On Memorial Day for every year that Alan Murakami can remember, his family went down to the National Golden Gate Cemetery in San Bruno to lay flowers beside the grave of Peter Masuoka, his uncle. During Covid, Alan decided he had the time to write about his uncle and his Japanese-American family. Peter, who grew up in Sebastopol, died in France fighting for his country in the 442nd Battalion in World War II, all the while his family was held in an internment camp in Colorado.

Alan’s grandfather was a first-generation Japanese-American, known as Issei. Alan’s mother and her brothers, including Peter, were second generation, known as Nisei. As a member of the third generation, Alan had filled a shoe box with scraps of paper where he had jotted down what members of his family had said about Peter. He started with the shoebox and began trying to piece together the life of the uncle he never knew. Peter Matsuoka’s story and the Matsuoka-Murakami’s family story are an important part of the history of Sonoma County, which some of us might not know so well.

To order a copy of Alan’s book, you can contact him at amurakami6@yahoo.com.

Transcript

Dale: Today I am joined by author Alan K. Murakami, who has written a book subtitled, "The Uncle I Never Knew." It's a memoir, almost a family memoir. It's titled, Peter Masuoka, which is the name of his uncle. First of all, welcome. Nice to have you here.

Alan: Thank you. Thank you.

Dale: Give me a little bit about yourself.

Alan: I grew up in West Sonoma County. And I'm the third generation of Masuoka - Murakami. I went to the local schools here, El Molino which my parents and Pete, they went to Analy as well as my sons. So I guess I was the black sheep. After going to school and UC Davis, I came back to Sonoma County to be near my folks. So I've been lucky to both grew up in this area, work in this area, and to be able to write a book in this area.

Dale: How did your family come to locate itself in this area, in the outskirts of Sebastopol?

Alan: Let's see. My grandfather, Pete's dad, Harry Masuoka, came over from Japan. He was born in Okayama, and he came over in, I think, 1906, to San Francisco. So he experienced the great earthquake then so that was kinda a welcome thing for him. He heard good things about the agricultural possibilities here in Sonoma County and he predominantly lived in Sebastopol.

Dale: It's not unlike Italian immigrants coming to Sonoma County. They were Japanese immigrants and, but they end up really starting with an apple orchard, right?

Alan: Yes. Starting growing apples and at that time it was really big to pick the apples and dry them. There were some very famous apple dryers, I believe, the Barlow that we have downtown. That was a family that did a lot of apple drying. My folks, they used to go pick apples and help dry 'em, pack 'em. It was quite a big industry.

Dale: Why did you decide to write this book about your uncle?

Alan: When Covid hit, I found myself during the shelter-in-place thinking, I got some time on my hands. Why don't I pull out this old shoebox that I had stuck notes from family get-togethers like reunions and weddings, and when people would talk about Pete, I would jot it down on a napkin or the program and I just saved them. I guess I felt like I was a family historian to some degree. I said I know about my other uncles because I met them, but I don't know a great deal about Pete.

I've heard stories, right? But I really wanted to get to know the individual. So I sat down and started to write; this was about three years ago. It's been a profound journey doing this, full of these encounters that have really touched my soul. In general, the story kind of told itself which was very, very comforting and very rewarding. .

Dale: To get into that story a little bit, Peter has what I might consider an ordinary life growing up here in Sebastopol.

Alan: It was hard writing this because there wasn't a lot of information about Pete. And so I really had to try to gather information from those that are still around that I could talk to, like my mom, his sister.

I knew that he was born in Sonoma and this was back in the 1920s. He went to the local schools and the family lived just off of Hurlbut, so it was close to Analy. I can imagine him walking to school. I learned that he was a very good athlete as well as he was successful at academics.

He was the first Japanese American to receive the American Legion Award as a senior. That was quite an honor. The athletics was interesting because I was able to learn from my mom and also my Aunt Ginger Masouka, Pete was a left-handed individual. At the time in public education, everyone was taught to write right-handed. So that's why my mom says that's why Pete's handwriting is so illegible.

I think he was a very humble person. I don't think if he was around today, he would talk about his achievements. He went to the JC and played football and tried rugby there.

One of those profound moments was when I was helping my mom declutter one of her backrooms. I saw in the back these two old scrapbooks and this person by the name of Jack Acorn had made them. They were full of the SRJC, the junior college football team records and pictures of the players. There was a picture of Pete. I go mom, how'd you get this? She goes, I don't know. I learned that he continued to play on the grid iron there, and did fairly well. As a side, I looked up Jack Acorn on the internet thinking, gee, it'd be great to get these back to the Acorn family. And I was able to. I was able to get in touch with his son Michael, and he lived in Petaluma as had his Dad. We had a nice chat and with his permission I donated those books, the scrapbooks to the Junior College Historical Society,

Dale: That's great. Now, your family was also members of the Emmanji Temple in Sebastopol.

Alan: Yeah. Yeah. There were ties to Buddhist church there. Though a lot of the Japanese Americans were Buddhist, our family gravitated more to Christianity. In fact, in the camp, internment camp, that's where my mom really became convinced that Christianity was her calling. I don't know what Pete would say.

Dale: I was fascinated by the temple, that its origins were at from a World's Fair in San Francisco.

Alan: The local community people, they heard about this building and they basically made a plea, can we please buy this and have it shipped out to Sebastopol? And then it was resurrected.

Dale: You mentioned it already, World War II happens, and this is part of where, the ordinary life that Peter had becomes extraordinary. Your whole family is deeply affected by this.

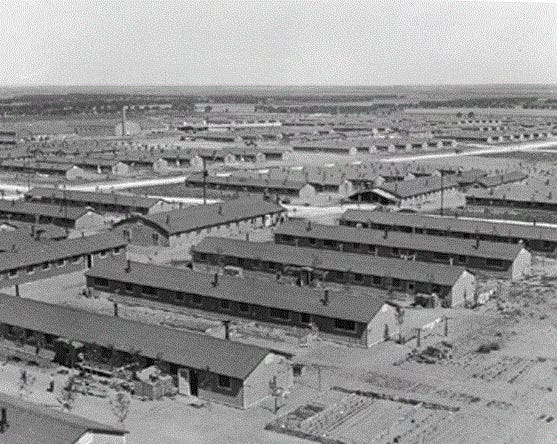

Alan: My parents, the Masuokas, they lived in Sebastopol and right after the attack at Pearl Harbor, the President of the United States signed an Executive Order to have all Japanese Americans on the West Coast to be basically rounded up and put into internment camps. Some people call them prison camps. Some people call them concentration camps. I like to make a distinction that these concentration camps were very different to what happened in Germany and the concentration camps there.

That said, my parents were told you have to move. You have to go. And what's amazing about is how fast this happened. Many Japanese Americans were given maybe a week, maybe two, to sell everything, to close their businesses. They didn't know where to go, that's just amazing.

So they basically could take only what they could carry, like a small suitcase. I asked myself, what do you pack? You don't know where you're going, so you don't know if you're gonna bring clothes for snow. The desert. So do you bring your books? You just basically bring your bare essentials?

The folks here in Sonoma County, they were told in order to attend to the Santa Rosa Railroad station, the depot there. So they got there. A funny little story is that mom's good friend Barbara Bertoli, and they're still close, Barbara's mom, I think she worked or was associated with some sort of a Red Cross agency. My mom always remembered this. When the Masuokas got to the train station, she saw Barbara's mom and she had sandwiches for people.

Many places in the West Coast, emotions were very high, right? And in many places where the Japanese lived, there was a lot of resentment; there was a lot of hatred, anger; there was violence.

Here in Sonoma County, in general, the people treated the Japanese Americans, I think with really a kind heart. For example, they would help some of the Japanese Americans take care of their things while they were gone, pay their property taxes so they wouldn't lose their property. So, it really speaks well to the folks here in Sonoma County..

Dale: You described this, but first generation and second generation Japanese. Was it your grandparents were first generation, Issei and Nisei are second generation. Is that right?

Alan: That's right.

Dale: The point of that is you are American citizens. It really is sad that they did not recognize your status as citizens and your rights as citizens.

Alan: Exactly. True. In fact my dad, Jim Murakami, in the book, I talked a little bit about some of his pretty traumatic experiences he had when he was going to Analy and about racial injustices.

After the war, he became an advocate for civil rights, specifically the Japanese-American Civil Rights. He first became a president of the local Japanese-American Citizens League. Then he climbed the ranks, culminating in being president of the National Japanese American Citizens League. He was a very humble person. He probably would give me the eye if he was here and heard me talking about him. I'm proud to say that he, along with many others, were instrumental in getting reparations and redress passed through the US Congress for Japanese Americans who were unjustly put into camps.

Dale: How long was that period?

Alan: Yeah, they were in camp in 1942. And again, they didn't know where they were gonna go. They first went to assembly centers.

The Sonoma County bunch were directed to the Merced Assembly Center where they stayed for a couple of months, I wanna say, because the US Army and the US government, they said, okay, you folks have to move. But they didn't have really a great plan on what to do, so they were still building the camps. So after the camps were basically almost completed, then they were shipped by train from Merced to Colorado (to the Amache Japanese Internment Camp.)

Dale: You mentioned in the book, the different weather each time they moved. It was warmer in Merced than it was Sonoma County. Then it was colder in Colorado than it was in Sonoma County.

Alan: That's so true. I have a great picture in the book. It's one of my favorite ones of my mom and her parents in Colorado. It was like a photo op because they weren't allowed to have cameras in camp, so I'm not sure how those (photos) came to be. But different families stood in front of this huge snowman. It must be about 12-14 feet tall. My mom's dressed in a dress, and it just signifies that's all she packed was this dress to be in the Colorado snow.

Later after things got settled down in camp, they had rhythms. They were finally able to order clothing from like Montgomery Wards, I think it was, or Sears, and they finally were able to get boots and Woolies and that sort of thing.

Dale: Peter. is at the JC , as we were last talking about him here. He goes with the family to the internment camp, is that correct?

Alan: Yes, he does.

Dale: But then he enlists in the army, is that right?

Alan: Yes. He enlists in the army when in camp, which I can't imagine. Here you are in this place, you're told by your government with the connotation that you're disloyal: we don't trust you. Then the Army, knowing they need more young men to fight in Europe and Japan, comes to you and says, will you join us? So Pete did.

I asked my mom this. I said were there any misgivings that Pete had? She said, no, unequivocally, no. She said her father, Harry, and all of the brothers wanted to prove they were loyal Americans. And so Pete enlisted.

Dale: That was about 1943.

Alan: Yes.

Dale: What happens to him from that point on?

Alan: He enters the army and he goes to Camp Shelby in Mississippi where he does his basic training. He's there for maybe a little over a year. Here's where I don't have a lot of records. What I've been able to ascertain is he was trained to be in headquarters company, which was doing things like clerical, but also they had some artillery training.

Pete was ultimately assigned to his artillery unit. While there (at Camp Shelby), he had opportunities to go visit other places on when he was on leave. He actually was able to come back to Amache. He had one leave to go there. I don't mention this in the book. I have a picture of him in camp with his uniform and he's turned away. But he is smiling and he is holding a flag and his mom's in the picture. What my mom tells me is that this was a propaganda photo taken by Paramount showing that the camp was wonderful, that everyone was happy. So that was a little aside. Then, after basic, he was assigned to the very famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was a segregated unit, except for the officers who were Caucasians. So he was with that very famous unit, which was the most highly decorated unit ever in military history for its size. They had that many casualties and awards and such. He and his brother were both in the 442. Eventually Pete shipped out to go to Italy. That's where the 442 met up with the 100th battalion, which was from Hawaii. Pete fought in the campaigns in Italy first, and saw battle there. After that, then they were ordered to go into France.

Dale: Occupied France, right?

Alan: Yeah. I can't even imagine because many of the Nisei did not talk about the horrors of war, what they experienced. But it was very horrific. I just can't even imagine what they went through. When Pete was over in France, there were these huge battles that they were fighting with the Germans and the Germans had been there for over a couple years, so they were entrenched. They knew where to be in order to inflict the most casualties.

The US Army had many tough battles to move toward Germany. Hitler was very adamant: you folks have to stop these armies or if they cross this one mountain range (Vosges), then we will lose the war. So they were very motivated to stop the Army advances. As the days went by, the 442 was making progress along with the 100th.

Then there was this one battle that is very important and it was called the Rescue of the Lost Battalion. There was this one US group that was cut off from friendly lines and they were surrounded by the Germans and the US Army sent different rescue groups over and over again. They couldn't get through. The Texans were just being cut off and it did not look good. So finally they ordered the 442. We got to send these guys in; they seem to be able to get it done. I'm not saying that the other units didn't, but 442 had had successes and so they advanced over and over again and finally they were able to rescue this lost battalion.

As a side note, I mentioned, the Barlow family. Tom Barlow went to Analy and this is in the book. I'm not sure how Tom got assigned to this Texas Battalion but he was one of those that was in that group that was rescued. I can only wonder, I wish I could ask Pete, did you see Tom. What a moment, right?

The 442 experienced so many casualties during that mission. This was in November 1944. Pete survived that horrific battle. Then this one day, he was assigned to a mission but he did that mission in the morning, came back and he was tired. All these guys were just exhausted. One of the leaders said, okay, we need another group to go out and get some of the wounded. Lens Murakami was supposed to go and he said, I don't feel well, and I might make note his last name is Murakami. No relation.

Being the volunteer that he is or was, Peter says: I'll go. I have a picture of that day where he is standing next to a Jeep with Lens Murakami, this other individual, and on the back of it says November 3rd. I'll get back to that important piece. Pete raises his hand, volunteers, and goes out to rescue these soldiers.

As he's doing that, a mortar round comes down and Pete orders his men to go to the left and he dives to the right. He's killed by this mortar round. So, on the back of that photograph, I asked my mom, was this taken the day that Pete died? It was.

So after he was killed, his buddies back at the camp were told. They went out and said we're not leaving Pete behind. We're gonna go and get his body. They took a vehicle and got Pete and brought him back

Dale: He was originally buried in France.

Alan: Yes, he was. In Épinal, France was where he was first laid. After the war, the US Army asked his mom, would you like him to stay there? Or we can bring Pete home. She elected to have him come back to California. He's currently at the National Golden Gate Cemetery in San Bruno. Every Memorial Day we go and see Pete, and we take flowers.

Dale: That's how your book opens. It was a annual ritual for your family to go down there on Memorial Day, wasn't it?

Alan: Yes, we do. We've been doing it since I can remember. .

Dale: So you grew up wondering who he was?

Alan: Yes, I always heard bits and pieces, but I didn't know who was this individual. I ascertained that he was a quiet individual, modest. Out of all of the Masuoka boys, he was the only one in Boy Scouts. That was a revelation to me. He liked to go on dates and and he was engaged. What was another very profound experience when writing this and being on this journey of writing was I learned about his fiance and her name was Holly. This person named Marsha Onamia Evans contacted me out of the blue and said, hi, I'm Holly's niece. She said, “Holly passed (around March of 2022) and I have some possessions that I think you, the Masuokas would like to have.”

So we met and Marsha hands over this trinket. It's this little gold locket and when you open it, it has a picture of Pete and a picture of Holly inside. It was so amazing because even though they were engaged to be married in camp they decided to break off the engagement.

I tried to ascertain why was that? I learned from my mom that Pete had asked his dad, Harry: I'm thinking of marrying Holly. My grandpa says to Pete: “you might wanna consider that because you know you're going off to war, and if something happens, she's going to be a widow.” So he says: “you're right. I think maybe we should wait.”

I asked Marsha what was Holly's thinking? And Marsha shared with me that Holly was a very private person. Very quiet. Didn't say a lot. But what she gathered was that Holly thought: I'm really the person that's taking care of my parents, (her parents) and so I don't think I can commit to married life right now.

After they broke it off and Pete died, Holly never married. That signifies that she loved Pete so much and so she never committed to another relationship. She still kept those mementos too.

Dale: Did they meet at the camp?

Alan: Good question. They met at, I think, he was in Analy and she was going to another high school. So they met before Pearl Harbor. So they had a relationship and dated and then they were both in camp, both families were at Amache.

Dale: Were people in camp until the end of the war?

Alan: Yes. They were there until the end of the war and then after the war the Japanese and Chinese Americans were told, okay you can go home. They go, okay. I think they were given like $20-25 each or something like that.

So you go, okay, I'm here for year or two, and I go home. What does that look like? Some people didn't have homes to go to because they lost them. Again, here in Sonoma County many were able to return and they had their farms and businesses to return to. They had to start over to some degree. Interesting aside is my grandfather Harry had some close connections to many of the Caucasian families here in Sebastopol. He was invited to come before a lot of the folks, and he ran a hostel, and when the families came back over, he would well help those families to have a place to stay while they got their things in order.

Feelings again were running pretty high even after the war. One family, the Muritas, when they came back, a couple days after, someone fired gunshots toward their house. Mr. Murita contacted my grandfather to ask, what do I do?

Harry said, go to the Chief of Police in Sebastopol. They didn't have a car yet, so they had to walk into town and the chief was very helpful and supportive. So it wasn't an easy go, but I think it was easier than other communities in California.

Dale: Alan, would you read a segment from your book?

Alan: Sure. It was hard for me to choose what to read. So I just thought about chapter five, where he's spending time at Analy and at the junior college. So here's a piece.

My Aunt Ginger shared that when she was beginning to date her future husband, Pete's brother, Frank, that Frank once said something to her that was mesmerizing and profound. He said, with a tear in his eye, no one can come up to be an equal to Pete Masuoka. He's the greatest football player I've ever seen.

Margaret added that h e was a good athlete and a pretty not bad quarterback. And during those games at Analy, the high school radio announcer would sometime describe Pete's great plays by saying, "and that Pete Mazooka threw a great pass." The next day, mom at Analy would get teased at school and friends would smile and say, Margie, who is this, Pete Mazooka?

Dale: Good. Thank you, Alan, for telling us about Peter Masuoka.

Alan: You're welcome, Dale. Thank you.

To order a copy of this book, contact Alan at amurakami6@yahoo.com.