Who will live in Gravenstein Commons and how will they be chosen?

Part 2: The good news is that cities can have some say in who ends up in permanent supportive housing in their community. The bad news is that federal funding for homelessness is up in the air

This is Part 2 of a two-part article on Coordinated Entry, the system the county uses to connect homeless individuals with housing. Find Part 1 here.

At the heart of last week’s city council discussion of Coordinated Entry was the question of whether Sebastopol will have any say in who moves into Gravenstein Commons, the permanent supportive housing development currently under construction at 885 Gravenstein Hwy. N.

When Elderberry Commons was populated this spring via the county’s Coordinated Entry system, the city—and this reporter—were told that neither the city nor the county had any say in who could live there. Rather, we were told, placement was purely dependent on a homeless person’s vulnerability score within the Coordinated Entry System.

It turns out, that’s not entirely true.

Hunter Scott is the vice president for HomeFirst, which is the Coordinated Entry System operator for Sonoma County. He said that cities can have some say through the use of what’s known as the “subregional by-names list” — an official list of homeless individuals in a particular area.

He suggested this in his first appearance before the council in August, and Mayor Zollman invited Scott and his team back to give a presentation about Coordinated Entry and the ways (if any) that the city could influence who gets placed at Gravenstein Commons.

After HomeFirst’s presentation (which was outlined in Part 1 of this article), Mayor Zollman went on the offensive, grilling Scott on various points. Strangely, these were points that had just been pretty thoroughly explained in the preceding presentation, but it had been delivered at breakneck speed, and Zollman said he just wanted to make some points clear to the public.

This included that “eligibility for who gets placed in these projects is driven by funding, and that the permanent supportive housing providers are the ones that choose the funding from the very beginning.”

Scott confirmed this. In the case of Gravenstein Commons, the main funder is the state of California’s Homekey+ program, which provided $6.5 million for the construction of the project.

After the council meeting, we reached out to Jack Tibbetts, director of St. Vincent de Paul Sonoma County, which is the developer of Gravenstein Commons. Tibbetts said that in addition to Homekey+, they plan to apply for Measure O funds through the county; HHAP (Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention) from the state; and PLHA (Permanent Local Housing Allocation) also from the county. Once construction is complete, they plan to apply for project-based vouchers from the federal government through HUD (Housing and Urban Development).

It is likely that all of these programs will have something to say about the eligibility criteria for Gravenstein Commons.

At one point during the council meeting, Mayor Zollman suggested that he and Interim City Manager Mary Gourley should have a meeting with Scott and Tibbetts and go over the list of applicants together “to decide whether they would be a fit. What month should we think about having that meeting?”

Scott was clearly taken aback. “It would be unusual for eligibility criteria to get to the point where a city is reviewing individual applicants,” he said. “It’s not impossible. I’m just sort of processing that idea live.”

Zollman asked if Scott was saying that it couldn’t happen.

Scott fell back to, “It’s up to the eligibility criteria” which again is set by the developer in accord with the requirements of their funders.

In response to Zollman’s suggestion of a literally hands-on approach to choosing tenants for Gravenstein Commons, Councilmember Hinton said, “I just want to say I didn’t think it would go to the level of where we’d sit down at a meeting and be reviewing individual HIPAA-based applications,” she said.

Hinton said that the city manager had been in communication with Tibbetts and had already expressed to him the council’s interest in having local applicants for Gravenstein Commons. “That is why I voted for these projects to serve first our community and have a local preference,” she said. “But it was not my expectation that we would be sitting in a room picking the applicants for the project.”

Use of a local “By-Names List”

Scott said there are some housing projects in Sonoma County that set their eligibility criteria to include a “subregional by-names list.” This allows a permanent supportive housing developer to pick, at least partially, from a pool of local homeless people. Scott noted that there is a West County By-Names List with 123 people on it. The problem with that, he said, is that many on that list may not meet the strict federal requirement for chronic homelessness.

According to HomeFirst’s Kaitlin Johnson-Carney, the federal definition of chronic homelessness is “either somebody who has been consistently homeless for the past 12 months straight and they have a verified disability, or they have been consistently homeless for the past three years, but with four breaks that add up, so that their time homeless still adds up to at least 12 months within those three years.” (See Part 1 for an explanation of this tortuous definition.)

Scott also noted that that West County By-Names List could possibly be broken down further to separate Sebastopol from greater west county.

“So those are the things that we kind of have to map out together, and we’re willing to sort of do that openly with you all and with Jack,” Scott said.

The use of a local by-names list is a potentially crucial one for Sebastopol. It could mean that some of Sebastopol’s homeless people—the folks we see on the street every day—could potentially be housed at Gravenstein Commons.

The Sebastopol Times reached out to the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) about the use of a by-names list. We asked if it was legal and if they could give us an example of a project where a by-names list was being used.

We received this answer from Alicia Murillo, a communications specialist with HCD.

For Homekey program compliance, using a subregional prioritization system or by-names list is allowed. HCD defers to local jurisdictions and Continuums of Care to establish prioritization systems for their Homekey units, so long as they are:

housing the appropriate demographic given the Homekey general eligibility and specific target populations called out in the Standard Agreement, if applicable (chronically homeless, youth, veteran, etc.)

using Coordinated Entry or a comparable prioritization system and

abiding by Housing First principles per WIC Section 8255 when it comes to tenant selection. [Editor’s note: The first core component of this is “Tenant screening and selection practices that promote accepting applicants regardless of their sobriety or use of substances, completion of treatment, or participation in services.”]

Murillo continued, “If they were doing something like refusing eligible Coordinated Entry referrals from outside Sebastopol and keeping those units vacant to wait for a Sebastopol resident, that would be an issue. But if they want to prioritize local residents using their by-names list and they are following Sonoma County COC rules, as long as those tenants meet Homekey tenant eligibility requirements.”

As an example of the use of a subregional by-names list, Murillo said, “City of Rohnert Park uses their city’s by-names list for referrals, and they are under the same County Coordinated Entry system as Sebastopol.”

The Elephants in the Room: The government shutdown and the fate of homeless funding under the Trump administration

In his final question, Mayor Zollman asked, “Given what’s going on with the federal government, how is that going to affect permanent supportive housing as a whole and the timing of Gravenstein Commons in particular?”

Scott deferred to Nolan Sullivan, the county’s new director of Health Services.

“There’s been proposals on what to do with HUD since June-ish or so, by the current administration,” Sullian said. “They range from devastating to status quo. The shutdown has exacerbated all of the problems in the time frame…We anticipated that we would have some knowledge of what’s happening through the Transportation, Housing and Urban Development Appropriations Act”—which is, hilariously, called the THUD—“but all that has been delayed and so we don’t know.”

Zollman pressed the point. “So you’re opening permanent supportive housing—dirt’s being dug—but what is happening with the federal government? If they crash and burn everything, is it still going to progress?”

Nolan said he didn’t expect to have any firmer knowledge until the end of October or November. If federal funding for homelessness was drastically reduced or eliminated, he said, “It wouldn’t be like a hiccup or a bump in the road. It would be catastrophic.”

Then Nolan suggested, “I’d put a pause on anything that is strongly federally based for at least two to three months until we actually figure out what’s going to happen. Maybe all this panic is for nothing, and it’s a status quo budget, and nothing actually happens, and it’s all good, but again, we just don’t know yet.”

We reached out to Sebastopol’s Interim City Manager Mary Gourley to find out what the city was thinking about Sullivan’s suggestion of putting a pause on projects (like Gravenstein Commons) until we see how things shake out with the federal government.

“The City was a co-applicant for Project Homekey funding, but we do not manage, own, or operate the project and can’t force a pause on the project,” Gourley responded. “As of today, grading and underground utility work have been temporarily paused due to soil issues. Construction is expected to resume mid-month, with substantial completion now estimated to be delayed by approximately one month. The City expects to receive updated reports from St. Vincent de Paul and the City’s consultant later this week.”

What is the current timeline for Gravenstein Commons?

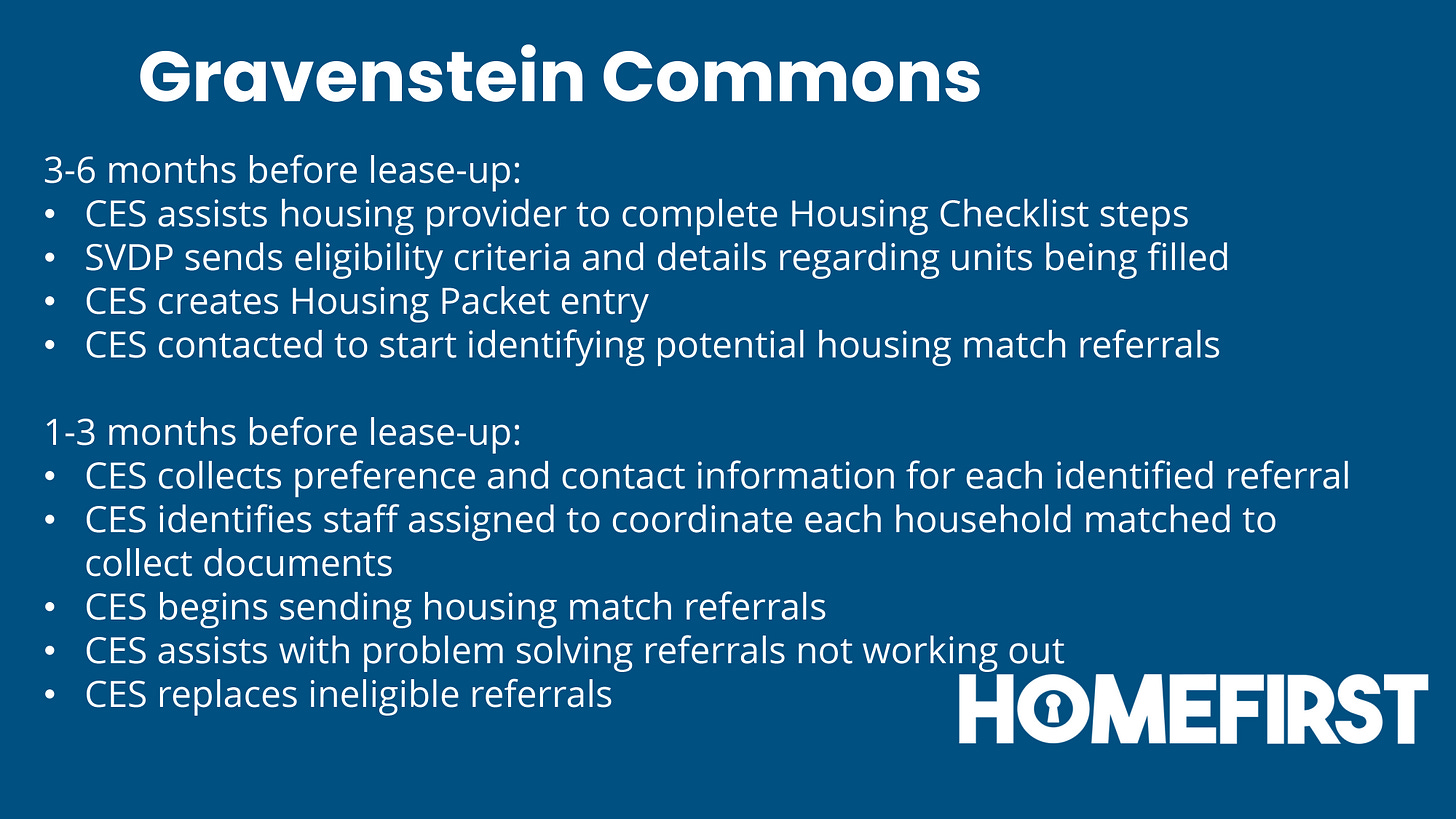

In her presentation at the council meeting, Kaitlin Johnson-Carney, director of Coordinated Entry System (CES) for HomeFirst, revealed one surprising piece of news: Gravenstein Commons is now expected to be move-in ready five months later than Tibbett’s original estimate—in October or November 2026, rather than June 2026. (Admittedly, he said he hates making predictions in a system with so many moving parts.)

Carney also presented Gravenstein Common’s timeline with regards to the Coordinated Entry System (CES):

She drew the council’s attention to the second bullet point, noting that Sebastopol could ask Saint Vincent de Paul to include a Sebastopol subregional by-names list as part of its eligibility criteria, which would allow it to screen for homeless individuals currently living in Sebastopol.

Zollman pressed again about when the city should have meeting with Tibbetts to make sure this happens.

Scott suggested that the city get together with Tibbetts in June of 2026 or perhaps earlier “if Jack solidifies his funding streams earlier.”

Other efforts at improving permanent supportive housing

Scott also gave an intriguing glimpse of how the County is trying to fix permanent supportive housing in ways that could improve the lives of its residents and the experience of communities that host them.

According to Scott, this includes the following:

The first is just coordination of additional layered services, particularly behavioral health services.

The second is that the Homeless Coalition [of which Mayor Zollman is a member] is working on county-wide permanent supportive housing standards that could tackle things like…

What’s the communication plan when these types of sites open in the community?

When is it appropriate to issue a lease violation?

What’s the appropriate level of service of these sites?”

HomeFirst will be providing input into those. I think there’s an opportunity for the city of Sebastopol to do so as well, and I hope that the city actually adopts those rules for sites in your jurisdiction.

Lastly there’s an idea going around with Nolan and DHS staff of taking some of the most vulnerable in our community and routing them into county shelters first with the idea that they could stabilize there before going into permanent supportive housing.

Some of these moves, particularly the last one, are in line with the Trump Administration’s announcement in July that it was ending support for the “Housing First” model of addressing homelessness.

According to that order, which is known as Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets, “The Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development shall take appropriate actions to increase accountability in their provision of, and grants awarded for, homelessness assistance and transitional living programs. These actions shall include, to the extent permitted by law, ending support for “housing first” policies that deprioritize accountability and fail to promote treatment, recovery, and self-sufficiency; increasing competition among grantees through broadening the applicant pool; and holding grantees to higher standards of effectiveness in reducing homelessness and increasing public safety.”

For a while, I thought reading Laura's recaps was just like attending the meetings, but I was wrong. It's better. There is no way I could appreciate the nuances and background to the pointed interactions I'd witness live. Thank you for always presenting the bigger picture.

This complicated process of providing housing for homeless folks in Sebastopol is head-spinning. Thank you for covering it in all it’s minutiae. I am impressed beyond belief at the dedication of those who work through the tangle of requirements to place each person in housing. Many thanks!