Which is better at detecting wildfires: human eyes or AI?

How many wildfire cameras are there in Sonoma County? If you went to the Science Buzz Café on Jan. 12 at Hopmonk, you’d know the answer. Read on...

Samuel Wallis, deputy director of Sonoma County Emergency Management, appeared at Science Buzz Cafe at Hopmonk a couple of weeks ago to talk about wildfire cameras, AI, and other technologies that are used to detect wildfires.

Wallis (who said he was not speaking in an official capacity) introduced his subject: “We’ll talk about fire cameras, which are really cool, and we’re going to talk about the coolest thing, which is the artificial intelligent experiment that Sonoma County did, the first county in the United States that did it, to try and use AI to detect wildfires.” Wallis was good-natured and added some humor to his serious subject.

He said that all those who work on fires “need to know as early as possible where the fire is, whether there’s a fire, and dispatch resources to it as early as possible, so that we can try and contain it before it gets too far.”

The night of the 2017 Tubbs fire was the “worst night of my life,” he said. That night, he was at the County Emergency Operations Center. “Now I will tell you that night, we didn’t have a good handle on where the fire was. We knew there was a fire. It was very obvious, but it was difficult to tell where it was. Communication was breaking down. The people that were out there, the firefighters and the sheriffs and the law enforcement and everybody, they were really focused on life safety. I was trying very desperately to find the fire. I found it at three in the morning when it showed up where I was, like “Oh, there it is.”

After the Tubbs fire, Wallis said CalFire and other organizations realized that what they needed was the capability of quickly figuring out where exactly the fire was. That’s why a network of fire cameras was set up in the county.

Fire Lookout Towers

Wallis said that the original early fire detection system was a set of fire lookout towers, which were placed on the highest peaks in the area. There were about six of them—one was moved from Red Oat Ridge to Pole Mountain in 1981.

“It wasn’t a nine-to-five job. When I was doing research for this, I got a great account of a gentleman at the Pole Mountain fire tower. He would go up there for four or five months at a time, and once a week, a mule with food supplies would be sent up to him and then bring back whatever he wanted to send back. Every once in a while that mule would bring his wife.”

Wallis added that the men were not allowed to have books because reading might take their attention away from their lookout duties. Wallis said that it had to be one of the most boring jobs imaginable in one of the most beautiful places.

Wallis emphasized that one issue was not just spotting a fire but directing fire crews to a precise location. Wallis said that 911 callers reporting fires will often say the fire is “here” or “over there,” which is not helpful.

Fire Camera Network

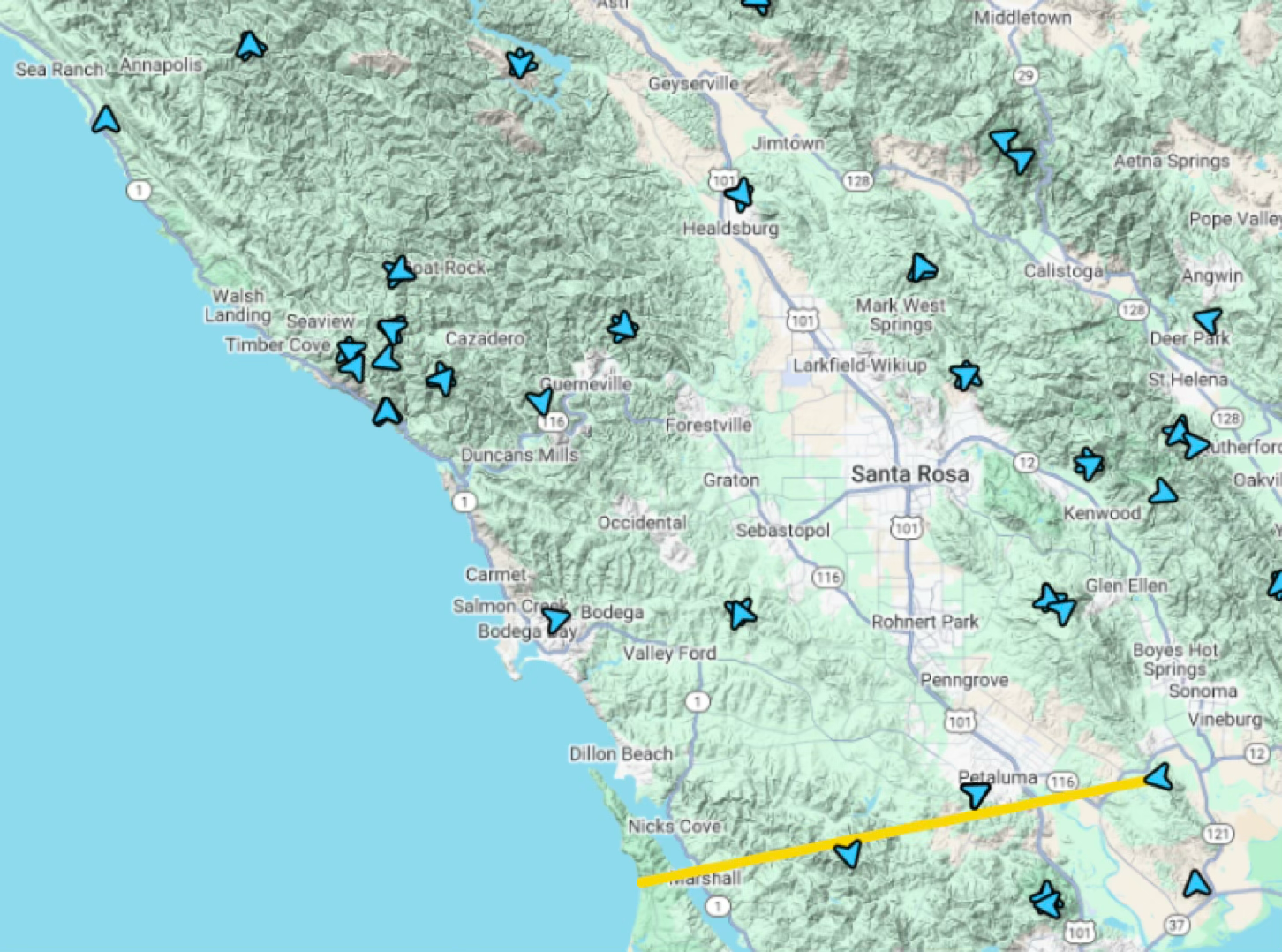

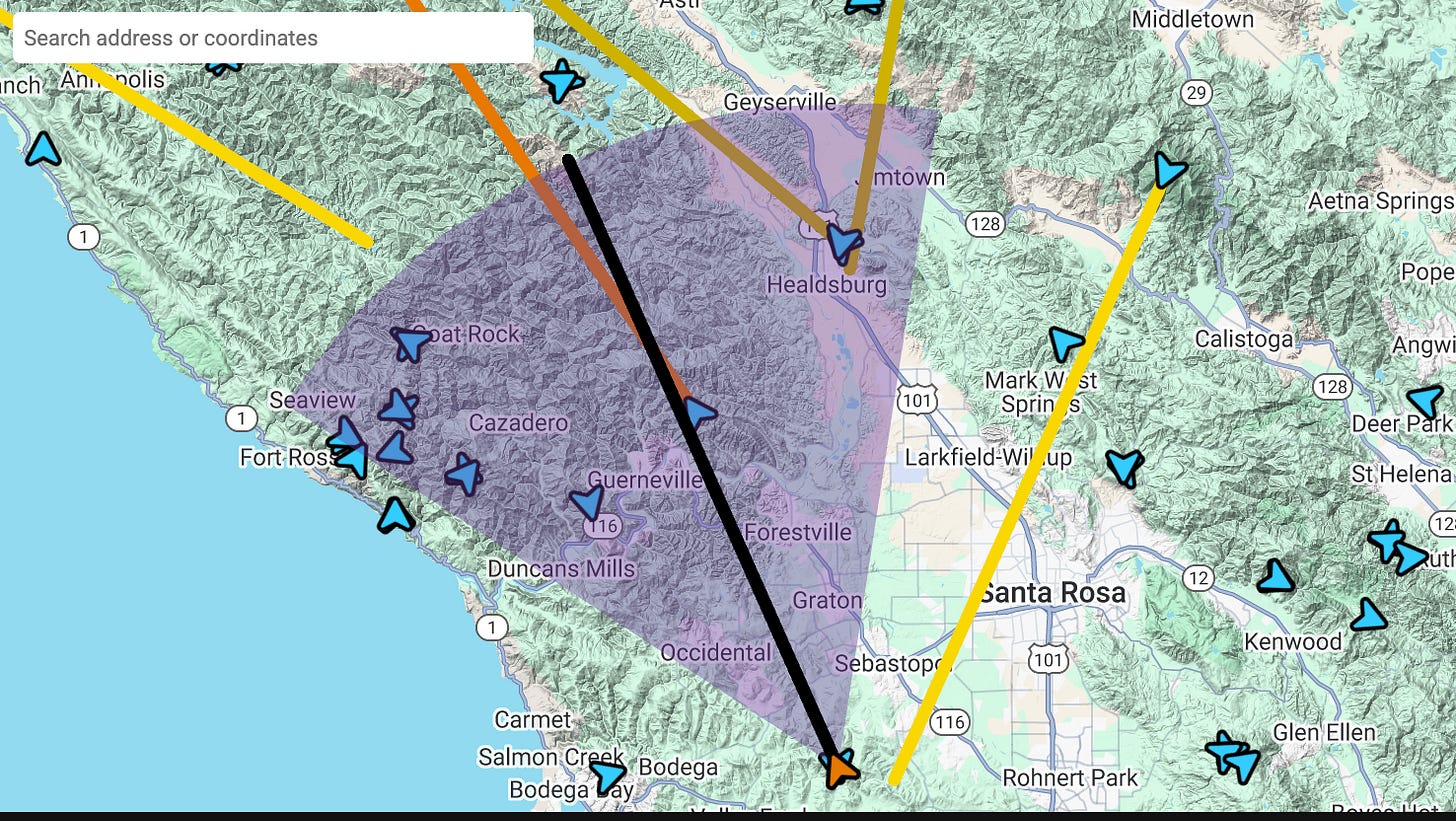

In response to the 2017 fires, Sonoma built a network of fire-detection cameras. “We went from four lookout towers in the county to 40 fire cameras,” he said. There’s your answer—40. They are shown on a map below.

“The first four cameras that we had in the county were actually put there by the Sonoma County Water Agency,” he said. “They specifically installed them around Lake Sonoma. They were afraid that fire would eventually get to the reservoir and contaminate our water supply.”

He said the Fire Detection Network is really about confirmation of a fire, not detection. “When you’re a firefighter, a fire chief, or something like that, you don’t have any visibility,” he said. “You’re just told, ‘We think there’s a fire in this area,’ and then you go out there looking for it. Very often, you can’t see miles and miles, and you don’t really know where the fire is. The fire cameras gave us the capability not only to zero in on where the fire was but also send images to a local fire chief who knew the geography.”

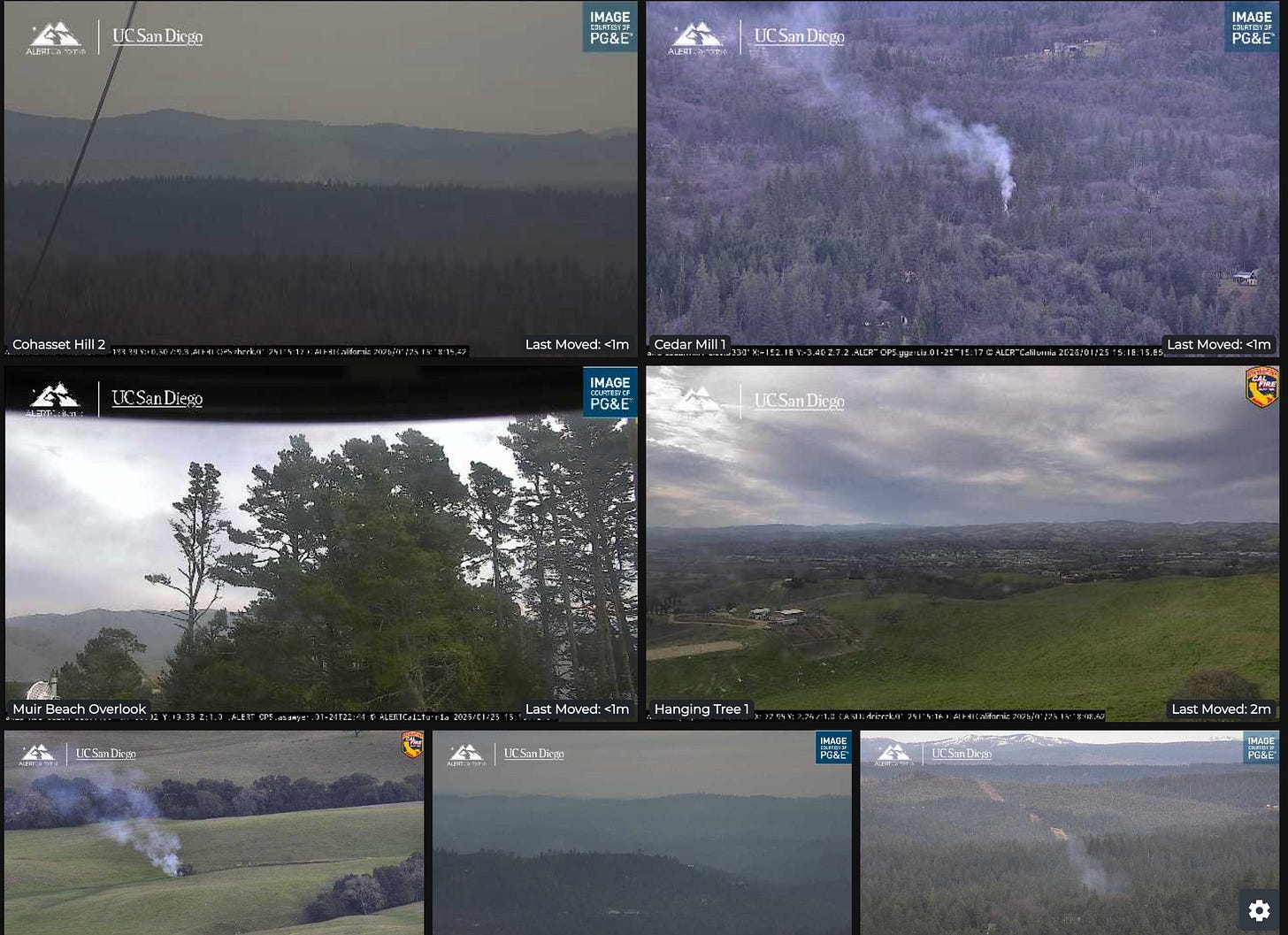

Wallis emphasized that even with 40 cameras, detecting fires depends on where those cameras are pointed and who is watching them. Below is a screenshot from the network website at alertca.live from Sunday afternoon, January 25. You can clearly see that three views show rising smoke.

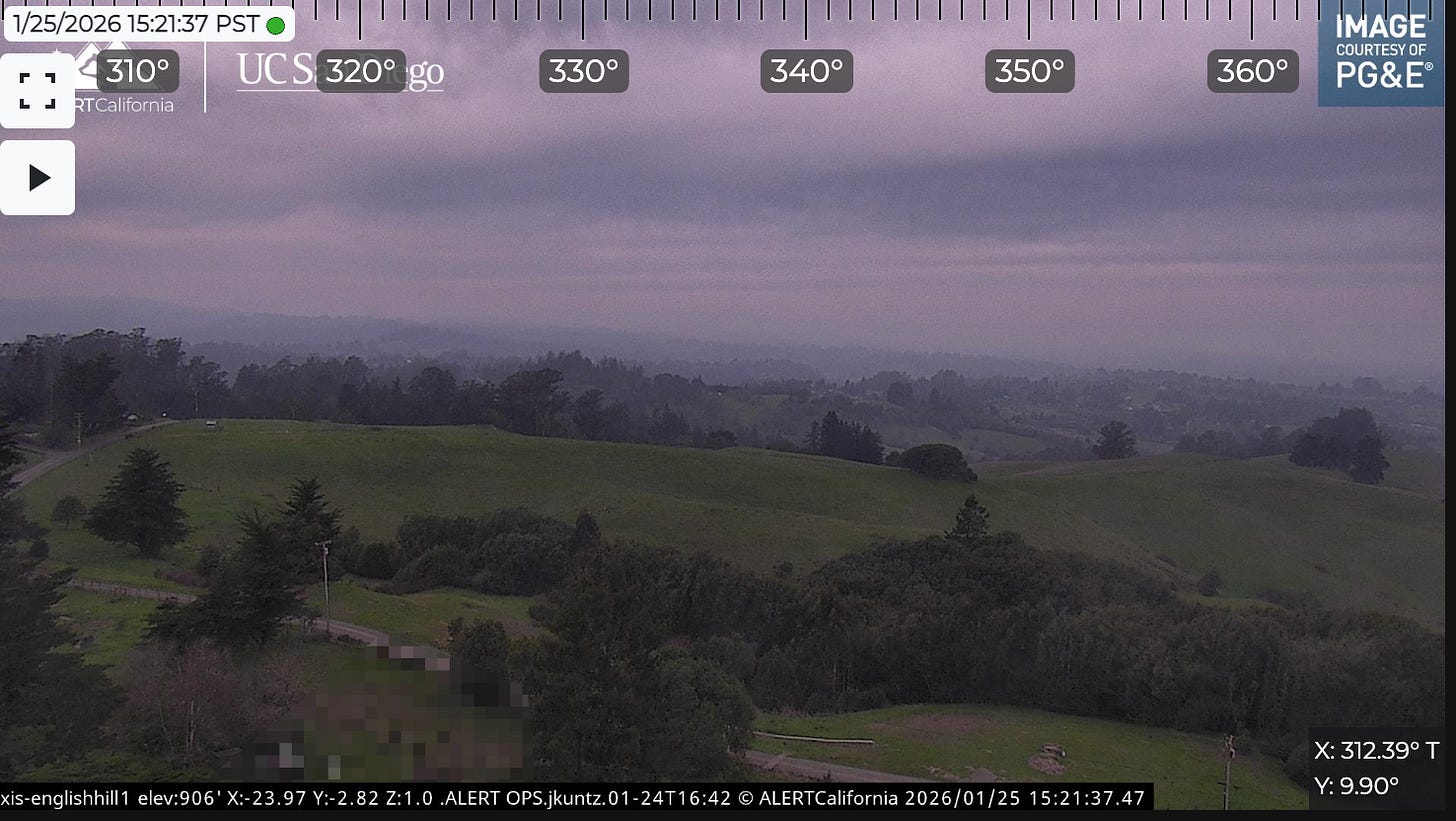

There are a pair of cameras on English Hill near Sebastopol, and you can access them yourself at alertca.live. Here is a screenshot from the camera on a foggy Sunday afternoon.

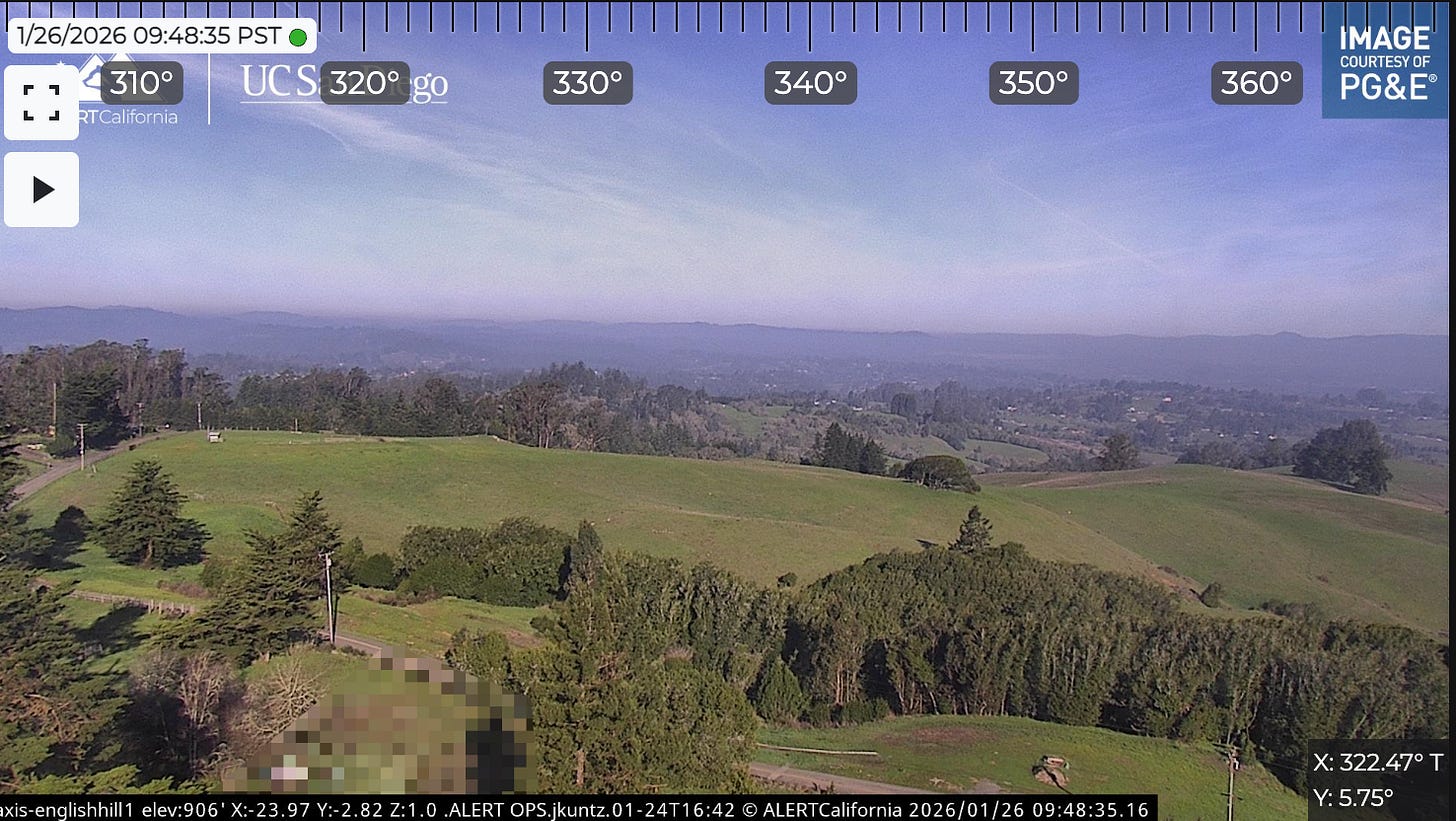

The next morning, the skies were clear and visibility was much improved.

Here is the map view of the English Hill camera, showing that it points northwest towards Sebastopol. The cameras can be moved automatically in different directions but only by State-authorized users.

AI as sentinel

One problem with having 40 cameras is that the government doesn’t have staff to watch all of the cameras 24/7, Wallis said. A woman in the audience raised her hand and asked if they had ever considered using AI to monitor the cameras. It was a perfect segue to the most interesting part of his presentation. Starting in March 2021, Sonoma became the first county in the country to experiment with artificial intelligence to detect wildfires early on.

“We asked for and got a $300,000 grant from the federal government,” said Wallis.

”Sounds like a lot of money, right?” They submitted the grant in 2018, and it was 2020 before they started work on a two-year pilot program.

The AI system went operational in March 2021. If a fire was detected, alerts would be sent to local fire chief. Wallis said, “We started it up and then we shut it down as soon as we could. The AI was like a golden retriever on Adderall; it went crazy. Because this is March, with all those vineyards, they’re burning off all the debris, and the fire cameras are going: ‘I found one, I found one. I got one.’ All of those alerts are going to almost all my fire chiefs and ringing their phone saying there’s a fire in your area. We had to shut it down quick.” They decided to hold off on testing until later when burn permits were no longer being issued. “It was a lot more calm after that,” he said. “After that, if we got a ding, there was a decent chance there was an actual fire.”

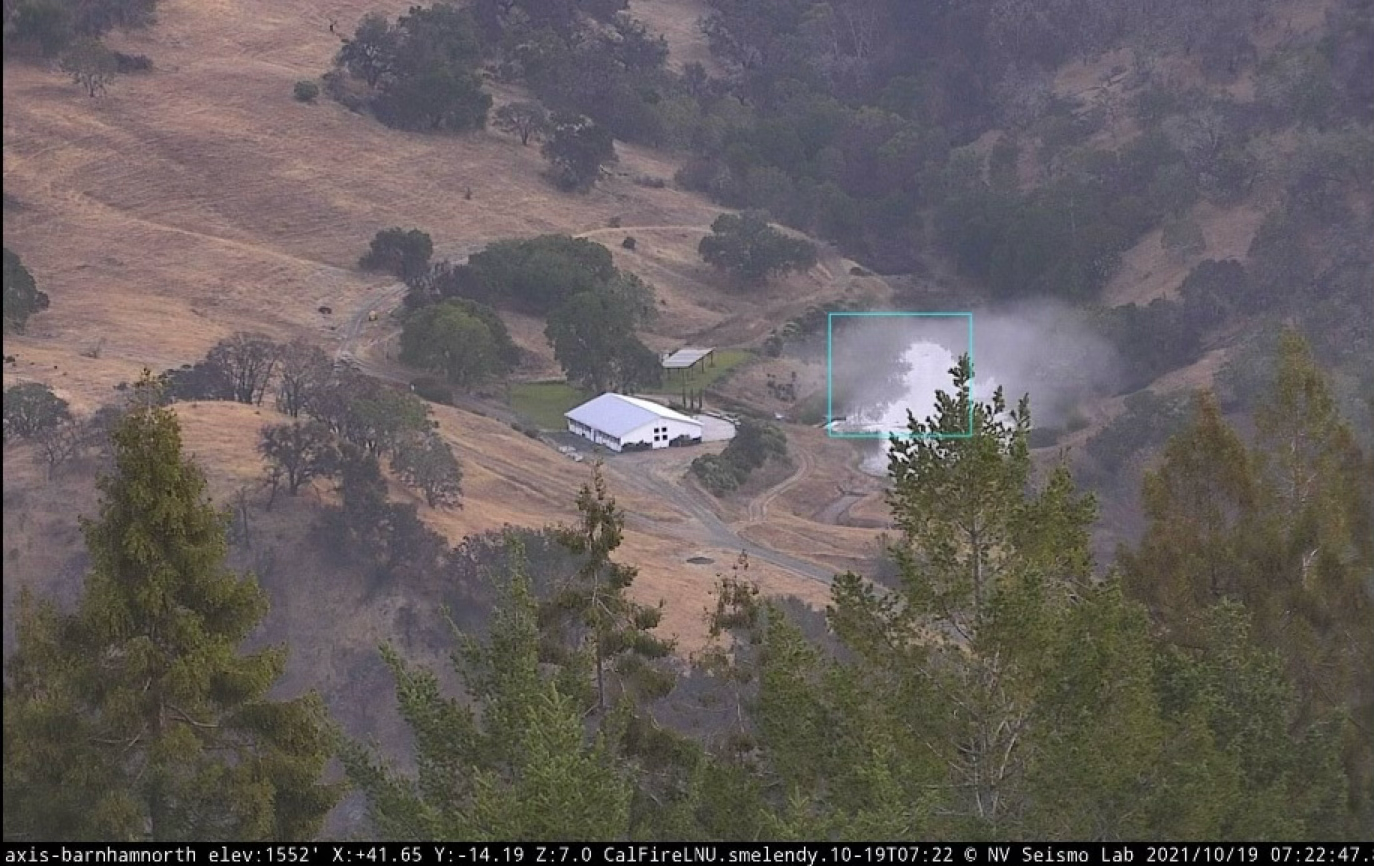

Every 10 seconds, each fire camera is taking a picture. “If the fire camera is taking pictures of the Mayacamas Mountains, it’s taking six-a-minute. That’s 360 an hour, and what it’s going to do is compare each new picture to all the other pictures that it’s taken of the Mayacamas Mountains. That’s a lot of pictures, millions of them. The AI is going through and looking at the picture it just took and comparing it to all the pictures that it took before that, to see if there’s anything different—specifically, if there’s anything that looks like smoke.”

Wallis explained that AI produced true positives and false positives. Sometimes, when it detected a wildfire, it was a wildfire; other times, it detected a wildfire, but something else was happening that fooled it. A vineyard burning old vines creates smoke but is not a wildfire. Fog on a lake looks like smoke, especially as it dissipates.

In parallel to the AI system, there’s a dispatcher receives the 911 calls and sends an alert to a local fire department. “The important thing is the dispatcher has the responsibility to look at the fire, swivel the cameras over, take a look at the data, and make a decision of what’s going to happen, and then order that we send a fire engine,” said Wallis.

The cameras are constantly taking pictures and sending them to a remote server, where the AI analyzes them. If it detects a fire, an alert is sent to the dispatcher.

Guess what was faster at alerting the dispatcher to the presence of a new fire: humans calling 911 or the AI system?

Wallis said that “911 calls alerted the dispatcher to the fire before the AI system did in about 90-95% of the time.”

“The 911 caller beat the AI,” he said. “Humans are better than computers, and there’s a lot of reasons for this. We spent a lot of time scratching our heads, figuring what the heck happens here. The number one reason we came up with is that humans start fires. Ninety-nine percent of possible fires were started by humans, and most humans, when they start a fire, they call 911. If Farmer Brown is on his tractor and he sets everything on fire, he calls 911 because he doesn’t want his farm to burn down. So they have an incentive to call, which means they’re usually calling even before the AI has an opportunity to detect the wildfire.”

While 911 callers generally are faster at detecting fires, Wallis cautioned that “some of those 911 callers can be wrong as well.”

After the funding ran out in 2023, the use of AI for fire detection in Sonoma County ended. Wallis said that the state of California picked up an AI system to try and detect wildfires. “We told them what our experiences were. They said, ‘Thank you very much. We’re going to try it anyway.’”

The next big thing is using satellites

The next big thing for detecting fires is using satellite imagery. “One of the challenges is that we can’t get a camera looking down into a canyon,” he said. “If we can’t see down there, then we’re not going to see anything.”

Satellites have changed dramatically in just the last five or 10 years, with resolution down to 5x5 meters. But the process of getting image data is slow, and soon there will be millions more images. The upside is that the more detailed imagery, if accessible, would help in confirmation of a fire and honing in on its location.

“Ultimately, the best fire detector remains a human with a cell phone,” he concluded.

Kudos to Daniel Osmer for organizing another stimulating program at Science Buzz Cafe. Click here and scroll to the bottom of the page to sign up for Science Buzz updates.

Having been at Science Buzz along with Dale, Jennifer, Daniel D and Blake to hear Sam's talk, I can say this is excellent report on the important details Sam wanted us to know! And going the extra mile to show the web visuals of the cameras helps to show their value even more. Ditto on kudos to Daniel O & Science Buzz Cafe and for Seb Times reporting!!