The Movement and the 'Madman'

Documentary shown at Rialto elucidates how the anti-war protests changed Nixon and America

To be a prisoner of the moment is one of humanity’s greatest proclivities.

For example, over the past decade, many have argued the following in absolute confidence: This is the most divided America has ever been.

Though perhaps the language of Donald Trump and the silos of the internet create novel variations on social division, the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a U.S. being torn apart.

“We're not a country of historians,” a laughing Stephen Talbot told me.

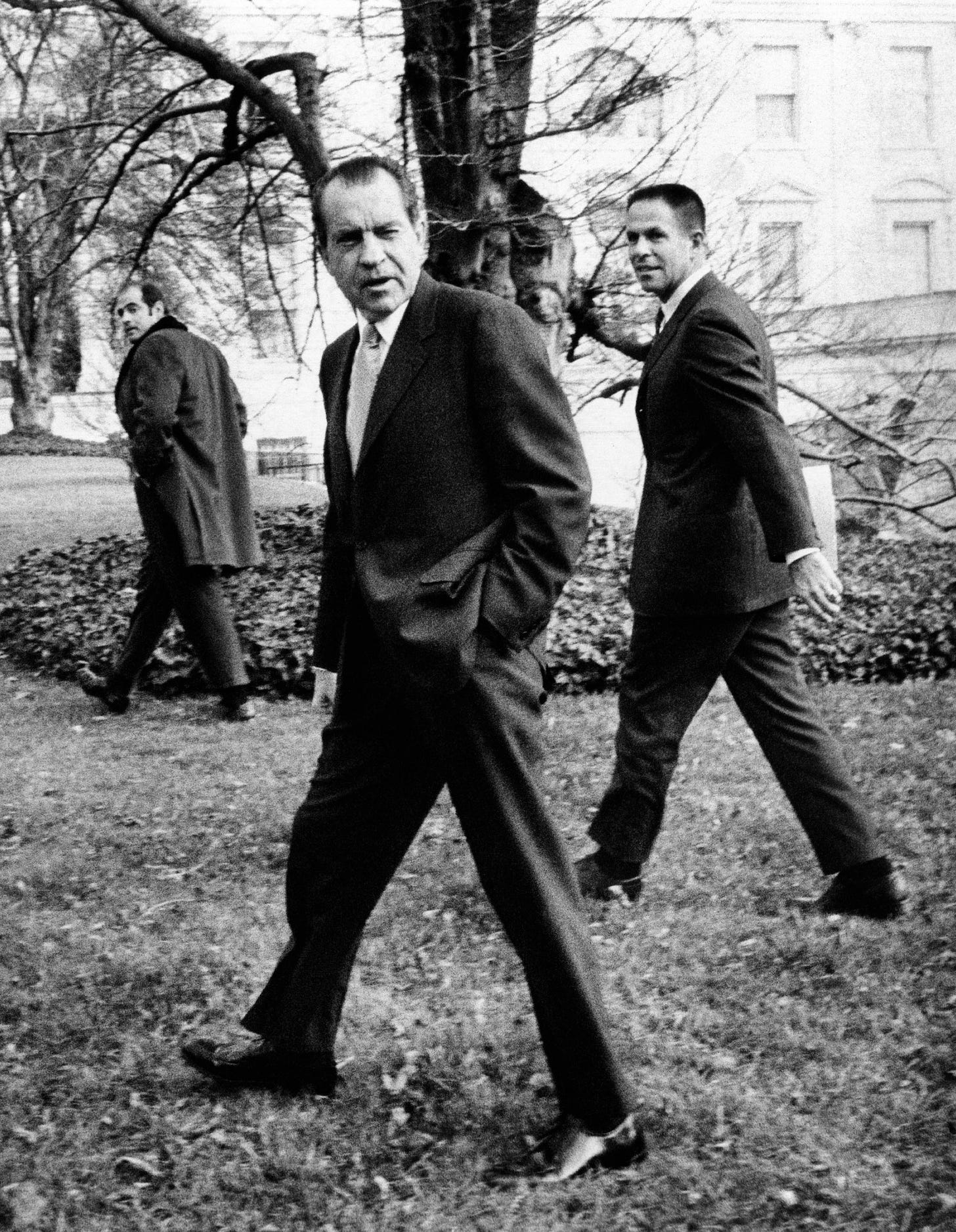

Talbot directed “The Movement and the ‘Madman’,” a documentary on President Richard Nixon and the anti-war movement that was shown at a Northern California Public Media event at Rialto Cinemas on Wednesday.

“It’s hard to compare, but I would say the polarization was as bad then as it is now,” he added. “There was a big battle over civil rights, and then there was Vietnam, and those two things changed everything.”

When Talbot asked the Sebastopol audience for a showing of who participated in the anti-Vietnam War protests of 1969—the first year of Nixon’s presidency and the time frame in which the film is set—over half raised their hands.

Many claps ensued. Defenders of Nixon were nowhere to be found.

During the Q&A section of the event, audience members highlighted how their generation’s protests were even more ambitious and disruptive than those taking place on American campuses or streets today.

“At its best and at its largest, the anti-war movement in the United States was the biggest protest movement in the history of the country,” Talbot would declare with certainty.

This was the point of the film, he said, to inform people who weren’t around back then—or those who have since forgotten—just how remarkable these protests were.

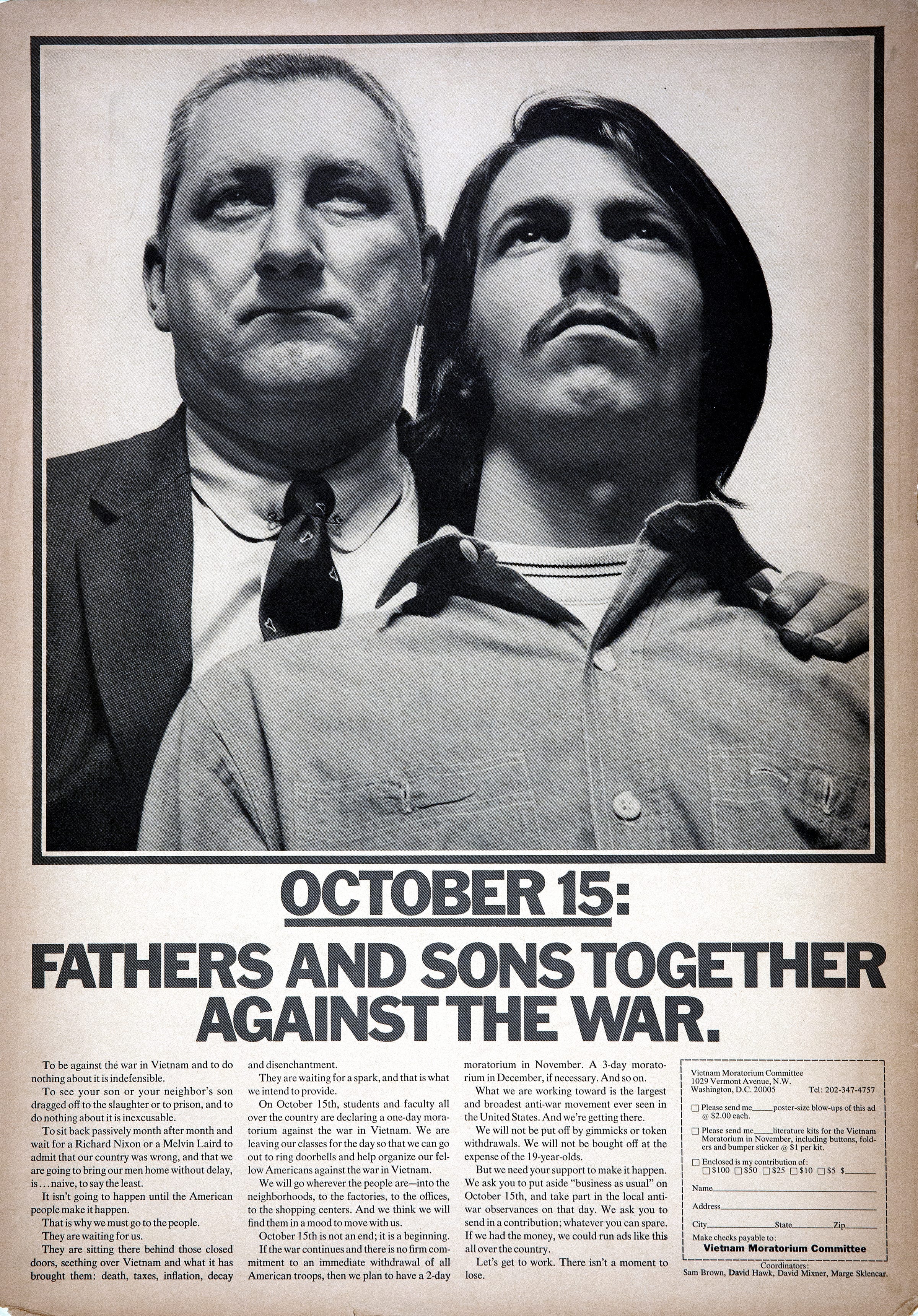

Not only was it yippies who were refusing the draft, but it was a coalition that included Democratic and Republican congressmen, housewives, religious sects and labor unions.

“Any time there's a mass movement, you're always going to have divisions and arguments and so forth,” Talbot said. “What helps pull things together is if there's a large center to a movement that has a lot of optimism, a lot of hope. I think that's what motivates change—a feeling that you know you can succeed.”

And, lest we forget, these guys were hardcore.

Take the March Against Death, which was highlighted in Talbot’s film, as case in point.

Over the course of 39 consecutive hours starting November 13, 1969, around 50,000 people marched throughout Washington D.C., each protestor carrying a candle and a sign with the name of a US serviceman or civilian killed, or a Vietnamese village wrecked by the war.

“It took between three and four hours to walk the distance from Arlington, past the White House, over to the Capitol grounds,” says Susan Miller, a co-coordinator of the March Against Death, in the film. “It was not a short walk. And it was freezing. I have never been so cold in my entire life.”

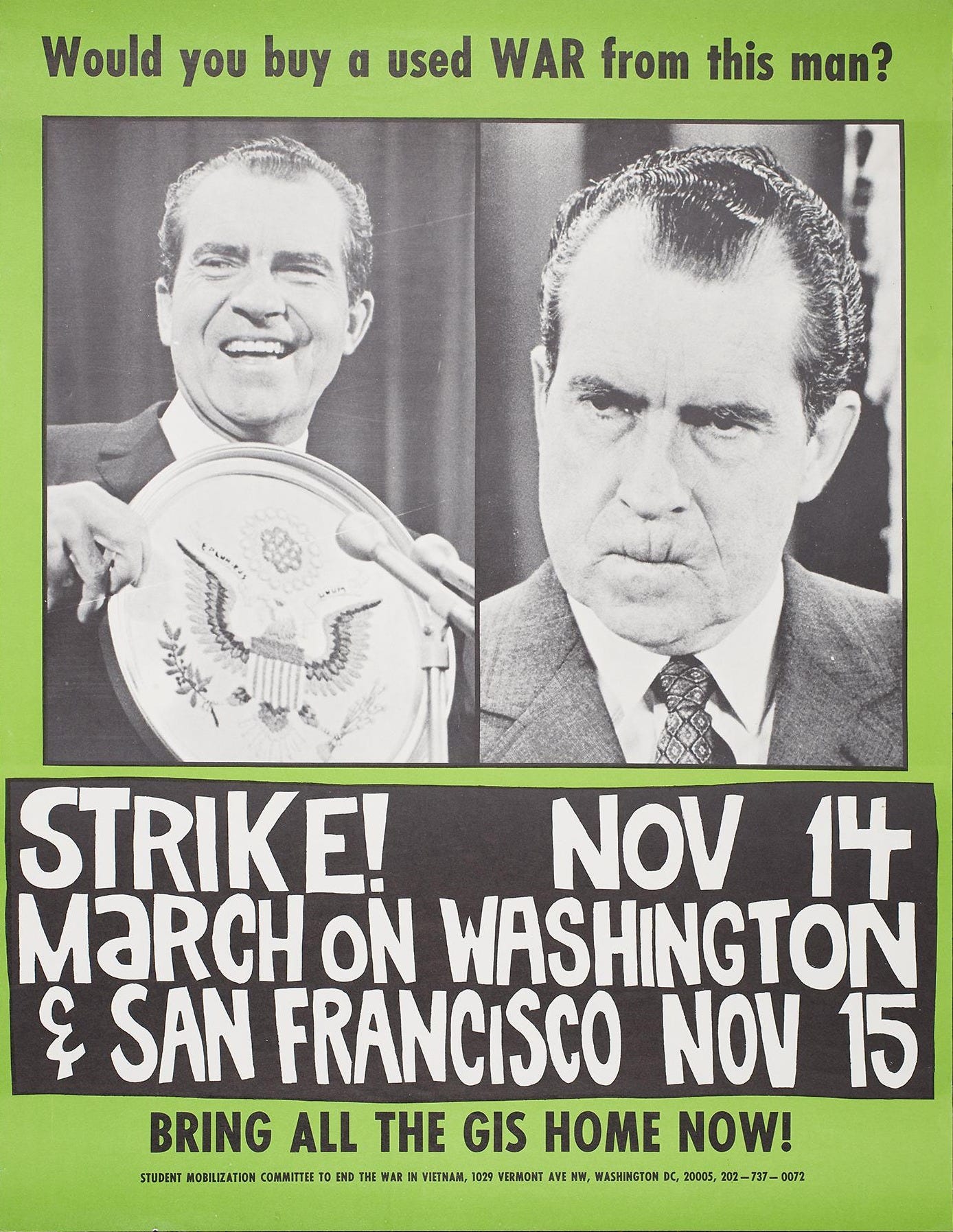

Even as Nixon stated in his “silent majority” November 3 televised speech that he would be wrong to allow “the policy of this nation to be dictated by the minority,” behind closed doors, the documentary shows, he was growing more and more threatened by the size and audacity of the protests.

According to historian Christian Appy, who also speaks in the film, “At one point during the candlelight ceremony out in front of the White House, Nixon turned to his aides and says, ‘Can’t we get some helicopters to fly over that demonstration and blow out the candles?’ Which shows you the level to which he was concerned about it.”

And concerned were his supporters, who led him to victory again in 1972.

“As a backlash to the anti-war demonstrations of the Fall of 1969, many powerful people around the country who supported the war rallied around Nixon,” Appy said. “He began to really successfully turn the debates around Vietnam into a debate around patriotism and cast anti-war activists as unpatriotic, playing a kind of divisive politics that the Nixon administration was really expert at doing.”

It is the tension between the growing anti-war movement—which, in historian Carolyn Eisenberg’s words, had already “destroyed Lyndon Johnson’s presidency”—and the foreign policy decisions of Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, that serves as the spine of Talbot’s documentary.

Nixon’s first days in office were full with serious discussion of a major escalation in Vietnam, even flirting with the idea of nuclear weapons. It would not just be America’s War in Vietnam, but “Nixon’s War.”

“Nixon wanted to end the war quickly,” said Tom Wells, the writer of “The War Within: America’s Battle over Vietnam,” in the film. “The way he hoped to do that was by threatening the North Vietnamese with a major escalation of the war. And he had this idea that somehow he could convince the North Vietnamese that he was capable of anything—to blow them to smithereens.”

The documentary reaches its climax on November 14 and 15, 1969, during the second “Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam,” which featured mass protests in both San Francisco (as many as 250,000 people) and D.C. (as many as 500,000 people).

Before these marches, the film posits, the anti-war *movement* was somewhat separate from Americans who were simply against the war. No longer.

“Here in San Francisco, Moratorium Day protestors assembled early for the seven-mile march through downtown San Francisco to Golden Gate Park,” said reporter Mel Wax during a KQED broadcast on November 15. “Estimates of the crowd size vary, but all agree it was the largest peace demonstration ever held in the western United States, and it was peaceful.”

While the Fall of ‘69 protests didn’t immediately inspire Nixon to pull a significant number of troops out of Vietnam or to stop bombing countries in Southeast Asia, they made it clear that a grand escalation of the war, a.k.a. Nixon’s “madman strategy” (alternatively known as “peace with honor”), wouldn’t fly with the American people.

“If he dramatically escalated the war, the country might explode,” said Wells in the film.

Thus Nixon held back.

But, according to Talbot and many others, including “the most trusted man in America,” Walter Cronkite, the war was not simply immoral by 1969, but it was also more or less unwinnable.

“There was no way you could really defeat the Vietnamese without literally destroying [Vietnam],” Talbot said.

So why wasn’t Nixon preparing to pull out entirely?

“Nixon wildly overestimated the influence that the Russians and the Chinese had on [North Vietnam President] Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese,” says Talbot. “They were supplying the weapons, and they were very important allies. But, had Moscow suddenly said, ‘We’re cutting you off, and you’ve got to end this war,’ the Vietnamese were going to keep fighting. Flash forward a few years later, and what happens? There’s a border war between Vietnam and China late in the ’70s. So this whole idea that everything was black and white—communist or not communist—the whole Cold War paradigm that was imposed, missed the reality of what was going on. It was primarily a nationalist campaign to have an independent country without any foreign control.”

“Nixon did not want to be known as the president that had lost the war,” Talbot continued. “Lyndon Johnson had the same impulse. The other thing is that Nixon and Kissinger were smart in a lot of ways. They knew a lot about foreign policy, and they loved foreign policy. They were Machiavellian, and they kept it very close in the administration. The Secretary of State at the time, William Rogers, was totally sidelined. Nixon and Kissinger ran foreign policy entirely, and they liked this idea of a grand bargain with the world. It’s like playing a chess game. These are the big powers, and we control the world, and we move the pieces around. Their loss is our gain, and vice versa.”

Since many of the interviews for the film were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, sources were recorded alone, often in studios. According to Talbot, that made it so the movement leaders and government officials could immerse themselves in their memories as they recalled them.

Talbot and his team also pivoted away from including video of the interviews as you would normally expect in a documentary.

Instead, they layered audio recordings of the interviews with archival footage that Talbot and his team had recovered.

This, Talbot said, was supposed to make the film like “time travel.”

As songs like “Chimes Of Freedom” by Bob Dylan, “Bring Them Home” by Pete Seeger, “Give Peace a Chance” by John Lennon and “Carry it On” by Judy Collins rang throughout the theater, the viewer was permanently transported into the year 1969.

Far between sundown’s finish an’ midnight’s broken toll

We ducked inside the doorway, thunder crashing

As majestic bells of bolts struck shadows in the sounds

Seeming to be the chimes of freedom flashing

-Chimes of Freedom, Bob Dylan

There's a man by my side walking

There's a voice within me talking

There's a word that needs a saying

Carry it on, carry it on

-Carry it On, Judy Collins

From setting the stage of the Watergate scandal to eventually ending the war, the film makes a point to note that the effects of this period on American history were not all known at the time. Nixon’s own legacy was also not cemented.

“When Nixon is inaugurated and Henry Kissinger hired, the names on that long black Wall in Washington were only half as long as they ended up being,” said former Kissinger aide Roger Morris at the end of the film. “The price of Nixon’s ‘peace with honor’ would be enormous. And I think in the end unforgivable.”

Says anti-war activist Frank Joyce, also in the closing scenes of the film: “When I talk to young activists today, one of the points I make is you will not know in the moment the real impact of what you are doing, and you may not know it in a week. You may not know it in a month. You may not know it in a decade, but you are having an impact. It does matter.”

Talbot, who filmed the protests of 1969 as a college student, has made a career of directing PBS documentaries such as these. Now well into his seventies, Talbot wonders if this one will be his last.

“If I want to go out on something, I'm glad I went out with this film,” he says. “I'll put it that way.”

Watch Chapter 1 of the film below on YouTube.

You can login to Kanopy with your library card to watch the whole thing here: kanopy.com/en/sonomalibrary. You can also watch the whole thing on Amazon Prime or pbs.org.

I really like reading whatever Ezra Wallach writes. Keep him.

The teaching of hate and power is a multigenerational issue. The protesters of today have the kids of tomorrow and the cycle repeats. Morality/ethics needs a bit of altruism, but greed and short term gains dominate the media, and we’re not a nation with collective memory. Hence the power of this film to remind, the few that care. It wouldn’t get a corporate sponsor to be on MSM….

Well written essay. Thank you