Mobile Support Team to the rescue

When a housemate ran into trouble, the county's Mobile Support Team was there to help

It’s hard to know just when my housemate’s behavior crossed the line from “She just needs a little time to recover” to “We need some serious help here now.”

But one day, the following thing happened simultaneously: without saying a word, her boyfriend walked out onto the back porch to make a telephone call. I walked outside onto our driveway to do the same. Unbeknownst to each other, we were calling the same place: Sonoma County’s Mobile Support Team, a service that provides onsite help for people having a serious mental health crisis.

After I hung up, I walked back into the kitchen, casually gathered up all the knives, wrapped them in a dishtowel, and hid them in a drawer in our bedroom.

An hour later, a little car bearing the logo of the Mobile Support Team rolled down our driveway, and two sympathetic-looking people—a man and a woman—climbed out and asked why we’d called them.

I explained briefly what had happened: A few weeks before our housemate—a sweet, smart, lovely 20-something—contracted poison oak. When it went systemic—she was covered with it head to toe—I took her to a local doctor who prescribed prednisone. I don’t recall how long she took the medication, but within a week, her personality began to change. She transformed from a calm, focused, organized person into someone who was teary, distracted, and oddly on edge. At first, I thought it was just the itching. Her boyfriend was visiting from another state, and his presence seemed to calm her, but slowly, as the days passed, she began to lose touch with reality: she thought our other housemate was poisoning her, and one morning, she didn’t recognize me when I walked into the kitchen. She thought I was just some random stranger walking into the house.

After I shared this story, the folks from the Mobile Support Team went to talk with our housemate, who was sitting on the grass with her boyfriend in our backyard. The team sat down next to her and chatted quietly with her. After a while, they convinced her to come with them to the hospital, where she could be evaluated by a doctor.

I remembered that day recently when Behavioral Health Division Director Dr. Jan Cobaleda-Kegler and Wendy Tappon, the client care manager for the Mobile Support Team, gave a presentation to the Sebastopol City Council.

The council is looking for ways to provide extra support for the Sebastopol Police Department, which is seeing an increasing number of behavioral health-related calls. The city is hoping that the Mobile Support Team (MST) can take some of those calls off their hands.

What is the Mobile Support Team?

Sonoma County Mobile Response was founded in 2012. It expanded into West County in 2019. For much of its history, until 2024, it was only accessible via a call to the police. If the call seemed to require a behavioral health specialist, the police would call the Mobile Response Team to meet them at the scene. That all changed in 2024.

The California Department of Health Care Services, which is responsible for administering the Medi-Cal program, notified all counties in California that by 2024, they would be required to implement the Medi-Cal Mobile Crisis Services Benefit, providing 24/7 mobile crisis services to individuals experiencing behavioral health crises.

The good news was that this would enable Sonoma County Department of Health Services (DHS) to access funding through the Medi-Cal program.

As a part of this change, the county was required to do the following:

Set up a single crisis service hotline that runs 24/7, 365 days a year, and can dispatch a team anywhere in the county. (That number is 1-800-746-8181)

Have a standardized dispatch tool and procedures to triage crisis, determine dispatch needs, level of intervention.

The service must be provided at an individual’s location, anywhere in the county.

Mobile support teams must consist of two providers with access to a licensed mental health professional. One must be trained to conduct crisis assessment. One must carry and be trained to administer Naloxone. Tappon said that on both their daytime shifts, one of the team members is a licensed clinician.

To meet these requirements, the County expanded its existing Mobile Support Team program.

“So we got this mandate, and in April of 2024, on April 16, we did our soft launch,” Tappon said. “We were able to go full 24/7 on June 2, 2024. We launched our 24-hour call center at that time, along with our full response and getting our teams up and running. We did it very quickly in about six months.”

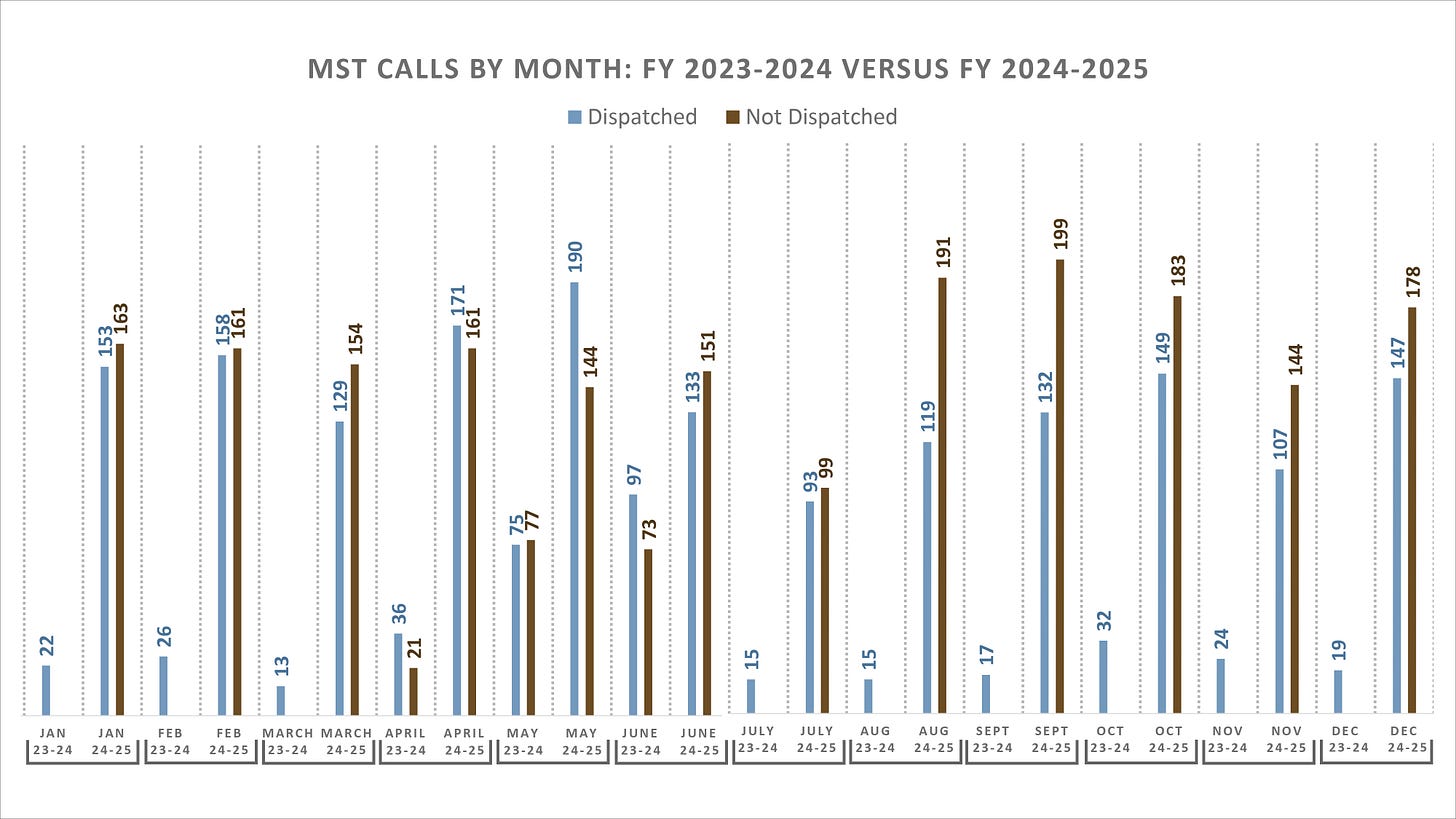

Tappon said it was an immediate success. The number of calls per month leapt from the low teens and twenties into the hundreds. “Before we were severely underutilized,” she said.

“Now we can take the call, get the information that we need, go out to where that person is, help them with their crisis, do what we can to hopefully stabilize them in their environment, because that’s the most trauma-informed way to help support that person,” Tappon said. “If we’re not able to do so, if that’s not the safest thing for that person, we can offer a 51-50, get them to a higher level of care, transport them in our vehicles to either CSU [Crisis Stabilization Unit] or to a hospital, and hopefully not include law enforcement if we don’t need to do so.”

“On 70% of our calls, we’re responding without law enforcement, and 30% of our calls are still responses with law enforcement,” Tappon said.

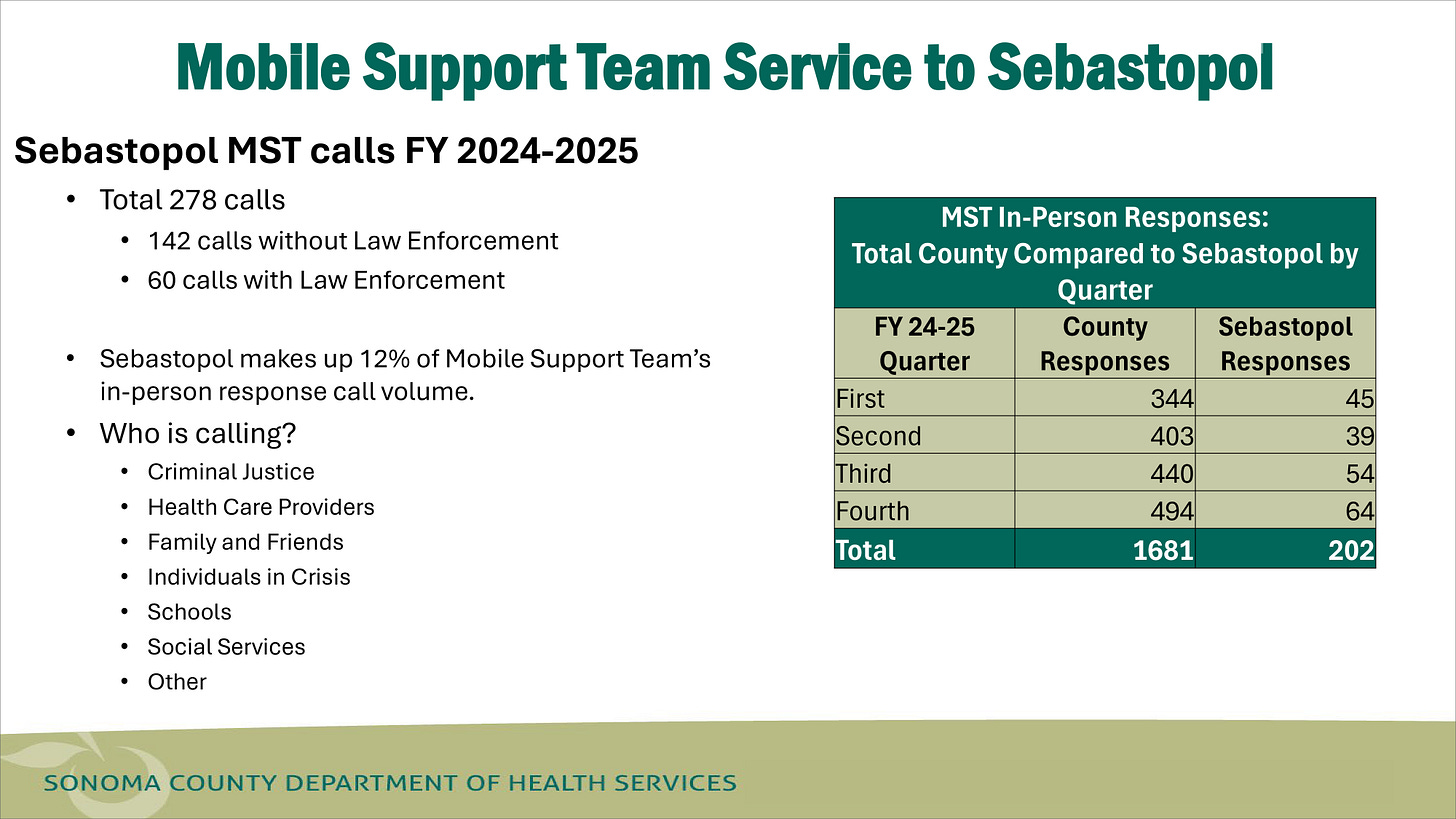

Here’s the data for Sebastopol in 2024-2025: there were a total of 278 calls — 142 involved the police and 60 didn’t.

During council questioning, DHS Director Nolan Sullivan explained what kind of issues Mobile Crisis Support could help with and what it couldn’t.

“I hear you need help here in Sebastopol,” Sullivan said, noting that this was his third meeting in Sebastopol in as many months. “I understand that your police department has challenges with the number of calls, and they want to focus on law enforcement calls. The county is going to do our absolute best to assist—where we have homeless resources for outreach and assist for crises, but there’s still going to be a gap, right?”

He said there was a big difference between a nuisance issue, a mobile crisis issue, and a law enforcement issue. “Mobile Crisis is not going to solve your nuisance issues. You may have someone that’s slightly inebriated, maybe they’ve got some benign mental health issues. They’re bugging people. They’re bothering people. It’s not a crisis, though. So I want to set expectations: Mobile Crisis will not solve hundreds of your police calls.”

He also reminded the council that they weren’t the only municipality needing help. “The county has almost half a million people,” he said. “You’ve got about 10,000 in Sebastopol,” he said. “We’re going to do our best to provide some help and resources here. We’re here, we’re at the table, we’re willing, but we’re getting these calls from Guerneville and from all of our partners wanting more.”

What happens during a Mobile Crisis visit?

Tappon mentioned that it’s possible to get from the MST office to Sebastopol in less than 15 minutes. This is assuming the team is not on another call, in which case, of course, it will take longer. When you speak with MST dispatch on the phone, they’ll estimate how long it will take to make it to your house or business. I live in Forestville, and, at the time we called, the dispatcher estimated it would take about an hour to an hour-and-a-half to reach us. Clearly, in an emergency situation, it would be faster to call the police. But in our case, that wasn’t necessary.

Mobile Support Services has 32 staff members: 12 clinicians/clinician interns (two of which are supervisors), seven alcohol and drug counselors, 10 client support specialists, and three admin staff. In terms of mobile teams, there are three shifts: a daytime shift, a swing shift, and a night shift.

“We have a 7am to 5pm and then our second shift comes in at noon until 10 pm so we’ve got about five hours of overlap during the daytime, which actually is looking like our busiest times,” Tappon said. “Our night shift starts at 9:30 pm until 7:30 am. We have a clinician on shift during our day and our swing shift, and a clinician that’s on call for our overnight shifts.”

After the meeting, I asked Tappon what a visit from the Mobile Support Team might look like. (For privacy reasons, I’d made myself scarce during their interview with our housemate.)

While noting that all visits are different and tailored to a person’s unique needs, Tappon said there are some commonalities.

“We tend to start off with asking, how can we help that day or what type of support that person is looking for? That’ll give us an idea of what is happening, or what that person is experiencing, like, what is the nature of the crisis?” she said. “From there, we will ask a series of questions that will be woven into the conversation that we’ll have, like ‘What supports they have right now? Are they connected to family, friends, or other individuals? Do they have services, such as therapy or other types of services that are kind of helping them out? We’ll talk about risk factors—of course, we won’t phrase it that way—but we’ll want to know what challenges are going on for them and what safety issues may be happening. Is this person experiencing any thoughts of self-harm or harm towards others? We want to make sure that everybody we’re coming into contact with is safe and that the people around them are safe.”

“We try and see if we can help stabilize and provide support in that person’s immediate situation,” Tappon said. “If that’s not possible, and if they do need a higher level of care, then we take them to an emergency room or to CSU for further evaluation.”

How is the MST funded?

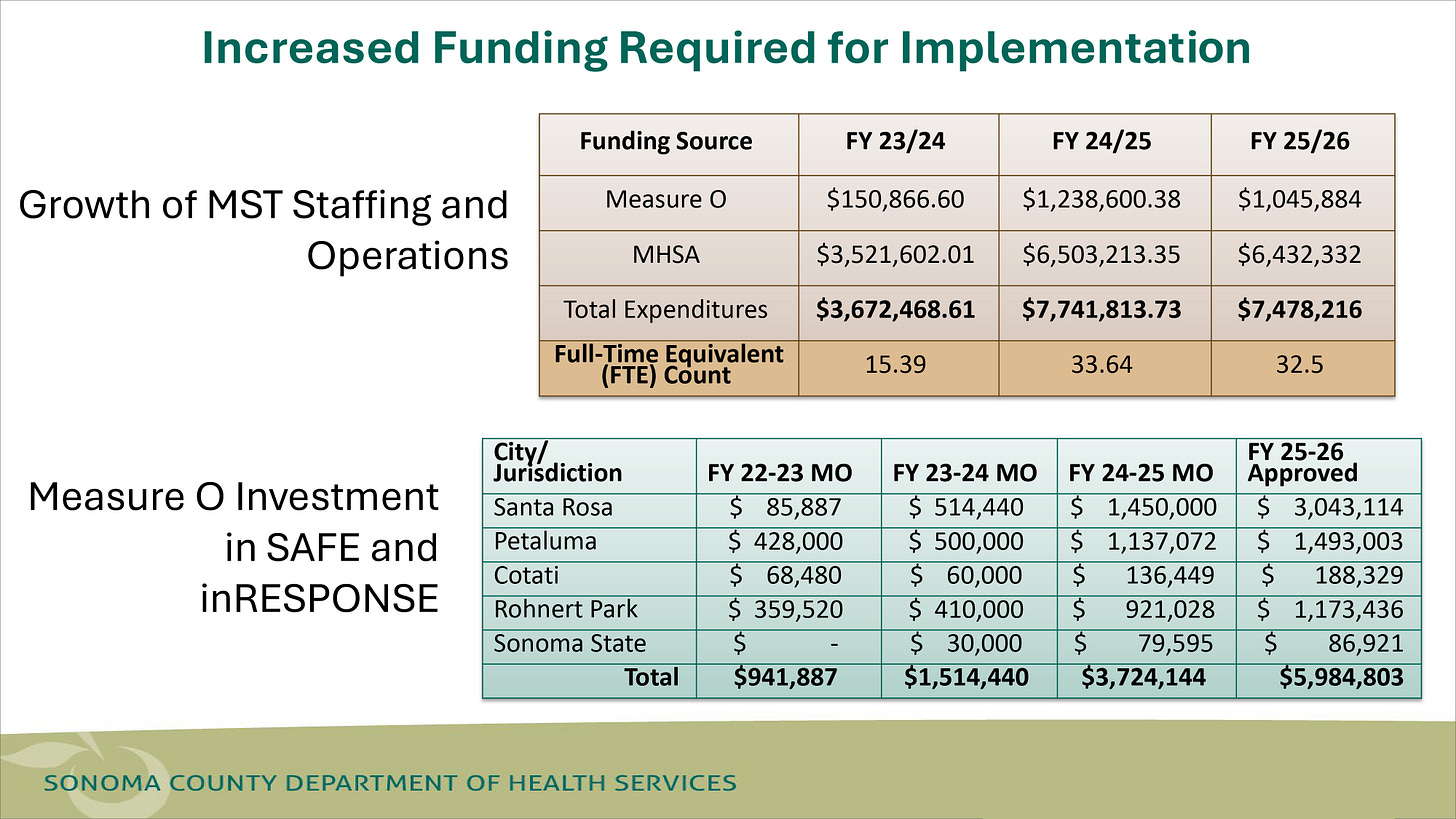

The Mobile Support Team is funded through a combination of state and county money. As you can see in the chart below, the bulk of its funding comes from the state via the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA), which was approved by California voters in November 2004 and is funded through a 1% tax on personal income over $1 million. MST also gets additional funding from Sonoma County’s Measure O, a quarter-cent sales tax that voters approved in 2020 to help with mental health and homelessness.

Additionally, they get some reimbursement for their services through Medi-Cal. “We are only being compensated for Medi-Cal recipients calling for crisis care. So if you’re uninsured or you’ve got Kaiser or some other insurance program, we get $0 to serve you,” Sullivan said.

Dr. Cobaleda-Kegler said they were just beginning to look into how to tap into private insurance.

Interestingly, MST isn’t the only mental health mobile response service in the county. There are two other similar teams: SAFE (which serves Petaluma, Cotati and Rohnert Park) and InReponse, which serves Santa Rosa.

Mayor Zollman asked why there were three agencies doing the same thing, albeit in different areas.

“I think they’re just legacy systems,” said Nolan Sullivan. “I think these systems were developed by police departments in a lot of cases or nonprofits that had a strong investment in those communities. Oftentimes, local governments don’t work very well together.”

Dr. Cobaleda-Kegler said, “So in keeping with the mandate of one crisis hotline number for Sonoma County residents to call, our goal, in parallel, is to unify with our partners into one system that will support all parts of Sonoma County.”

During public comment at the Oct. 7 city council meeting, I stepped out of my press persona briefly to share our experience with the Mobile Support Team and how helpful they’d been in our situation.

So, what happened with our housemate?

You might be wondering why I mentioned poison oak and prednisone when I explained to the Mobile Support Team what was happening with our housemate. It turns out that prednisone, which is commonly prescribed for a host of conditions, has a known side effect—not common but not rare—called prednisone psychosis.

According to a 2020 NIH article, “Steroid-induced psychosis is considered a type of substance-induced psychotic disorder and is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Patients may experience either delusions or hallucinations shortly after beginning a course of steroids.”

The chance of it happening seems to depend on the dosage.

According to that same article, “The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program evaluated 718 hospitalized patients on prednisone and found that 4.6% of patients receiving doses greater than 40 mg/d of prednisone presented with psychiatric symptoms. The incidence rose to 18.4% for patients receiving more than 80 mg/d. A review by Lewis and Smith found similar patterns of increasing incidence with higher doses of prednisone.”

Our housemate, a small, quite slender young woman, took between 40 to 60 mg a day for several weeks. (Oddly, the urgent care doctor she saw didn’t prescribe a dosage—she said she likes to give her patients “agency” about that—but the pharmacist who filled the prescription did.) There is no definitive way, of course, to tell whether prednisone was the cause of our housemate’s illness.

The good news about prednisone psychosis is that it goes away when you stop taking the medication—sometimes immediately, sometimes after several weeks.

After the Mobile Support Team left with our housemate in the back of their car, they took her to a local emergency room, where the doctor who spoke with her determined that she wasn’t a threat to herself or others and sent her home. That was probably an error, but it wasn’t the fault of the Mobile Support Team.

Our housemate’s boyfriend drove her back to our house, but her condition continued to deteriorate. Her mother flew in from out of state, and for one terrible week, our housemate was held at Santa Rosa Behavioral Healthcare Hospital. (They wanted to hold her longer, but her mother prevailed in the court hearing that takes place when an institution wants to hold you longer against your will.) Then she and her mother flew back home.

The good news is, she’s feeling better and restored to herself, but she’s still haunted by this experience. She gave the Sebastopol Times permission to share her story.

Thank you for this informative article on a service I did not know much about in Sebastopol and Sonoma County. The Mobile Support Team info is now in my contact list. You are such a great asset to our community. Thank you!

Very well-written story. It is something many may not be aware of. Thank you for an informative article.