: Mobile Crisis Teams send clinicians rather than or in addition to police to deal with mental health crises.) “We do give them some money to fund clinicians. We do give them some money to fund certain services…there are ways that we can fund cities, but it has to meet the criteria for us to do so.”

Sullivan noted, for example, that in the 2025-26 budget, $5,980,000 in Measure O funding went to support Mobile Crisis programs across the county (in Santa Rosa, Petaluma, Cotati, Rohnert Park and at Sonoma State University).

Sulllivan also announced that the county was releasing a NOFA (Notice of Funding Availability) for $10,000,000 in Measure O Funds. Cities, nonprofits and service providers offering homelessness and mental health services can apply for Measure O funds if they have program that fits the criteria. (See the NOFA here.)

Although this funding opportunity is only for existing programs, not new programs, he noted that if the Sebastopol Police Department wanted to create a Mobile Response Unit, that would be allowed because the Sebastopol Police Department is an established, not a new, entity.

Counting the unhoused

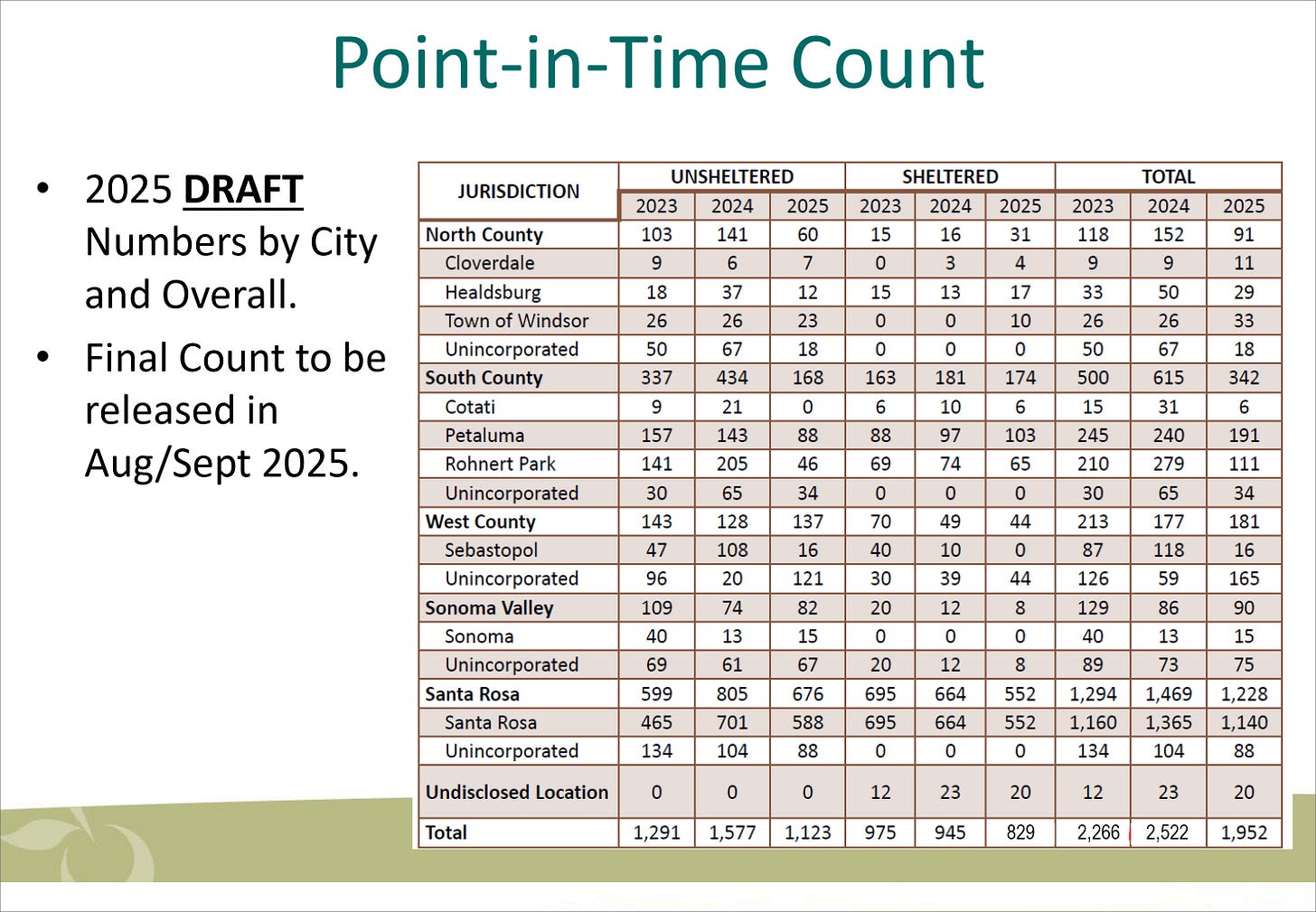

The county keeps track of the number of homeless people in the county in two ways: the annual Point-in-Time Count and the By Names List (BNL).

“The way that we count homeless folks—and this sounds a little bit ridiculous, but it's true. Once a year, we literally go out and hand count people. So we train a bunch of volunteers, a bunch of professional folks—I'm sure some of you in this room have done it—and we literally go out and do a hand census,” Sullivan said. “And that is our best guess at how many folks that are living in our community are homeless and whether in sheltered or unsheltered. Unsheltered obviously means we see them on the street, under a bridge, by a creek or in a car. Sheltered means they're in a shelter facility or being sheltered temporarily in permanent supportive housing.”

The draft Point-in-Time Count for Sebastopol lists the number of homeless individuals for 2025 at 16.

“I know it probably doesn't feel that way for some of you folks,” Sullivan said. “But homelessness is also migratory. So you'll notice that in the unincorporated area around Sebastopol, it's a little bigger than that—it’s at 181. So folks meander. They migrate here and there.”

Point-in-time counts, which are required by HUD, are also useful in tracking the number of homeless people over time. Sullivan said there’s been a dramatic drop in the number of homeless people over time—down from 4,700 in 2011 to just 1,900 in 2025. “So that’s some serious progress. It’s been cut in half,” he said. “I know it doesn’t always feel that way. I'm not trying to diminish the needs that we have, but the county has made some significant progress.”

The second way the county keeps track of how many homeless people there are is the By Names List.

“Essentially the By Names List is a system in which we use law enforcement, shelter operators, folks that know the homeless, to really verify that the names are in fact a homeless person from that community,” he said. “It’s a sort of a double check, a fact check and it oftentimes helps us have a kind of a better snapshot of the homeless community in a certain city.

The number of homeless individuals on the By Names List for 2025 is 1,850.

In closing, Sullivan gave a final plea for taking a coordinated, multi-jurisdictional approach to homelessness in Sonoma County.

“I know that there are folks here tonight who are frustrated about Elderberry or they're frustrated about downtown,” he said. “We will never solve homelessness working in one city, with one person at a time. We’ve got to look at an entire system, we've got to leverage and share. I know it's easy for me to say that when your business is being vandalized, or when you've got someone sleeping on your porch, or while you're hearing people screaming at night. But if we all work together, across the cities, the county and the nonprofits, because of the limited resources, we will never make a dent in this. The cities and counties that collaborate and work well together are going to be the ones that thrive, and the cities and counties that fight or dig in or sue each other or blame each other, you're just going to have the same problem that you've had the last couple of years. We have to solve this together.”

1) Thank you Laura for this well organized/written piece. 2) It seems to me the best people we've got are doing the best they can - and they sound well organized and quite competent 3) There, but for the grace of ____, go I.

County budget $28MM or $14,000 for each homeless person. Overall spending $208MM last year $104,000 per homeless person. Throw in another $25MM in Measure O funding or $20,800 per homeless person with "mental health issues". After some searching I could not find what % of homeless with mental health/addiction issues accept treatment but suspect is a pretty low number which raises questions about what measure O money is being spent on.

The $1MM in measure O money spent in Sebastopol during the last three years raises even more questions. The table heading says "Spending by City". When confronted with the fact that no one in the city was aware of $1million dollars in mental health services, someone said it was some sort of allocation not actual spend. There was also a reference to $700,000 spending on Horizon Shine but is closed prior to most of the funds shown in the table. The notice that we have to apply for next year's measure O funding and only have 2 days to do it was fun. Maybe, the county did not get the message we don't have a team of people in the city working on this. We barely have anyone working on anything at this point with vacancies. Mary Gourley is doing great work but there are limits.

You didn't mention the 278 MST mental health calls in the city that again no one was aware of. Many were made together with law enforcement. Even with the mayor's call for our own mental health team, it is surprising that no one was aware that the MST was in Sebastopol almost every day last year?

The overall message was the county has amassed funding and infrastructure to address homeless issues with multidisciplinary teams. Sebastopol has a 1/2 time outreach coordinator that does busywork for the COE system. It seemed like Mr. Sullivan got the message. He seemed open to the idea that the homeless in Sebastopol are also the homeless in West County and the County needs to cross into our little city. Supervisor Hopkins frequently comments on her willingness to help the city but there was never any follow through, perhaps because she does not "see any homeless in Sebastopol".

They are invisible if you don't want to see them. They are sleeping by the city hall and library, at the side door of Rite Aid, in the alcove by the boot maker and in cars in the Safeway parking lot. There are a growing number of motorhomes and trailers in the shopping centers. One motorhome was just towed off of Morris street. Drug dealing is quite visible in the Safeway parking lot among those sleeping in cars. With school reopened, our high school students will be a potential new market for the drug dealer there. A recent fire in the Laguna was due to a homeless camp.