Roundup: Labor Day Special

The Barlow Boys and the Forgotten Holiday

What do you say on Labor Day?

Actually, do you wish people a happy Labor Day? That it sounds awkward points out that it’s kind of an awkward holiday.

In an August 27, 1997 editorial for the Sonoma West Times and News, Barry W. Dugan called Labor Day the “The Forgotten Holiday.” It’s not that people forget to take a holiday but rather they forget the reason for the holiday in the first place. Dugan asks: "Have you ever stopped to think why a national holiday honoring the struggles of the labor movement gets tossed off as just another three-day weekend at the end of summer?”

Dugan wrote about folk-singer and labor activist Utah Phillips, who then would be in the area for a Labor Day event in Occidental. Dugan quoted Phillips, saying:

“You’ve got to keep track of the people you owe. The people who came before me and fought the long and bitter struggles, I owe them and honor them. We are the recipients of their legacy.”

The Barlow Boys

I saved a part of the “Blackberry Mania” story for Labor Day. The Barlow Boys are also part of the Barlow legacy, and we might view them through a different lens than they did at the time.

Thomas E. Barlow needed blackberry pickers. In 1904, he made arrangements with the Boys and Girls Aid Society of San Francisco to bring 50 boys to the ranch as berry pickers. He asked the Society for more boys the next season.

According to a biographical sketch of Thomas Edgar Barlow, written by Tom Gregory in 1911, Barlow was “instrumental in getting boys from the Boys and Girls Aid Society in San Francisco to pick berries during vacations, which gave them a pleasant outing in the country as well as an opportunity to earn money. With the idea of making a pleasant camping place for his young helpers, Mr. Barlow set out a eucalyptus grove, and the camp is now a well-established institution.” After Mr. Barlow’s death in 1904, Mrs Barlow “continued his policy.”

About 100 boys came in June and stayed at the camp until the beginning of September. Here is a photo of some boys from 1910, which adds as caption: “Each child has a full berry box fastened around his neck and is carrying two additional boxes.” The boys were thought to be as young as seven and the work in the summer sun had to be hard. (Berries were cultivated in the U.S, but not in Europe because the brambles made it so hard to pick the fruit.)

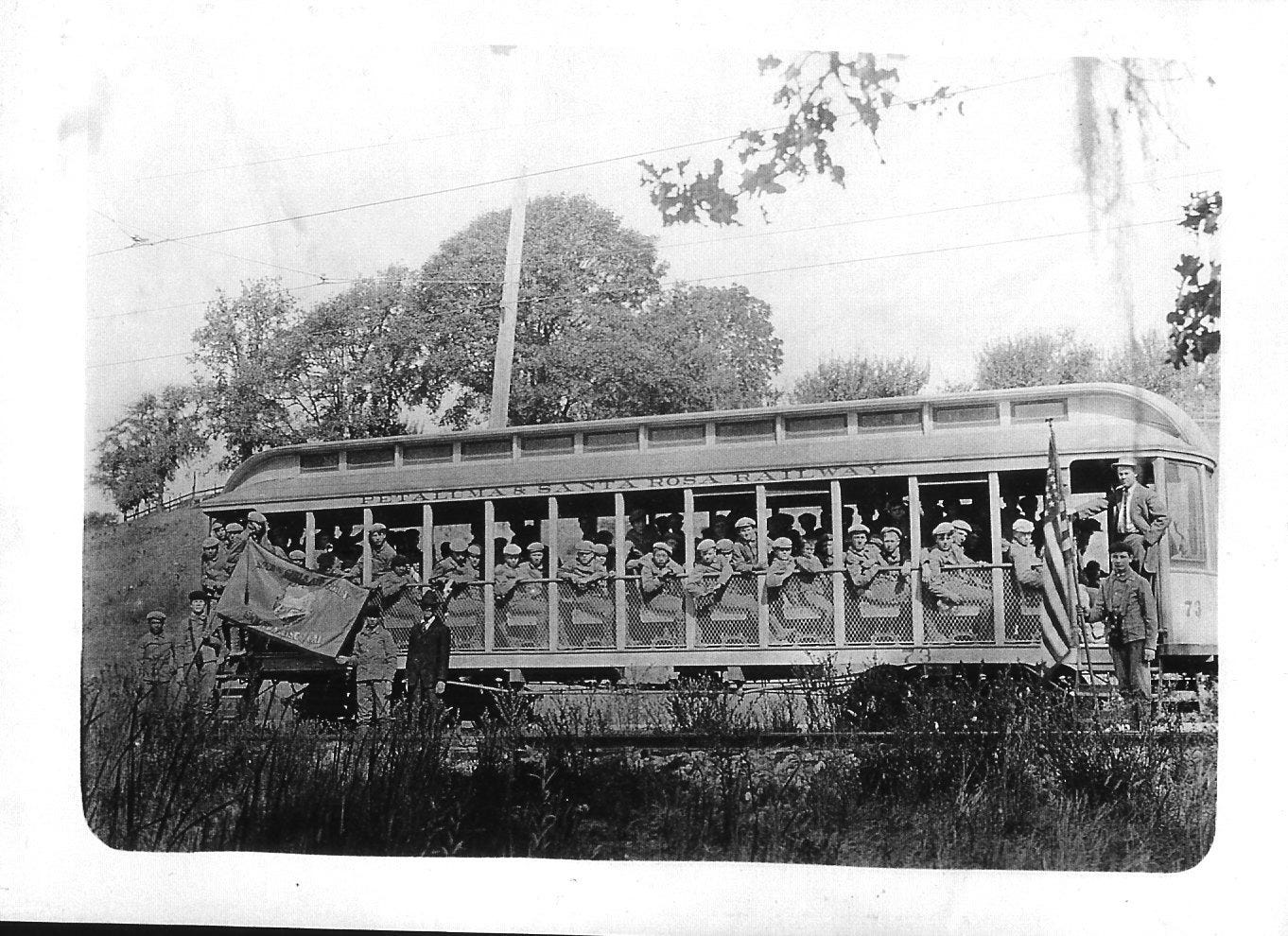

The Barlow Boys came to the ranch by railroad - the Petaluma and Santa Rosa Railway, which went through the Barlow Ranch.

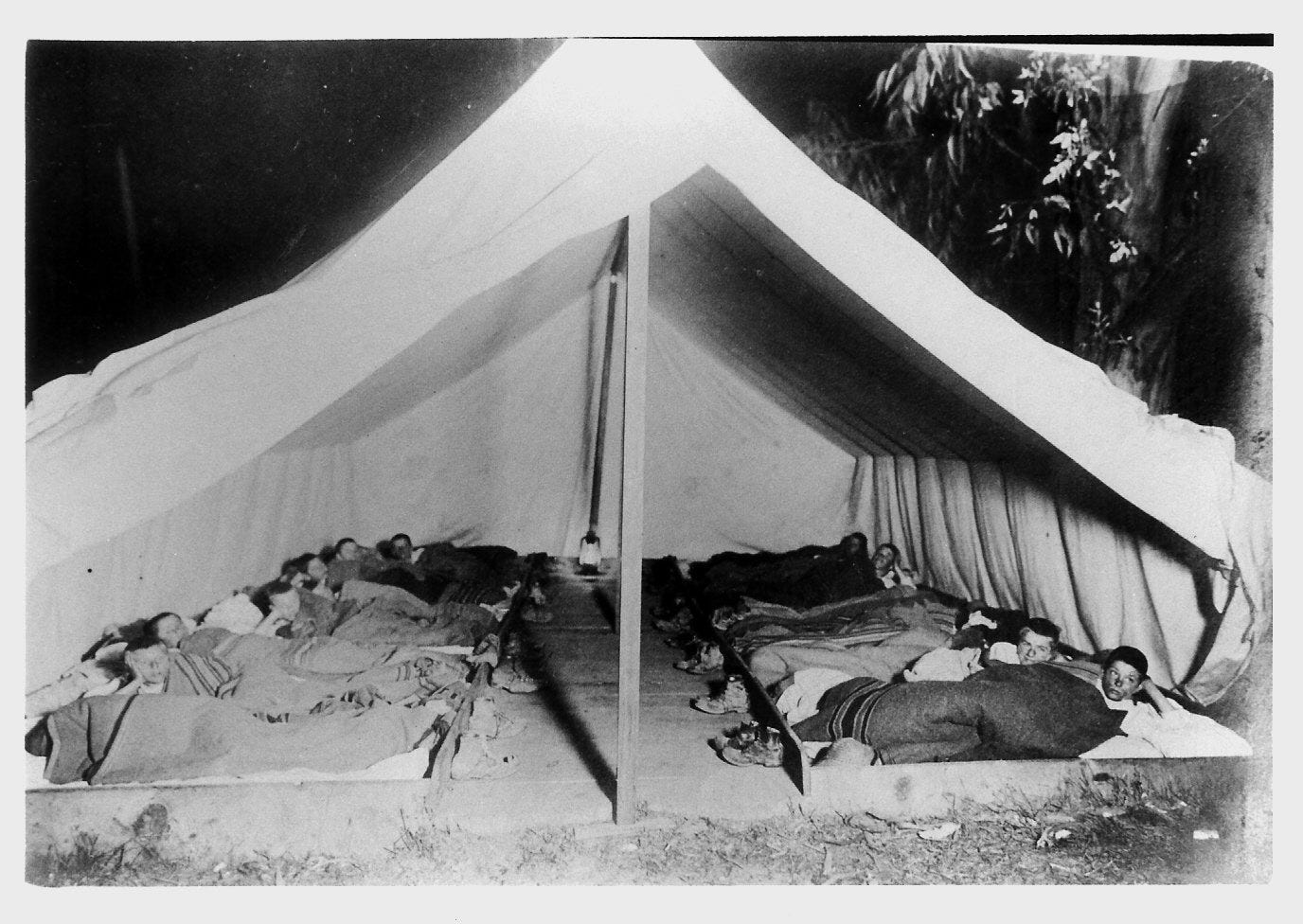

The boys slept dormitory-style in tents at camp.

The Boys and Girls Aid Society of San Francisco in its Annual Report of 1905 says that: “The Society rescues homeless, neglected and abused children,” and also “juvenile offenders.” They provide for these children “until suitable homes, employment and oversight are found for them.” The reports says that “boys may be had for service at wages; for indenture; or for legal adoption.” George C. Perkins was the President of the Society, and the name of the youth camp at Barlow Ranch was called Camp Perkins. The camp was located on their property at the corner of Barlow Lane and Occidental Road, near where Taft Street winery is today.

We can get some sense of the work the boys did, the hours they worked and how much they were paid by this August 17, 1917 article in Sebastopol Times:

“BOY BREAKS BERRY PICKING RECORD - Sidney Cooksley, a 14-year-old berry picker, connected with Camp Perkins on the Barlow Ranch, broke the season’s record of individual picking by picking 74 trays, thus earning $3.33 for a day’s work of 9-1/2 hours.”

That’s about 4.5 cents a tray and about $.35 cents an hour. In 1904, according to the Society’s annual report, the boys earned about $2000 as a group and the money was to split among them to be used to “buy clothing and start a bank account.” An August 11, 1915 edition of Sebastopol Times says that there were 168 boys at the camp, and that the collective amount earned by the boys would be between $4,500-$5,000. (The article’s purpose was to re-assure the community that “this small army of berry pickers” was being fed by “large quantities of food purchased locally.”)

In 1922, the camp had 122 boys and earned $7300 for three-months work. “They picked 260 tons of berries and 60 tons of prunes, besides cutting several tons of pears for the dryers,” said an article in the Sebastopol Times of September 8, 1922 about the Barlow boys breaking camp and returning to San Francisco via a “big excursion car” on the railroad.

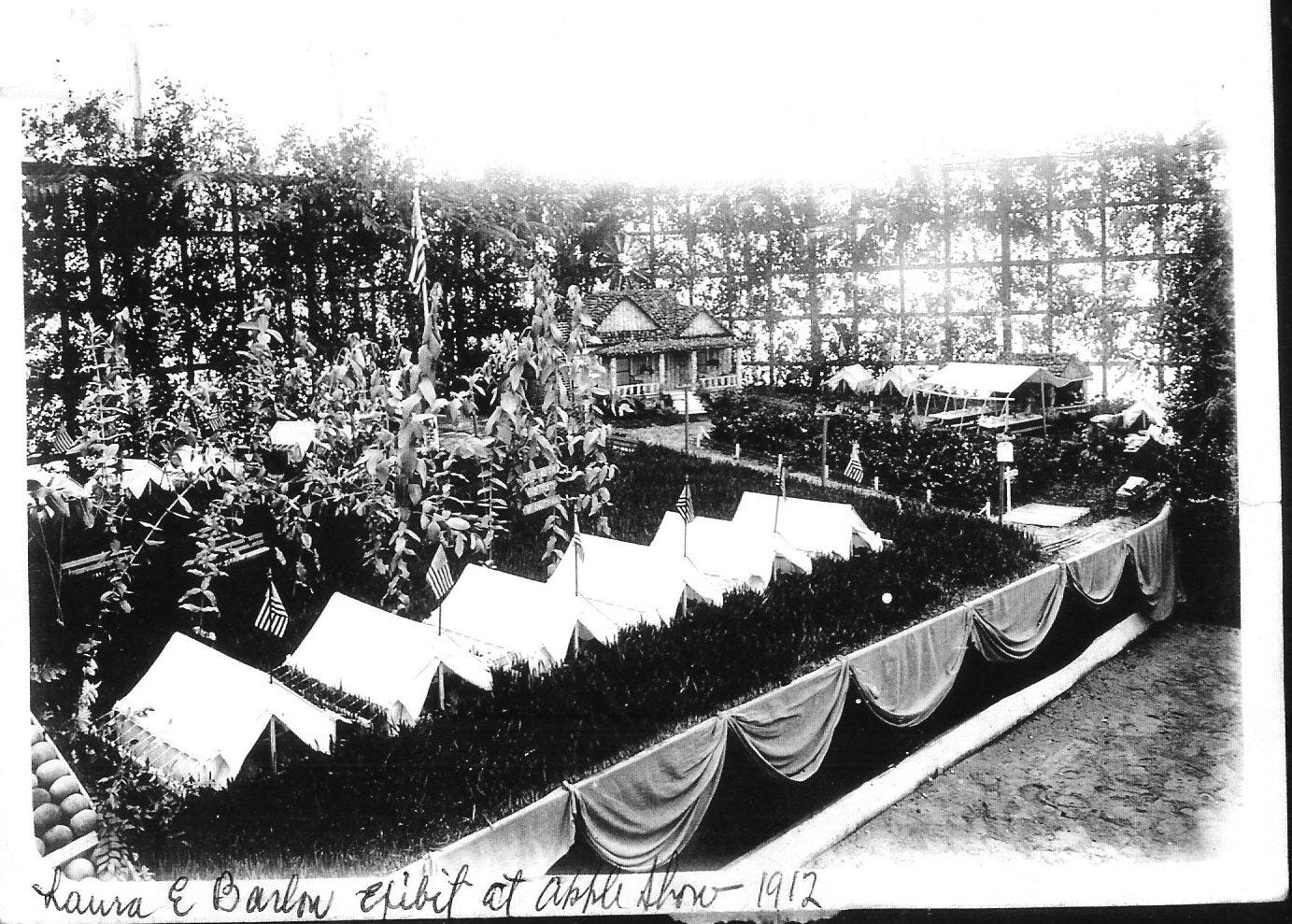

Laura E. Barlow was rather proud of this camp. In 1912, she exhibited a diorama of the camp at the Gravenstein Apple Fair.

Generally, civic pride seemed to color most stories of the annual encampment of the Barlow Boys. Jeff Elliot in his Santa Rosa history presents a different view that not all the boys were happy campers in “The Untold Escapes of the Barlow Boys.”

It was like clockwork: In June the Barlow boys arrived, then a few weeks later came reports of runaways. But after the 1911 season, it appeared the escape attempts stopped. What happened? Boys were still trying to get away, all right – but the Santa Rosa newspapers just stopped reporting about it.

Both Santa Rosa newspapers were enthusiastic about the summer program, says Elliot in “Sebastopol’s Child Labor Camps”

What’s not to like about reading that bad boys were being reformed by spending summers in the country? And their days spent here surely were among the happier childhood memories for the boys, who otherwise would be training at the Aid Society for a lifetime of factory or machine shop work. Then why were they always trying to escape?

He adds that escape from the campground was not easy. At night, their clothes were taken from them and put under lock and key. He adds: “there was a $10 bounty on runaways – the equivalent of almost a week’s wages for the average Santa Rosa household – so the community was always alert for escapees.”

Elliot cites a 1917 state report on farm labor that chose to study Sebastopol because it had more than 400 young urban farm workers in its berry fields. He summarized the report:

The good news was that all of the farmers (except one) thought the boys did good work. But the state also found the food was sometimes “scanty” and the amount of money left to the boys after the living expense deductions was “nil or negligible.” Most damning was this conclusion: “This work is justified only as a means of financing an outing for the youngsters.”

Elliot adds: “To be fair, the Barlows and other growers probably would have been horrified if anyone suggested they were exploiting children or abetting the Aid Society to do same.”

Yet, however we might look at the Barlow Boys differently today, the advocates for child labor laws in the 19th and 20th century were the organized labor groups who also called for a national holiday to recognize workers. They got a federal Labor Day in 1894. Banning child labor took much longer (here’s a timeline).

Whether the Barlow Boys are an example of exploiting children for forced labor or an opportunity for children to be paid for a “pleasant outing” in the country, the story of the Barlow Boys is part of Sebastopol’s past that deserves a place of honor on Labor Day.

Thanks for a terrific, timely snd well-researched story.