The Unknown Thiebaud

Explore Wayne Thiebaud's prints at Sebastopol Center for the Arts. The opening reception for the exhibition is today, Saturday, Jan. 10, 4 pm to 6 pm

How is it possible that the best exhibitions at Sebastopol Center for the Arts just keep getting better and better? “The Unknown Thiebaud: Passionate Printmaker,” curated by SebArts patron and passionate volunteer Alan Porter, is a case in point.

The show is an exploration of artist Wayne Thiebaud’s lifelong fascination with printmaking—a passion that in the public mind has been eclipsed by his colorful oil paintings. Half of the prints in this exhibit come from Heather Stone, the daughter of Thiebaud’s longtime dealer, Allan Stone, who represented Thiebaud at his New York gallery for 45 years.

The exhibit is organized thematically, not chronologically—with each section highlighting common themes (basic shapes, repetition, angle and perspective) that Thiebaud worked with throughout his life.

I had the privilege of walking around the exhibition with Alan Porter yesterday. I considered turning his erudite lecture into a quick piece of journalism but thought that would do damage to its richness and depth. Rather, as an experiment, I thought you could join us on our stroll around the gallery. Almost all of the text below is Alan speaking. Comments from me are rendered in bold italics, and actions are shown in italics in brackets.

So tell me about the exhibit.

We all know Thiebaud from the lush oil paintings for which he’s understandably famous. But he was also totally passionate about printmaking, and the prints are rarely seen because when a museum wants a retrospective, they want it to be a blockbuster, and all they show are oils. So in the recent exhibition at the Legion of Honor, there was not a single print, not a single drawing even; it was all oil painting.

[He gestured around the SebArts gallery.]

These are things that mostly never see the light of day. They’re in people’s homes. They’re rarely exhibited, and we had an opportunity to really dive into that, because we have access to a fairly significant collection that’s here in Sonoma County. His dealer for 45 years was Allan Stone in New York, and one of Allan Stone’s daughters lives here locally. So we were able to borrow a little less than half of what’s here from her, and then shamelessly cabbage the rest of it together from a lot of other sources.

How does that work? Like I know you know people, but…

I call everyone I can think of, and people that I never even have heard of, and just say, ‘Do you have something or know someone who does?’ And there was a pretty significant period of time where I wasn’t coming up with anything more, and then all of a sudden, a lot of things fell into place. This is really a tribute to the generosity of the owners of these works of art who really want to share them with a wider public.

I loved the detail about Thiebaud making his first print as a teenager—was it with his mother’s car?

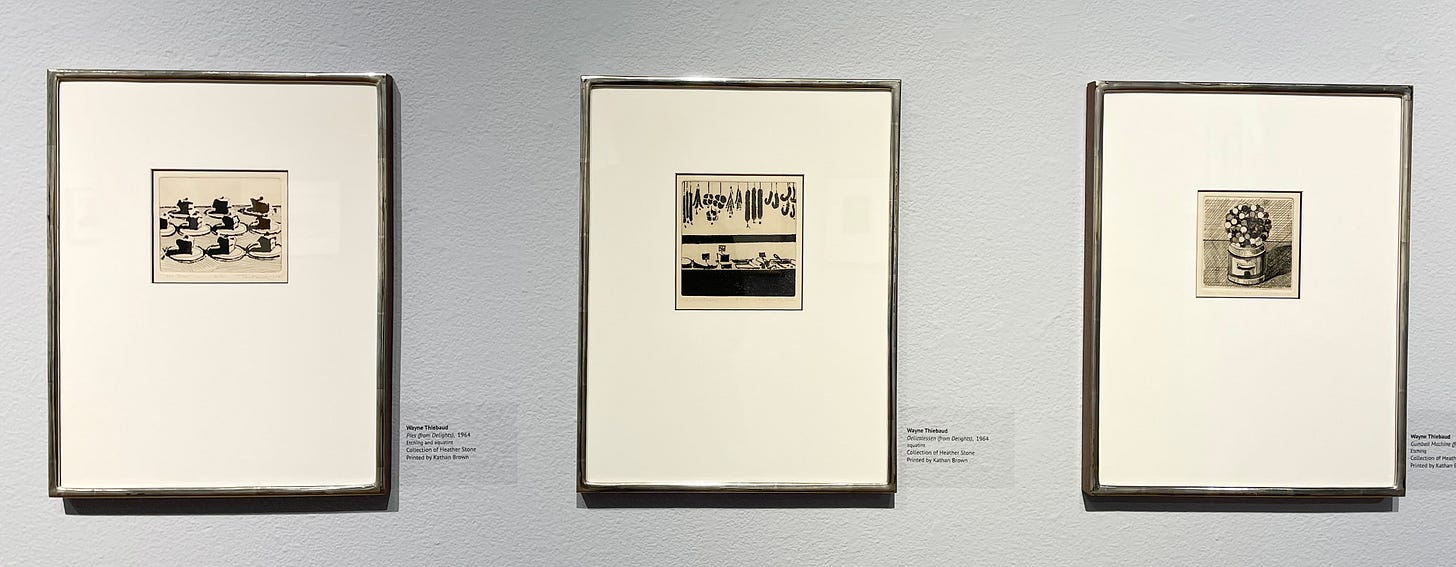

No, his mother’s ringer washing machine. We have a seven-decade period of prints that we’re showing here. So he returned to printmaking constantly, over and over and over again.

So this one [on the left in the set of three above] was made in 1951, and this print [on the far right] was made when he was 99 years old. And he still has that incredibly sure hand, which is just incredible to have maintained that and still have the vision of what it is you want to do that late in your life. He lived to 101—a ripe old age. People ask, “Where did you get all the quotes for the exhibit?” And I said, “Well, when you live that long, you have an opportunity to give a lot of interviews. So I had a lot of things to pick from.”

[We stopped in front of a piece of Thiebaud’s from 1957.]

In the early 50s, in the mid 50s, he was still very much in the thrall of abstract expressionism, but he couldn’t really let go of representation completely, right?

Yes, it’s an abstracted cityscape.

He went to New York, and specifically wanted to meet William De Kooning, one of his idols. And de Kooning famously told him, ‘You’re a really good painter, but your work looks like 100 other people. Go home and figure out what it is you want to paint. And don’t make the art world your subject matter.’ So he went home and relied on the long-term advice of Paul Cezanne to return to basic shapes, circles, triangles, squares, rectangles. And he was sitting there with a triangle and a circle, and suddenly it looked like a piece of pie.

And he said, ‘Oh, this is sort of Americana, you know. This is an everyday object. Let’s focus on this.’ He kept working with that.

There is a whole section in the exhibit dealing with the concept of the basic shapes. What’s interesting is that Cezanne was interested in basic shapes because he was looking for a way to push toward abstraction and away from realism. Thiebaud was doing the opposite. He was looking for a way to leave abstraction and return to representation.

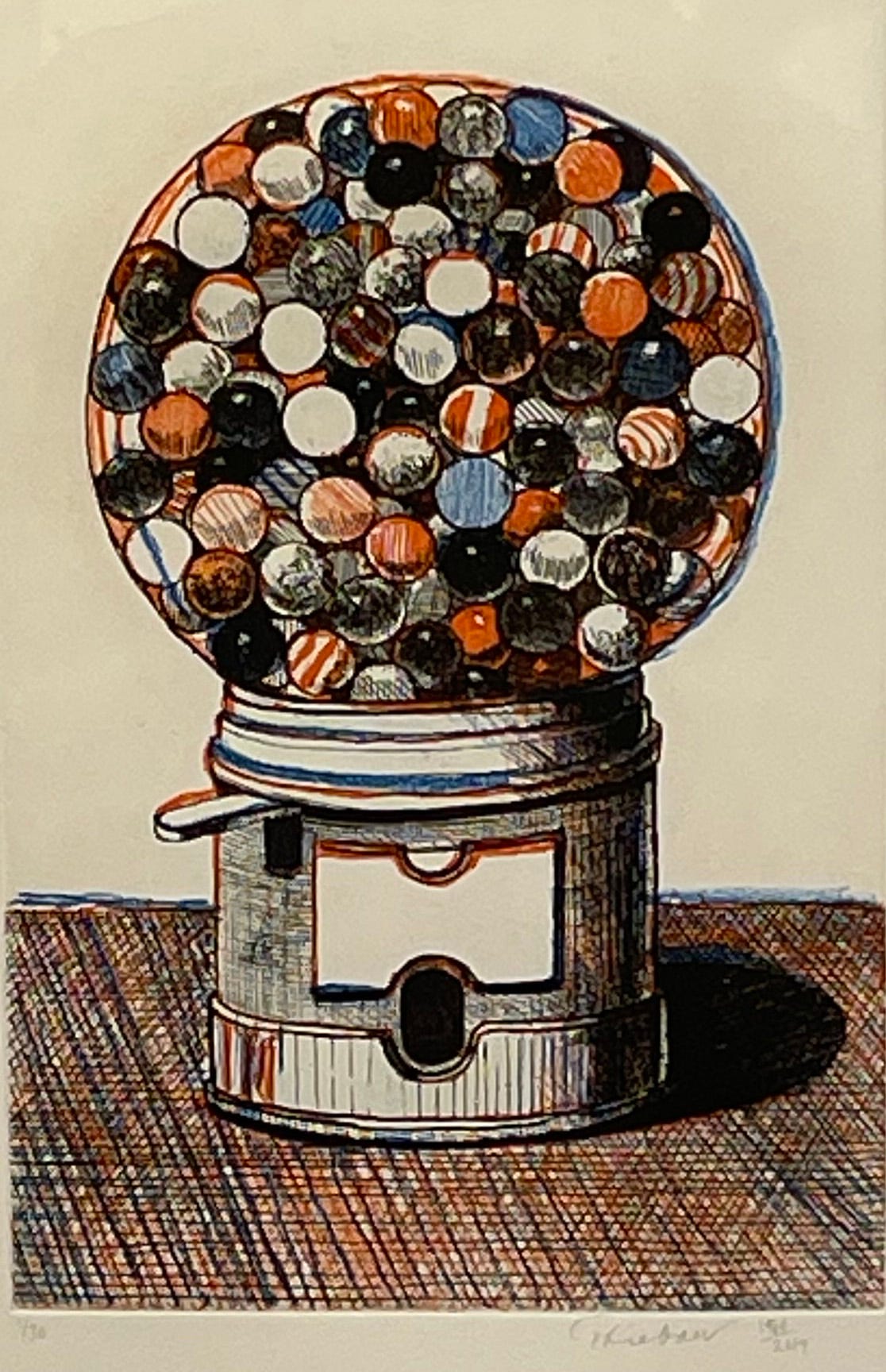

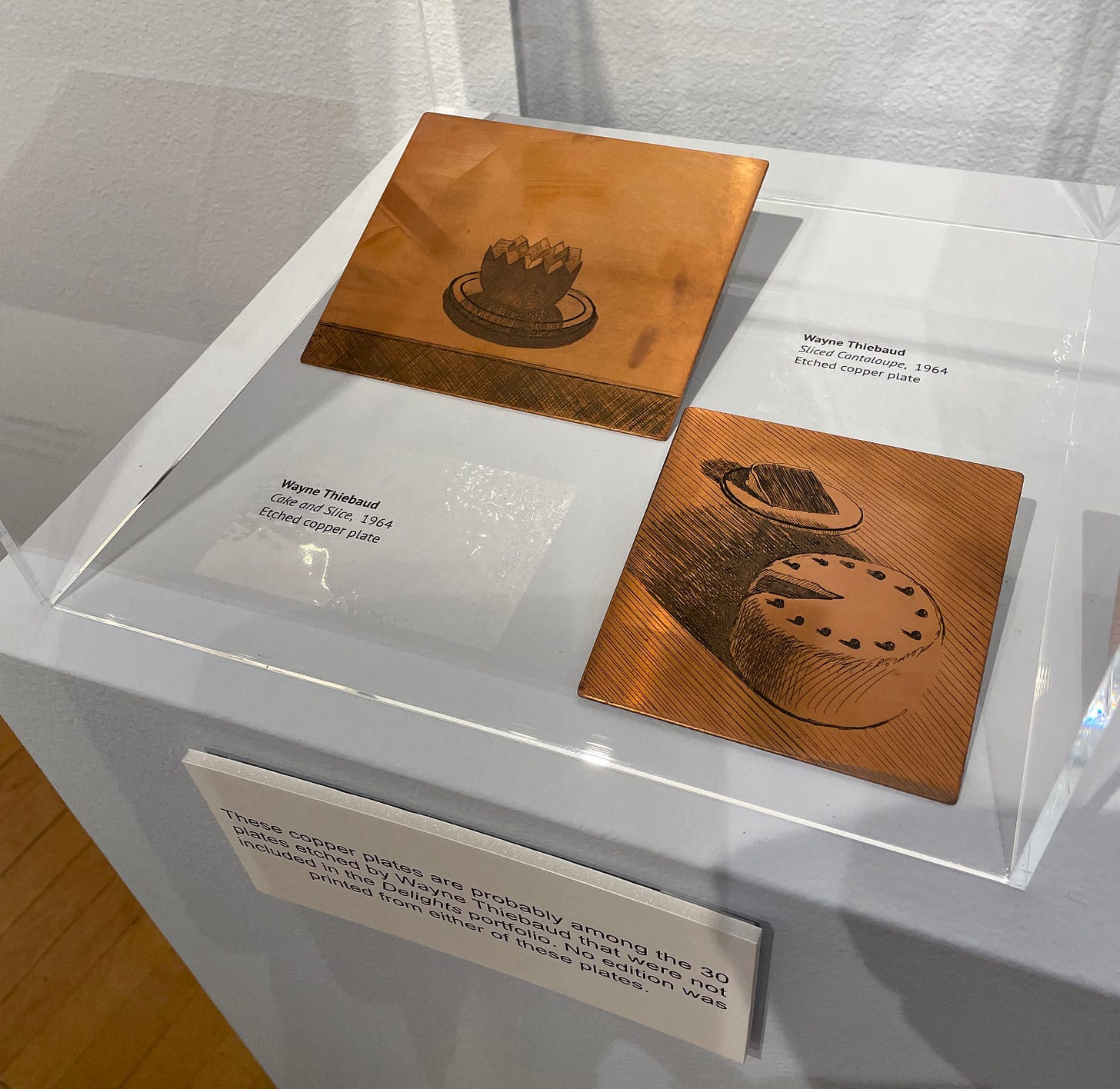

This first grouping here [below] is a very influential group of prints that he made at the newly established Crown Point Press in San Francisco, which is a legend. Kathan Brown had seen some of his work, and she wanted him to come and do a portfolio, and he ended up making 47 copper plates, of which 17 were printed and put in the portfolio, “Delights.” We have two of the copper plates that were printed. These are from the collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation in Sacramento.

When Thiebaud first went to Kathan Brown’s workshop to start making prints, he pulled out some snapshots of paintings that he had done. She was livid. She said, “This is supposed to be about original works of art, and you’re not making a one-to-one copy of something you’ve already painted.”

Thiebaud said, famously, “Changing anything changes everything.” And he’s fascinated by just how a two-degree shift, or a four-degree shift, or the angle of something changes your perspective of the entire thing. He wanted to know whether something in black and white could have the strength of a lushly painted oil painting.

He used printmaking a lot to experiment, to test new ground, new territory that he was interested in, and he looked at every sort of artwork that he created as “I’m setting a problem for myself, and I’m going to try to solve it. And if I shift the composition by moving something in the background, how does that shadow change the entire artwork?”

Another thing we got from the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation is a set of monotypes. Monotypes are a unique work of art but done in a printing format. So you take the glass plate or the copper plate, and you paint on it and then print from it. You get one print, so it’s not an edition. You haven’t created a matrix that holds ink in the copper plate. Sometimes you print a second time, if there’s any residual ink, and you get what’s called a ghost.

[Around the corner from the monotypes is a section dedicated to Thiebaud’s dealer, Allan Stone.]

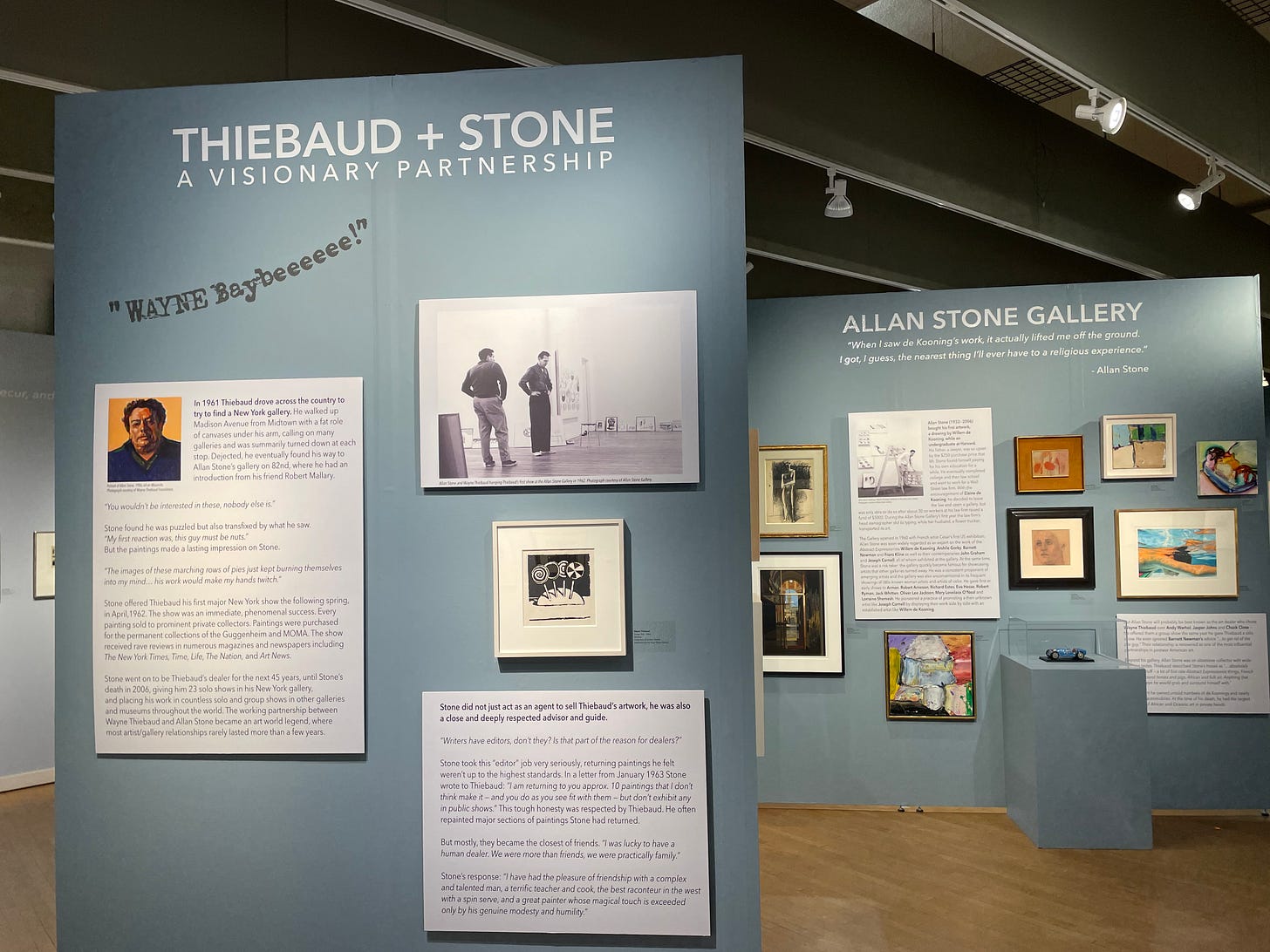

Thiebaud was trying to find a gallery in New York, and he came with a big roll of paintings and went to endless galleries and was summarily rejected by everyone. He had an introduction to Allan Stone, and Allan Stone wasn’t sure what he was looking at at first, and said, ‘I’m kind of mystified by this,’ but they really resonated overnight, and he agreed to give Thibault a one person show. That show in 1962 was an instantaneous, phenomenal success. Every painting sold. The Guggenheim bought one, MoMA bought one, and Thiebaud’s career was off and running.

And then we have another wall here that is artists that were also represented by Allan Stone. Allan and Thiebaud became the absolute, very best of friends. Unlike most situations in the art world where an artist and gallery are rarely together more than a few years before a successful artist is poached by a bigger gallery, or they get mad at each other, or whatever. Allan represented him exclusively for 45 years and gave him 23 one-person shows.

There’s a great phrase: “What is the purpose of a dealer?” And Thibault responded, “Well, writers have editors.” And Allan Stone took that really seriously. He famously would roll back up a bunch of canvases and send them back to Wayne and say, “These don’t make it. You need to either get rid of them or rework them.” And if you saw the Legion of Honor show, there were a number of paintings that would say, like, 1972/2006, and that would be a canvas that he came and revisited and reworked.

So his first 1962 show with Allan Stone—would that be considered in the early period of pop art?

[Porter looked aghast.] He’s not a pop artist. What is interesting is there’s an expression that “he has been misunderstood into fame.” He painted everyday objects which were common among the pop artists, right? And he was included in a show in Pasadena that Walter Hopps curated, that was called “New Painting of Common Objects.” That exhibition more or less defined pop art, and so he was often wrongly slotted in with pop artists—and he got this huge lift from being associated with pop art. But whereas pop art is usually flat representations, commercial printing, screen prints, things that would look like comic books, Thiebaud’s work was about embracing this luxury of what paint can do and how a brush stroke can create this incredible tactile experience—totally the opposite. It was like he’s embracing these objects rather than cynically looking at them and making comments about our consumer culture.

Thiebaud thought he was creating a sort of a new American still life. You can go back and look at something else over here about the influence of the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi, who is not well known in the public, but his work is revered by most artists. He painted the same 35-40 vessels on a shelf for, like, 40 years, just moving them around and making different connections with them, changing the composition, changing the shadow. And his paintings are like a visual spa day. I mean, you just feel like everything in the world is just fine when you look at Morandi’s work. And Thiebaud, famously, would take a Morandi reproduction, put it next to his canvas and see what he could do to try to make his work more like Morandi’s—to capture that feel of everyday objects.

You know, when we think of still lifes, we tend to go back to the 18th century and earlier—the French and Dutch still lifes, in particular, that were just big tables filled with vegetables and fruit and flowers and usually dead animals hanging in the background. And Thiebaud just said, you know, we shouldn’t be afraid of our everyday objects. They’re not going to tattle on us, and that’s what he painted much of his career.

And then there are his landscapes.

In 1971 or ’72, he bought a house on Petrero Hill, and he started this whole new body of work that, particularly for the cityscapes, they look like they have been collapsed through a telephoto lens; everything is happening in the same frame.

And what is interesting about these is we have progress prints. So printing isn’t just about creating one plate and being done with it. Frequently, there are multiple plates that are being used and a lot of artistic decisions that are being made in consultation with a master printer about, ‘Well, what happens if I do this? What if I change the background to pink? What if I…’

These show some of the decision points along the way, and in these two progress prints [in the painting on the right] you notice at the very end he cut off the building on the side, and he shortened the road. That involved having to trim six plates to produce it. But what it did was it enhanced this sort of vertiginous pull over the edge where you feel like the car isn’t really going to hold onto the road and you’re just going to fall into space.

Which is an actual San Francisco experience, really.

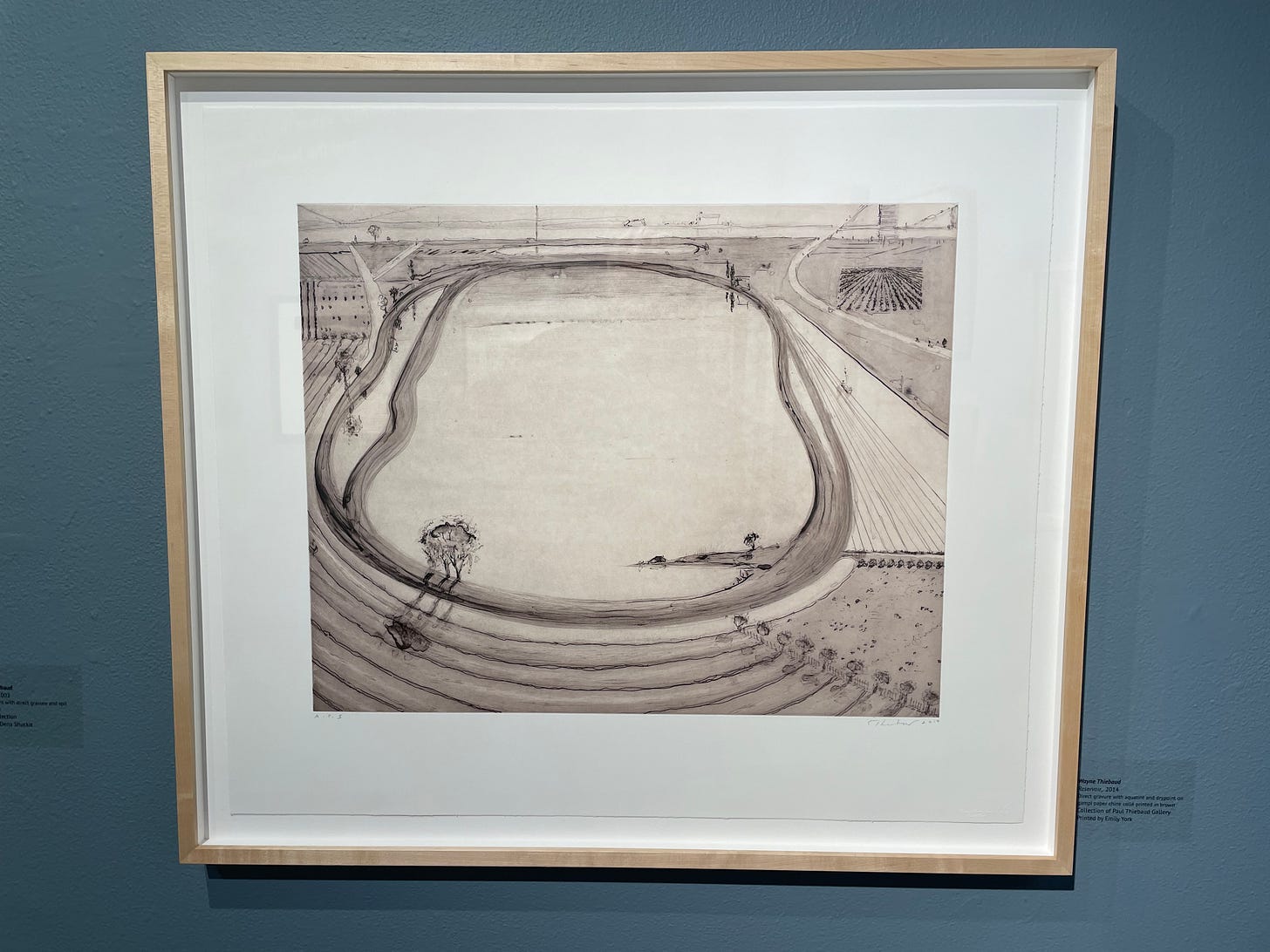

So the other thing that happened later on, at about the time that these were occurring, is he became obsessed with distorting and combining perspectives.

So you look at these pieces at first, and you say, “Oh, I know where I am, and everything looks okay.” And then you realize, “Well, the water seems to be flowing uphill, right? And the shadows are going in five different directions, and like this field here has a completely different perspective,” and it’s very interesting. He became obsessed with that. And there are a whole host of prints and paintings, most of the Delta river paintings that he did, you know, because he lived in Sacramento and taught at UC Davis—most of those involve this distorted perspective.

That concludes our brief tour of The Unknown Thiebaud. The photos here represent just a few of the beautiful prints in this exhibition, so do yourself a favor and head down there.

There will be an opening reception for the exhibition this afternoon, Saturday, Jan. 10, 4 pm to 6 pm. General admission is $15. SebArts members get in free. The Unknown Thiebaud at Sebastopol Center for the Arts runs from January 10 to March 8. The gallery is open Tuesday through Sunday, 10 am to 4 pm.

Don’t miss these Thiebaud-related classes and events at SebArts

Jan 15: SebArts Socials: Tea with Thiebaud. Members are invited to meet-up in the gallery for a social gathering and docent tour. Please RSVP

Thurs, Jan 29: Wayne Thiebaud: The Whole Story

Sat, Jan 31: Printmaking: Copper Plate Drypoint & Monotype Techniques

Sun, Feb 8: Printing with Wayne! A Panel Discussion

Saturday Feb 28, 3-5pm: Film Screening of The Collector, a film about Allan Stone, gallerist to Wayne Thiebaud, with Director Olympia Stone.

Great tour Laura; You convinced me to rush over to the exhibit. This is an amazing display of Thiebaud's work.

"How is it possible that the best exhibitions at Sebastopol Center for the Arts just keep getting better and better?"... so true! And great piece, Laura. Thank you.