Roundup: Leftovers

The farm boy that won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, $3 tamales, and the first Zero Waste Superhero.

This is a weekend for leftovers and finding little things left behind.

The Secrets of Willard F. Libby

Sometimes there are leftovers when you write a story, something that doesn’t quite fit the main story and gets left out. In my September conversation with Steve Fowler about the Luther Burbank Experiment Farm, Steve, a local actor, talked about his roles in the Cemetery Walk for many years. He told me a story about playing Willard Libby, the accomplished nuclear scientist who graduated from Analy High School in 1926. A mural of a rather dour Libby is on the wall of the school library and Libby Park on Valentine Road is named for him.

Of Willard Libby, Steve said “he was a lonely man. And you can imagine why. He couldn't talk to anybody about his work. Even other scientists who were not at his level in the secrecy world. Each level means you have to leave those other folks behind. You can't talk to them anymore. And so he'd gotten to the point where there was no one he could talk to. And his wife? Of course, no way.”

Steve continued: “Libby was depicted in the cemetery talking to his high school science teacher because he'd had a crush on her. She was, of course, just lying there. And, it's a very touching idea. I mean, it's a painful to think how you carry those secrets around. He says it's like lead weights in your pocket, to know things that nobody else knows.” Viewing Libby as a lonely man full of secrets is a good story, but I was curious to learn more about him, especially in light of the Oppenheimer movie.

I found an oral history interview of Willard Libby recorded in 1979 by the American Institute of Physics.1 Willard F. Libby grew up on a Sebastopol farm, went to public schools in California and won the Nobel Prize in 1960 for his work discovering the process of radiocarbon dating. That’s the summary, but here is more of his story.

In 1913, the Libby family moved from Colorado to Sebastopol when Willard was five. His father was a farmer, and the family lived on a ranch that his father managed but did not own. Libby worked summers nailing together wooden crates in an apple processing plant. At Analy High, he was a “B” student and student body president. “I wasn’t a good football player,” he said, “but I was one of the largest players.” Willard was over 6’2”. He was an avid reader, enjoying literature and history. He said that he got a good fundamental education at Analy but his interest in science would come later.

After graduating from Analy, Willard Libby did not go to college but instead took what we now call a “gap year” to work on his family’s farm. Libby called “working as a farm hand one of the wisest things” he ever did. He wasn’t sure what he wanted to do or study in college. “Out of 100 students in my class, only two went to college,” said Libby, although he noted later that many of his classmates went on to become very successful. Libby said that he could have stayed working on the ranch but his father, whose formal schooling ended after third grade, insisted that he go to college after his year was up.

When he went to UC Berkeley, he was able to pay for college with the savings he had from working. He didn’t follow his interest in the humanities because he was uncertain how it would lead to a career. Instead, he chose engineering and then later changed his major to physical chemistry. “There was no place that matched Berkeley in those days for chemistry,” said Libby. The department was run by Gilbert Newton Lewis, whom Libby called “a remarkable genius.” Lewis “was the first one to propose that the stars run off of nuclear reactions,” said Libby. It was Lewis who brought Robert Oppenheimer to Berkeley.

Libby’s research involved radioactivity. “I built the first U.S .Geiger Counter there,” he said. He graduated with a PhD in chemistry in 1933. At the outbreak of World War II, Libby went to Columbia University to work on the Manhattan Project and managed 140 people. After the US dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, Libby is said to have come home with all the day’s newspapers, and told his wife: “This is what I’ve been working on.”

Asked what he remembered most about the Manhattan Project, he mentioned Leslie Groves, the general played by Matt Damon in the movie. He recalled “the incredible ability of Groves to manage. Here's this general officer, an engineering officer, didn't know a bean about science, but the way he could do it. He used the scientists as advisors and he listened to them. But there was nothing democratic about Leslie Groves.” He also recalled “the enormous collection of talent. In my 140 people I had 25 of the leading young chemists working for me.”

Asked if he and other scientists talked about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the time, he replied: “Oh, of course. See, Groves kept the thing so compartmentalized that practically the first thing we knew was the newspaper report.”

After the war, Libby became a professor at the University of Chicago, where he picked up his own research again. He developed the methods for radiocarbon dating based on detecting the half-life of carbon-14. “Libby realized that when plants and animals die they cease to ingest fresh carbon-14, thereby giving any organic compound a built-in nuclear clock.”2 He began with a theory and then had to build equipment that could measure the decay of carbon 14. For proof for the accuracy of his methods, Libby produced a chart, the “Curve of Knowns,” that compared the results of radiocarbon dating of objects against those who date of origin was already known. In 1960, he won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery. Willard Libby’s “introduction of radiocarbon dating had an enormous influence on both archaeology and geology—an impact often referred to as the “radiocarbon revolution.”

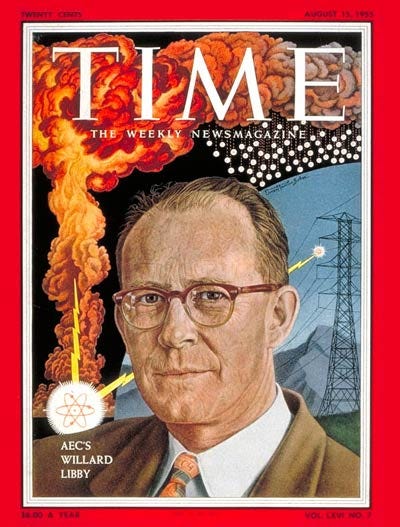

He served as the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and worked on public policy for nuclear energy. In August 1955, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

In 1959, He left the AEC to take a position as professor of chemistry at UCLA and he remained there until he retired in 1976.

Libby was married for 26 years to his first wife, whom he divorced in 1966 to marry Leona Woods Marshall. A PhD chemist, Leona Woods also worked on the Manhattan Project during the war in Enrico Fermi’s Chicago lab. “She worked on the team that constructed the first nuclear chain reaction leading to the development of the bomb” and she was the only woman on the team of 42 scientists.3. She joined Libby at UCLA becoming a visiting professor of environmental studies and engineering. Willard Libby died in 1980, a year or so after the oral history interview, and Leona died in 1986.

He once remarked: “There's only one way to keep a secret and that is, don't repeat it.”

$3 Tamales

If you’re looking for a break from turkey leftovers, try the tamales at a food truck in front of El Favorito on Main Street. They come highly recommended from regular contributor Mark Fernquest.

“I eat there at least once a week and relish every bite. They offer up to a dozen different types of tamales, some sweet. Chicken mole, red chicken, green chicken, red pork, green pork, bean and cheese, and more. My favorite is the chicken mole. All cost $3 each. Choice of red or green salsa side or an extra hot orange sauce that is really good. Their big sign was taken down but their menu now says you can pay with some kind of cash app. They tend to sell out by noon-1, so get there by 11 or they may be gone.”

Mark added that the owner doesn’t speak much English. “I also have a great time brushing up on my Spanish with the owner and her children.”

Zero Waste Superheroes

Let no leftover go unrecycled.

The Zero Waste Group of Sebastopol's Climate Action Committee has a new program called Zero Waste Superheroes. The first awardee is Lauralee Aho, who lives at Burbank Heights and Orchards, Sebastopol's low-income senior community.

"She is coordinator of the residents’ group, a prime mover in all art-related activities and involved in almost everything happening at Burbank Heights and Orchards," said Judith Morgan, a fellow resident and editor of the community's newsletter. "One of her greatest contributions is managing our Zero Waste Shed. We have had the Zero Waste Shed for close to two years. Lauralee personally takes most of the recyclables to be recycled. Residents bring many kinds of recyclables to the shed. They are collected in the shed and then properly recycled...The Zero Waste shed has greatly reduced what is sent to the landfill from Burbank Heights and Orchards. In large part, this is because of Lauralee."

“Recycling is just the right thing to do," Aho said. "Fortunately we make money from some of the items we recycle. Kudos go to all our community members who pitch in with their items.”

Do you know of a zero waste superhero? Send your suggestion to Ambrosia Thomson at AThomson@recology.com.

Week of November 20-25

Larry Robinson’s photograph of the Laguna along with his selected poem for Thanksgiving was popular, receiving 14 likes.

Installation of CCTV cameras riles library staff

Two weeks ago Sonoma County Library Director Erika Thibault called a special meeting of the staff at the Sebastopol Library to announce that CCTV cameras would soon be installed on the outside of the building.

Poetry in an age of ecological crisis

It’s a busy time for Graton writer Elizabeth Herron. As Sonoma County’s Poet Laureate for the 2022-24 term, literary events, local functions and her signature ‘Being Brave’ classes keep her schedule full. “Being poet laureate for me is an act of service; it’s a way of giving back, and it’s a way of expanding the role of poetry in our lives,” she said.

A Thanksgiving Poem

I’m thankful for so many things this morning. I’m thankful that I don’t live in a war zone. I’m thankful for the amazing place that we do live—its beauty is a gift every day. I’m thankful for my home and my family and friends. And I’m thankful for our ma…

Council rejects parcel tax, but declares financial emergency

A council majority made up of Mayor Neysa Hinton, Vice Mayor Diana Rich and Councilmember Stephen Zollman voted to approve “a declaration of a fiscal emergency.”

Footnotes for The Secrets of Willard F. Libby

Interview of Willard Libby by Greg Marlowe on 1979 April 16, Niels Bohr Library & Archives, American Institute of Physics, College Park, MD USA, www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/oral-histories/4743-2

Wikipedia, Willard Libby.

Women in History profile, Leona Woods Libby.

That was a fascinating story on Libby. Thank you for the Footnotes for The Secrets of Willard F. Libby

Thank you for the back-story on Willard Libby! I’ve always wondered about these details.