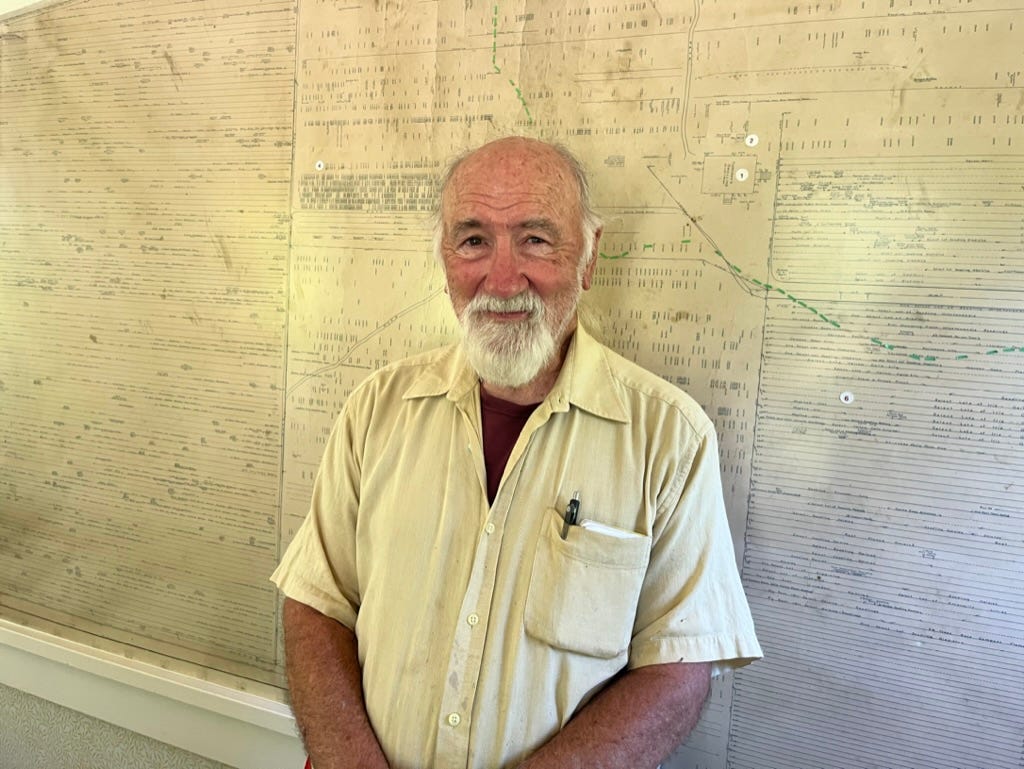

Press Fest is this Saturday at the Luther Burbank Experiment Farm from 10 to 2pm. You’ll be able to use an antique apple press or a more modern electric one to make delicious juice from local apples. This week, I had the opportunity to talk to Steve Fowler who was curator at the Luther Burbank Experiment Farm from 1989 until 2010.

Fowler is the one person who knows as much about the farm’s past as well as its present as a historical museum and active farm. For this conversation, we sat in the cottage at a large table. I pressed record and really just listened to Steve talk. He has a wonderful deep voice, which has also served him well in various roles as an actor. He’s been part of the Cemetery Walk for 15 years, playing local notables such as Jasper O’Farrell and Willard Libby. (We’ll cover the Cemetery Walk next week.). See Steve and others involved in the farm at Press Fest on Saturday.

Transcript: Steve Fowler on the Luther Burbank Experiment Farm

Dale: From 1989 until 2010, Steve Fowler was the curator at the Luther Burbank Experiment Farm in Sebastopol. We met this week at the cottage on the farm and sat around a large table surrounded by all kinds of Burbank memorabilia. I pressed record and really just listened to Steve talk about Luther Burbank, the experiment farm, and the efforts to save the farm and continue its work in the present.

Steve: I'm Steve Fowler. I'm a landscape gardener by trade. I'm retired since 2010. And when I retired, I gave up the job of curator of the Burbank Farm, a position I'd had since 1989.

I had an intimate knowledge of just about every square foot of the Burbank Experiment Farm in Sebastopol.

Dale: How big is the farm today?

Steve: I'm going to say two and a half acres. It expanded and contracted depending on negotiations with the city and also with the Burbank Heights Corporation that did senior housing next door.

And at first was very resentful of the farm. Don Dowd and I didn't see eye to eye in those days because I was the representative of the farm and the only person who was ever over here, at first. I've seen a lot of water go under the bridge, so to speak.

Dale: What was the size of the experiment farm in Luther Burbank's day?

Steve: It was 15 acres. We always say 15 acres. And if you look behind you, you'll see a map that represents those 15 acres. There was a time when he owned part of what is now the cemetery and the story is that he gave it up because there were too many gophers. He was trying to grow gladiolus up there and they were just killing him.

That's an original map. It shows the, literally, tens of thousands of plants that were here at that time. It was completely fenced because Burbank did not want anybody messing around over here. There was no plant patent law, and his experiments could be easily stolen, particularly when they got to the point where they were about ready to be introduced. It's also said that he searched the pockets of his employees to make sure they weren't carrying any seeds or twigs. Horticulture is so portable because of the fact that you can make cuttings from just about anything and of course seeds are almost invisible.

He charged, and we have right here a ticket, $10 for a quarter of an hour if you wanted to come visit him here at the farm. And in those days... I think that ticket is dated 1916. That's funny to say that. It's such a bygone century. But in 1916, ten bucks would buy you a suit of clothes, I'm sure.

Maybe pay the rent on an apartment for a month or something like that. It was a lot. It was prohibitive and that was the idea. Because he really wanted to be left alone over here. If he wanted to show off, he would do it over in Santa Rosa at his house, he had a nice house, he had a glass greenhouse, a wife.

Two wives, actually. One was a big mistake. She hated town; she thought he was an important person and they would ride around town in a gilded chariot or something. He was just gone all the time. He was working 14 hours a day and just cared about his plants.

So that didn't last, but he did marry his assistant, Elizabeth toward the end of his life, and that was apparently a love match. A very deep love match.

Dale: When did Burbank stop coming to the farm?

Steve: He stopped coming here, I think, in about 1924-25. He died in 1926. But he had stopped working at the farm for a couple of years. I think he was even trying to sell the place. I don't think he did because his wife, Elizabeth, installed an apple orchard after he died.

So large parts of what he had done was was destroyed. But there was this one little section where the cottage we were sitting in was, and there was a barn, and there was a sort of, it wasn't suitable, maybe suitable for apartments, and there were lots of gnarly old trees. Some local historians, activists, and Mel Davis, who was then the city manager contrived to create a condition in the use permit that this be set aside.

That was the late 70s. I'm not sure of the exact times of all those maneuverings.

After he died, there was still tremendous interest in the farm. The Kyle family moved into this house and actually remodeled it so that they could raise their girls here. I think there were a couple of Kyle daughters and at least one son. They all lived here, but the well had gone dry in 1906 when the earthquake struck and the house was knocked off its foundations and had to be rebuilt.

So this is the second version of this cottage and it dates to the 1908, something like that. Also Stanford University was interested and then there was a nursery in Missouri, Starks nursery that bought all of it, the rights to all of his plants. They had someone living here who was working here, whose job was to find experiments that still had some promise, and then remove them to their nursery in Missouri, where they would rename them, or name them, and then sell them to the public. Unfortunately, the microclimates in Missouri were so different that most of it didn't make the cut.

Luther never had much of a relationship with the scientific community. Because he didn't work with the same principles that, for instance, Mendel or the geneticists of the time.

He worked from instinct. I think he had parapsychological abilities. I'm sure he did, as a matter of fact, but I can't prove it. It's the sort of thing. How could he go down a line of plants, kick over every one except the one that he thought had promise? And this would be years before that plant turned into the Shasta Daisy, or the Santa Rosa Plum, or whatever. The plants talked to him, or he talked to them. He understood and he had an extraordinary ability.

And he never drank or smoked, so his senses were sharp. I wish I had his senses. Because the sense of smell is completely gone from my body. Years of cigarette smoking took care of that, and my eyes are going. My ears are still okay, but... Plants don't actually make much noise, you but but he had to, he was very sensitive to them. Yeah, so he could bypass all the stages that scientists have to go through in order to establish-- Mendel, he didn't even know about Mendel, actually. Mendel had done his work, but he believed in the idea of inherited characteristics. So he believed that a plant could acquire characteristics during its lifetime that could be handed on to the offspring independently of the sexual reproduction.

Now, of course that isn't true, but what we know now is that he was able to activate genes in the plant pool that otherwise would never be expressed by the exquisite care that he gave the plants. When a plant was given that kind of care, just like a person, they began to express things in their flowers and their growth that otherwise would never appear.

That was the acquired characteristic that seemed like a genetic impossibility. But it was really a matter of just treatment, how the plant was treated. Lamarck. It was called the Lamarckian Fallacy. And so there's a lot more truth to it we know now than it was given credit for at the time.

The historical society was incorporated as a non profit specifically to take on the farm project. Renee Felciano. By the time that I got on board in 78, I think it was already, the farm was certainly preserved. And some work had been done. A landscape plan had been prepared by EcoView, an outfit out of Napa.

But the fact of the matter was that there was no money to install, to do anything. The city didn't wanna spend any money and the Burbank Heights people disliked the idea because they still owned the property and they were liable for anything that happened over here in the way of an accident. They could see suits coming at 'em from right and left. So that's why they opposed the whole development of the farm at that time.

There was an architect oh, God, John Banks? I have an old brain. It takes a while to churn out names. Yeah, but he and Renee were a team. They started a program that that gave awards and did surveys of historic buildings that were being either properly maintained or remodeled in an appropriate fashion, in keeping with the original style.

Which is this cottage. The wallpaper, the doors, all the brass handles, everything is historically accurate. John Hughes. I knew that name would come to me. So many of these people are not with us anymore. John Hughes is not. Renee Felciano just died a couple years ago. It became important, in order to preserve the farm from future development, that it be recognized by the historic American Building Survey. And that's on the wall over there in brass. This is officially recognized as historical, meaning that it cannot be sold.

Dale: Talk about some of the things that are happening on the farm now. You have a new fenced- in area.

Steve: That has everything to do with our new curator, we call him a curator. And that's a holdover from the idea that this place is a museum. A curator is someone who cares for historical or for museum artifacts. In my day, that's all I did.

There were some trees here that were historically interesting and so the idea was to keep them alive. And that meant cutting down oak trees, for instance. And it meant removing vast quantities of broom and poison oak and blackberries. I didn't do most of that work. Circuit Riders was engaged to do it.

It was a war on poverty idea. LBJ. They had a headquarters up in Windsor. And they brought a crew down here, and they must have worked for weeks, and they took almost all of the, maybe some valuable plants, who knows. Lisa Bush was running it, and she was very well educated.

Everybody was wondering, what's left? And a guy named Bob Hornback was rummaging around here, and he was a botanist and he has become a historical botanist. Very important character. But that's to explain the word curator.

Jamie Self, who is the current curator, and has been for, what, three years now? Three years. Brought in a whole lot of new energy and new ideas. And he took it to the next level, which was to actually start propagating, maybe eventually even hybridizing. That meant you had to control the deer population. That meant fencing off a good section of the farm for that purpose. And that was a controversial thing. I think we all agree it was a good idea. So Jamie who had experience already with managing volunteers from Esalen Institute and who is a landscape contractor with all the tools and expertise that go with that.

I was a landscape contractor too, but I'm from the dark ages. I did plans with a pen and a pencil. I did all my billing myself, with checks and invoices. Nowadays that's all happening online. Jamie's got that under control, but he's really brought a lot.

Alex McLean was here for 10 years, and he did a lot; he was a building contractor. So he did a lot of repairs on this building, the cottage. He completely remodeled the nursery and turned it into a modern, productive facility.

Aaron Sheffield turned out to have a talent for getting grants. If you have willing people and you have someone who can write grants and you put them together, stuff happens.

That also was not true for most of my career here. Of course I started from zero. There were no paths. There was no electricity. There was no sprinkler system; there was nothing. We took it to the point where there was a new barn. That was built in '97 with help from the Pellini family. And they helped us get a tractor. And that meant we could put in better paths. And it went on from there. I would say that the farm is no longer what it was thought to be, which was a museum. It's now become a working facility that produces lots and lots of nursery plants. It's growing crops like potatoes and tomatoes and flowering plants.

It has a tree nursery, where lots of trees are being grown. These are all on display this coming weekend on Saturday, the 16th. From 10 o'clock on? 10 to 2. So we're showing off this weekend. That's called the Press Fest. We're going to be displaying our antique apple press beautifully redone. It's a hand crank. Oh, kids love that. You get that flywheel going and it just practically drags you around in a circle .

But there's an electric one too, and the Slow Food people operate that on weekends and produce a lot of juice. It's a great public service and it's another sideline for the farm.